Review

Laying These Ghosts to Rest

A Call for Reproductive Justice

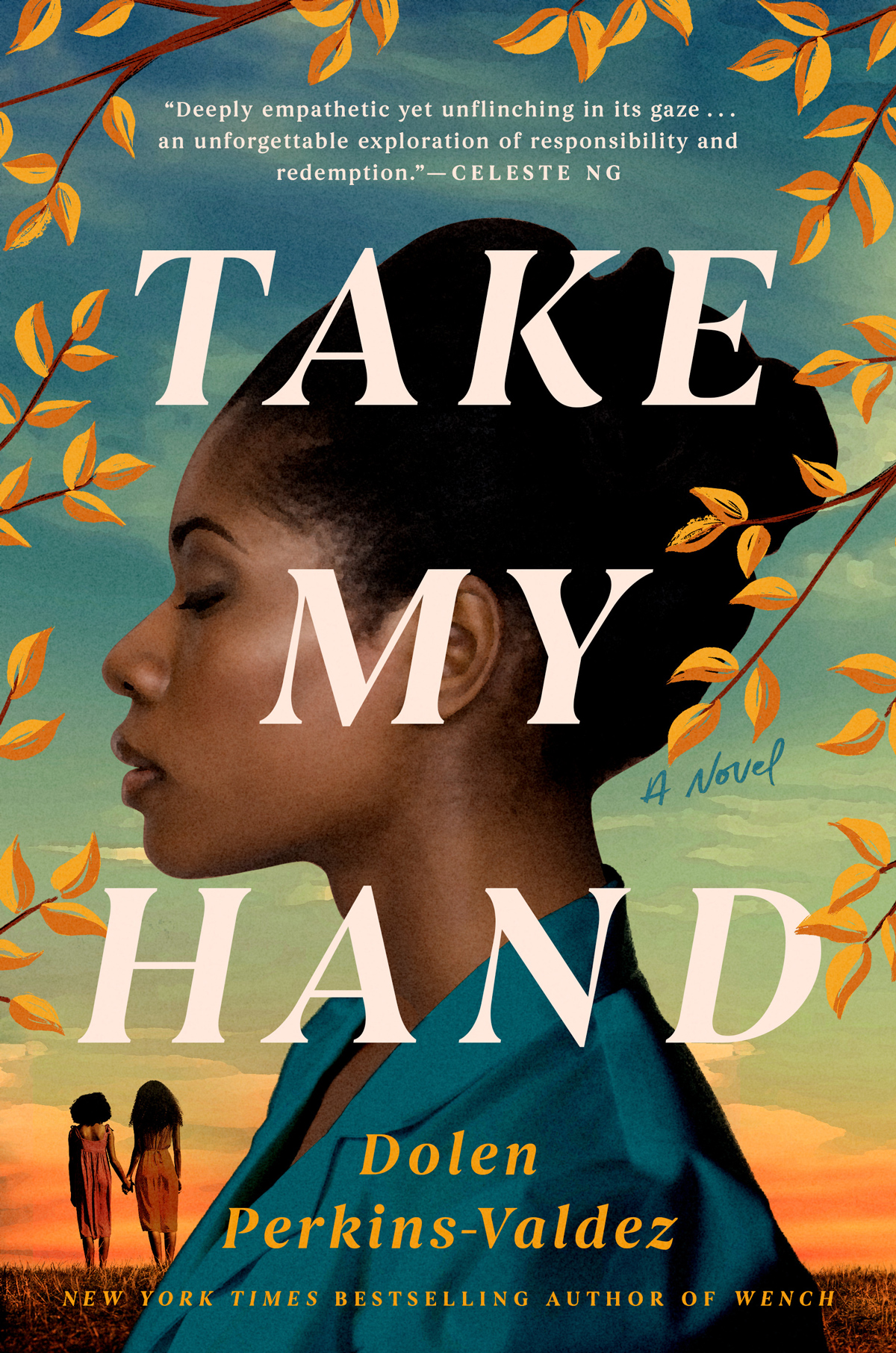

Take My Hand, A Novel

by Dolen Perkins-Valdez

359 pp. Berkley, Penguin Random House

By Dr. Brenda M. Greene

Dolen Perkins-Valdez, a bestselling author, has written a narrative inspired by the real-life case of the Relf sisters, the young Black girls (Mary Alice, 14, and Minnie, 12) who were forcibly sterilized in 1963 in Montgomery, Alabama. The author of Wench (Amistad Harper Collins, 2010), Perkins-Valdez, writes historical fiction that uncovers deep truths about the history of Black people in this country. Whereas Wench focuses on the moral complications of slavery, Take My Hand expands on this theme by focusing on the violation of the Black body. Civil Townsend, a nurse and the narrator in Take My Hand, recounts the story of a heart-wrenching tragedy that highlights the racial and health disparities experienced by Black women and women of color across our nation.

Erica and India, just eleven and thirteen years old, represent the Relf sisters. Forty-three years after the incident, Townsend is still disturbed by it and vows, as written in the quotation above, to tell this story to her adopted daughter so that she can “lay the ghosts to rest.”

Perkins-Valdez conducted extensive research for this novel and found that thousands of girls and young women of color participating in government-sponsored family health clinics were subjected to sterilization practices that did not adhere to federally approved guidelines. There was no accountability or monitoring of the actions of those in leadership positions in these clinics. Basic principles of ethics were regularly violated.

