By Mary Alice Miller

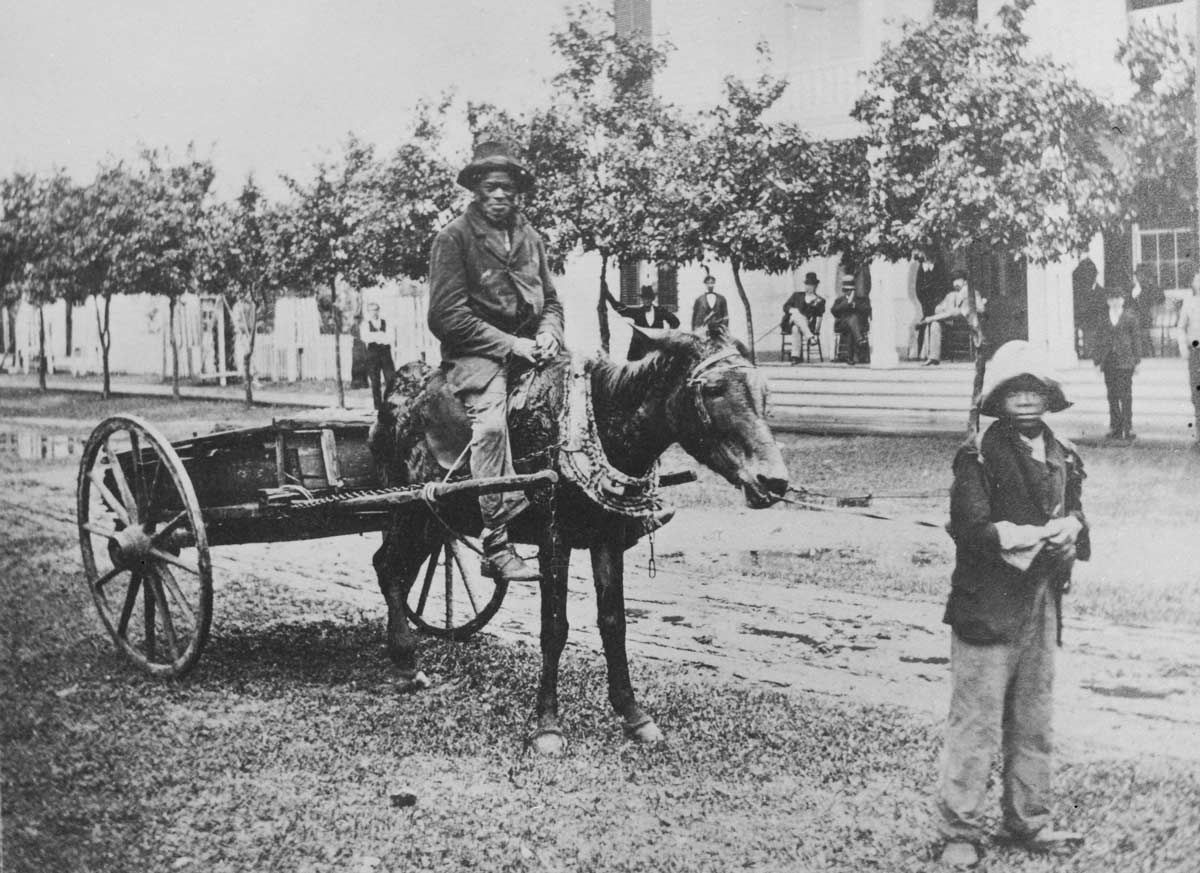

Most Black Americans have heard that after the Civil War, former chattel slaves were promised 40 acres and a mule, this country’s first attempt at reparations. As far as we knew, none ever received the land. It was yet another among a long line of broken promises to make good on 244 years of the brutal chattel slavery system.

New research from the Center for Public Integrity has found that upwards of 1,200 or more former chattel slaves did receive acreage, which was promptly taken away. Hundreds of titles for specific plots of land between 4 and 40 acres in size were uncovered and found among more than one million Freedman’s Bureau records.

Freedmen and women built houses on the land, farmed it, and established local governments.

After President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, his successor, President Andrew Johnson, stripped the property from those formerly enslaved people and returned it to their former slave owners.

