Black History

New York City’s Infamous Civil War Draft Riots

by Suzanne Spellen

There is nothing more frightening than a mob, nothing more uncontrollable than a riot. And there is nothing more deadly than being the innocent person or group deemed to be the target of a mob’s anger. People die and die horribly. This fact was found during the events that took place in July of 1863 in what is now known as the New York Draft Riots, the worst riots in the history of this country.

The causes of the riots were much more complex than just racism and hatred; the reasons for taking to the streets were more than just the unfairness of the draft. They culminate in many social, political, and economic factors, coming together like a perfect storm at that time and place. Like all acts of terrorism, the riots brought out the worst of humanity and the best of it. Here, in a nutshell, is what happened in New York City between July 13th and July 16th of 1863.

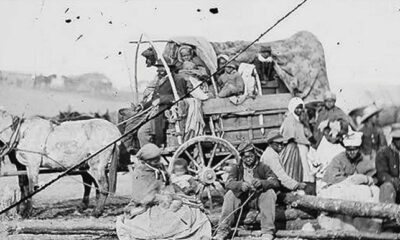

New York in the 1860s was a city of contrasts. Slavery was finally abolished in New York in 1827, the next to the last northern state to do so. (NJ was the last.) But 30-some years later, that didn’t mean the African-Americans in NY were now equal to whites in the city. Most black people in both Manhattan and Brooklyn were manual laborers and in service – digging ditches, hauling cargo at the docks, washing clothing, being maids or cooks, all performing the lowest-paid jobs that could be had in the city, with few opportunities to do better.

The Abolitionist movement was growing in popularity among many New Yorkers and Brooklynites due to the fiery preaching of Brooklyn’s Rev. Henry Ward Beecher and others, and the tales of slavery’s horrors by men and women such as Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and Sojourner Truth. People of goodwill and conscience wanted to end the ownership of one person by another and free those enslaved on the plantations and cities of the South. After that, they weren’t too clear about what to do next, and most gave little thought to the freemen and women already in their midst.

And there was another disconnect. By the 1860s, the economy of New York City was inextricably tied to the fortunes of the South and, thereby, to slavery. The cotton produced by slave labor in the South came north to be processed, sold, and manufactured into goods, then shipped across the country and overseas. Each step in that process made someone in NYC rich. The city’s banks, insurance companies, shipping companies, and even producers of paper and other goods sold down south were all making a fortune on the products of slavery.

Banks gave loans to southern planters with enslaved people as collateral, and Wall St. traded based on formulas of the productivity of slave labor. Some of these capitalists made noises about how much they hated slavery and how evil it was. Still, the more honest also said that that same evil kept the money flowing, which was a tragic but necessary consequence of business. New York has always run on the needs of industry.

If that wasn’t conflicted enough, add the immigrants. By 1855, census reports show that roughly two out of every three adult Manhattanites had been born outside the country, and over half of the city’s population came from somewhere else. Most of the immigrants at this time were from Ireland and Germany. Many German immigrants who came here in the 1850s fled that nation’s attempt to unite separate city-states and the resulting political unrest. Despite the greater language barrier, they were, on the whole, more middle class, better educated and skilled, and fit into established and successful German communities in both Manhattan and Brooklyn.

In contrast, most of the Irish were a different story. The Potato Famine in Ireland began in 1845 and didn’t end until 1852. The primarily Catholic Irish were serfs to an oppressive Protestant English aristocracy that had worsened the famine. Over a million Irish somehow made it to America during that time with the promise of a better life.

For most of those who landed in Manhattan, it was a lie. This predominantly peasant class had no skills, no education, many did not speak English, and no chance to rise out of the horrific slums they were crowded into. They lived in places like 5 Points, which even today is remembered as the worst slum in the city’s history. The unskilled Irish immigrants suffered great discrimination by native-born Americans and were treated no better than black folks in many ways. Signs saying “No blacks, no Irish allowed” were not rare.

For many poor Irish and German newcomers to this land, the Civil War was just one more disappointment to be found in this new country. No longer starving in the fields and villages of rural Ireland or political pawns in the German states, many of these immigrants were now living hand to mouth in the slums and tenements of the worst part of Manhattan, an overcrowded cesspool of filth, crime, and misery. One of the few consolations in a city where the native-born and better-off treated them like they weren’t human was that there was one group they could safely feel superior to, New York’s black population, many of whom were living in similar situations.

For these people, the Civil War was the war to free the enslaved, something they had no interest in fighting for. It wasn’t just simple racism, although it certainly was that; it was also survival. The feeding frenzy at the bottom of the economic food chain pitted the black population against the white immigrant population, both groups fighting for menial and unskilled labor jobs.

Free-born black citizens, emancipated ex-slaves, and runaways all walked the city streets. Many employers thought nothing of using them as strikebreakers or lower bidders for jobs that the new immigrants needed. Employers would often play one group off against the other, the result being that whoever would accept the lower wage would get the job.

Two groups that could have united to bring about labor reform were united only in hate and fear. What should have brought the two groups together, a shared sense of survival and the camaraderie of oppression, instead became hatred and intense competition for the bottom rung of the economic ladder. The newly empowered Democratic Party played into those fears with incendiary literature, characterizing the black workers as lackeys of the wealthy establishment and inferior and uncivilized savages, both enemies of the white workingman.

When the Civil War started in 1861, the general sentiment was that this was a war to bring the southern states back into the Union and repair the country. When the Union Army defeated Robert E. Lee’s Confederates at the Battle of Antietam, Maryland, in 1862, Abraham Lincoln thought this would be the opportune time to issue his Emancipation Proclamation. He believed that the combination of a decisive Southern defeat and the freeing of the slaves would propel the Northern forces into a more significant effort to defeat the Confederacy, restore the Union, and win a great moral victory.