Participants were not informed, had few or no advocates, and could not read consent forms and information on the experimental nature of drugs, studies, and procedures given to them. A class action lawsuit filed by a lawyer and the Southern Poverty Law Center on behalf of the Relf sisters exposed widespread sterilization abuse. As many as 100,000 to 150,000 poor people were sterilized under federally-funded programs; many were forced to agree to be sterilized to maintain welfare benefits.

The facts emanating from this devastating abuse of two young girls and the revelation of its widespread occurrence bring to mind the violation of women’s bodies from the time of enslavement, a premise based on the fallacy that Black women’s bodies are different than White women and as a consequence, Black women have a high pain tolerance.

The recognition and honoring of doctors who performed these inhumane procedures to further gynecological research are etched in our nation’s history. Confederate statues depicting doctors who abused enslaved women came to life at the height of the Black Lives Matter Movement when activists lobbied to remove statues in remembrance of those individuals who exploited enslaved peoples. Kentucky doctor Ephraim McDowell, considered a hero, has a bronze statue in the United States Capital Visitor’s Center dedicated to him. Known as the “father of abdominal surgery,” he built his research on using enslaved women to develop a surgical treatment for ovarian cancer. J. Marion Sims, a 19th-century gynecologist, known as “the father of gynecology,” conducted experimental surgery on enslaved Black women. After protests emerged, a statue of Sims in Central Park was removed.

As we know, experimental procedures on poor women and young girls were not restricted to women. The Tuskegee Study on untreated syphilis in Black men impacted a group of nearly 400 Black men. Perkins-Valdez covers this study’s origins and harmful effects in her novel. The long-term effects of this experiment (a 40- year, non-therapeutic experiment on the effects of untreated syphilis in Black men in the rural South) are still affecting Black men and women. One major result is a fundamental distrust of the healthcare system.

Dolen Perkins-Valdez,

from Take My Hand, A Novel

Erica and India, young, poor young Black girls in Perkins-Valdez’s novel, underwent forced sterilization at the height of compulsory or forced sterilization, also known as coerced sterilization, in this country. They had a loving grandmother and father, but their caretakers could not read. When social workers came to the home, they listened to what they were told and accepted at face value what they were told about the drugs and “check-ups” their young girls needed. They signed their names with an “X” and trusted a system that violated their basic rights. They lived in poverty and were at the mercy of a failed public health system for people with little resources.

As their visiting nurse, Townsend tried to protect the girls and organized with other nurses to prevent them from enduring harmful drugs and procedures; she was devastated when she discovered what had happened to India and Erica. Her attempt to ensure this did not happen to other poor Black, Hispanic and Mexican women succeeded when she worked with the family on a lawsuit; however, her acts did not “lay the ghosts to rest.” The lawsuit required doctors to obtain “informed consent” before performing sterilization procedures, but Townsend lived with the horror of what the girls encountered for decades.

The Civil Rights Movement provides a context for the novel. When Townsend and the family travel to Washington DC to testify at the lawsuit, they meet United States Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who, in the novel, was the leading attorney in the suit. Townsend’s southern middle-class family attends the church where The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was pastor. Her father is a doctor, and her mother is an artist. She has options for college and initially chooses to become a nurse instead of a doctor because she wants to have direct contact with her patients. These factors contribute to her choice to “take a hand” in addressing the inequity suffered by these young girls.

Although the story is centered on Townsend’s determination to stop Erica and India’s abuse and provide them with a healthy and safe environment, Perkins-Valdez weaves in other themes that intersect to illustrate the complexity of reproductive health for Black women. These themes include the intersection of class, privilege, public policy, disability, and the overriding theme of the need for love.

Townsend’s distant relationship with her mother points to her need for intimacy and to serve as a mother figure to India and Erica. She longs for the “love” she does not receive from her mother, who is preoccupied with her painting and lives in her own sheltered world. In reflecting on her relationship with her mother and father, she states, “I might have been a daddy’s girl, but it was not by choice. I had always longed for a mama who read to me at night and kissed me before school in the morning.” The late bell hooks, a feminist writer, reminds us of the need for love in her book, All About Love: New Visions. She states, “A generous heart is always open, always ready to receive our going and coming. Amid such love, we need never fear abandonment. This is the most precious gift true love offers—the experience of knowing we always belong.” It is apparent that Townsend, in caring for the girls, was responding to her feelings of abandonment and her need for love.

Perkins-Valdez’s novel is particularly timely. We are now at a crossroads. The Roe v. Wade decision in 1973 provided poor women of color with options and slowed down the push for forced sterilization. Women could take control of their bodies and opt to have abortions in a safe environment. Now that the US Supreme Court has overturned Roe v. Wade, women once again find that they have limited control over their bodies. The courts have determined that the state, not the individual, decides whether a pregnancy can be terminated.

This is a complicated moral issue for some. Despite the varying views, the issue of how to provide women with alternative options for the termination of an unwanted or harmful pregnancy is no longer a right of women. This is medical discrimination and a call for reproductive justice.

Take My Hand reminds us that although we continually face complicated moral issues, we are responsible for offering care to each other. If we practiced taking the hands of those less fortunate than us and the victims of medical discrimination, racism, housing inequality, sexual abuse, education, and so forth, we would contribute to addressing some of the social inequities in our communities. This novel has a strong message for our community.

View an interview with Dr. Brenda M. Greene and Dolen Perkins-Valdez at https://youtu.be/JvufSOVWfwg