Investigators at the Center for Public Integrity conducted research for two and a half years and identified 1,250 Black men and women who had been granted land as reparations after the Civil War.

On January 16, 1865, Union General William T. Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15, an edict that set aside coastal land in South Carolina, Georgia, and northeastern Florida for former enslaved men and women to work, live on, and govern themselves. A group of Savannah, Georgia Black ministers persuaded Sherman to issue the edict.

The land pledge from Sherman would become known as “40 Acres and a Mule.” The Freedmen and women were not promised a mule, although some did receive one.

Sherman’s Special Edict stated that the islands and coastland of Georgia, South Carolina, and northeastern Florida were to be for exclusive “settlement of the negroes now made free by the acts of war.” It granted the head of each family up to 40 acres of land on seized or abandoned plantations. It gave them military protection “until such time as they can protect themselves, or until Congress shall regulate their title.”

Further, the Special Edict stated that “in the settlements hereafter to be established, no white person whatever, unless military officers and soldiers detailed for duty, will be permitted to reside; and the sole and exclusive management of affairs will be left to the freed people themselves.”

Sherman later explained in his memoirs that he had not necessarily intended that the Freedman and women had rights to the land indefinitely, but at least through the end of the war and until federal officials took more permanent measures.

During the early Spring of 1865, President Abraham Lincoln hedged against the broad reach of Sherman’s edict when he signed into law a bill stating that Black families could rent their chosen plot of land for three years, with the option to buy them. That same bill created the Freedman’s Bureau, an agency charged with coordinating services – temporary housing, food, healthcare, education, and work – for the 3 million formerly enslaved people residing in the United States.

Lincoln’s first vice president (1861-1865) was abolitionist Hannibal Hamlin, who advocated for the arming of Black Americans. Andrew Johnson, a known drunk and senator from a Confederate state (Tennessee), was elected Lincoln’s second vice president. Both Lincoln and Johnson supported national unity and the return of seceded states to the Union, but Johnson did not favor federal protection for freed former enslaved people.

One month after Lincoln signed the bill creating the Freedman’s Bureau, he was assassinated.

As president, Johnson opposed the 14th Amendment that gave newly emancipated freedmen and women citizenship rights and believed Black suffrage should be addressed under States’ Rights. He supported the Southern Black Codes, which bound freedmen to work on their former plantations and subjected them to arrest for loitering and vagrancy, with renting out their labor as punishment.

Johnson vetoed the Congressional extension of the Freedman’s Bureau and every Congressional bill that sought to treat formerly enslaved people fairly, including the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the First Reconstruction Act. Congress systematically overrode almost all of Johnson’s vetoes. Johnson’s efforts to circumvent Congress’s intent to address the rights of Freedmen and the position of former Confederate states led to 11 Articles of Impeachment against him, which Johnson survived in the Senate by one vote.

By June of that year, about 40,000 Black people had settled on land set aside for them under Sherman’s edict. A year and a half later, almost all the land had been taken back.

The land titles were first discovered in 2021, part of records created by the now defunct U.S. Bureau of Refugees, Freedman, and Abandoned Lands. These records were digitized within the last ten years, an effort that resulted from the Freedmen’s Bureau Preservation Act passed by Congress in 2000.

The initial discovery of land titles was found in a digitized roll of microfilm labeled “Unbound Miscellaneous Records.”

The discovered land titles covered over 24,000 acres on 34 plantations seized by the Union Army from Confederate landowners, just part of the land holdings distributed under Sherman.

Some of these land titles have been known to exist among the National Archives paper records since 1991, and one has been featured on the National Archives website since 2007.

The paper records led historian Karen Cook Bell to write “Claiming Freedom: Race, Kinship, and Land in Nineteenth-Century Georgia” (2018), in which Cook Bell identified nearly 400 formerly enslaved men and women who had received land titles in Georgia.

The Center for Public Integrity used the land titles to conduct genealogical research to find what happened to the descendants of the 1,250 Freedmen and women in the one-and-a-half centuries since Sherman’s edict. Of those who could be placed in about 100 family trees, 41 living descendants were found.

It should come as a surprise to no one that the lands titled to Freedmen and women, then taken away, are now developed into affluent communities owned by white people.