For New York, that strategy was a disaster. The War was no longer a struggle to preserve the Union, but now it was directly a call to end slavery. The merchants and bankers whose fortunes depended on slavery were now being called to end it. The immigrants being drafted to fight were called to increase the freedom of a group of inferior people they felt were already stealing jobs from white men. Now they were supposed to fight to free more of them?

As the Civil War dragged on, volunteers became fewer and fewer, and heavy casualties and desertion were taking their toll. The National Conscription Act of 1863 was enacted to fill the ranks with able-bodied (white) men. The final insult and catalyst for the riots was the rule instituted in that Act that allowed a $300 buyout of the draft, which essentially exempted anyone wealthy enough to pay. Three hundred dollars was almost half a year’s pay for an unskilled working man. The rationale behind this buyout was that those vital to society would be spared, such as captains of industry and their sons and brothers.

This totally backfired, as it was immediately seen for what it was – a way for the rich to ensure that the poor would do their fighting for them. This was going to be a poor man’s army sent to fight and die for the benefit of even more inferior blacks, who would no doubt flood into New York and the North, taking what few jobs were available away from these same fighters. Meanwhile, the rich would go on as they always had, above it all. It was unthinkable and was not going to happen. The Draft was the last straw.

The Battle of Gettysburg, the bloodiest battle of the Civil War, ended on July 3, 1863. Over 8,000 men on both sides were killed, with almost 29,000 wounded and 12,000 captured or missing. The first lottery of the new draft was held on Friday, July 11th. People were restless and angry, and trouble broke out in Buffalo, NY, but nothing happened in NYC. That weekend plans were made for the next step.

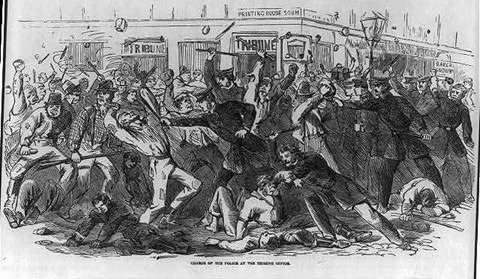

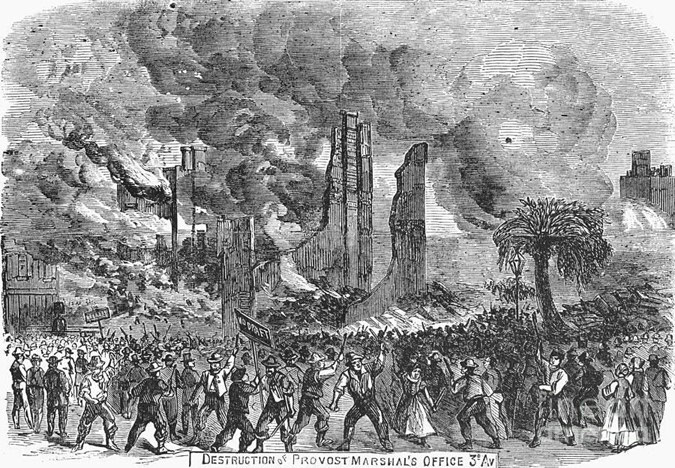

Two days later, on Monday, July 13th, the second lottery was called. Within hours, a mob of 500 men attacked the Provost Office on 47th and 3rd Avenue, where the lottery took place, breaking windows and doors and eventually setting fire to the building. The police were outnumbered and unable to stop the crowds of mostly working-class Irishmen, along with their women and children, who streamed through the city from the docks, building sites, and streets, ready to take on both those above them and those below.

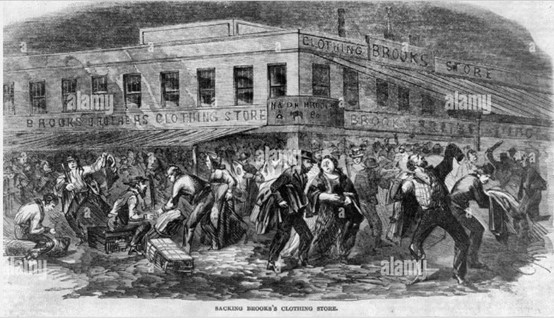

The primary targets were the city elites and their institutions, which had ignored their poverty while exploiting their labor. They raided the Mayor’s house, looting it and breaking windows, burned down the Postmaster’s house, and destroyed churches. The mob went through the streets looking for Republicans and rich people. Rioters targeted anyone who looked well-off. There were shouts of “There goes a $300 man!” in reference to those who could afford to buy out of the draft or “Down with rich men.” The mob attacked and burned Brooks Brothers, the hated purveyor of rich men’s clothing and a manufacturer of Union uniforms. They beat up and killed policemen and soldiers as representatives of the Republican authorities. They looted and burned mansions on tony Fifth Avenue.

When the Superintendent of Police, John A. Kennedy, reached the riots, he was recognized and beaten within an inch of his life. Colonel Henry O’Brien of the 11th New York Regiment was stripped, beaten, tortured, and shot in the head after he fired his howitzer into a crowd, accidentally killing a woman and child. By the second day, the mob headed towards Wall Street, intent on destroying it, but Wall St. was the most fortified part of the city. Behind the police and militia barricades, the Customs House workers made bombs, and the workers at the Bank Note Company prepared vats of sulfuric acid to pour on rioters, if necessary.

Frustrated and growing even more out of hand, the rioters turned to the other objects of their anger and hatred: black people, the living symbols of a war they hated, the jobs they didn’t have, and the freedom of a people who were even lower than they were in the eyes of society.

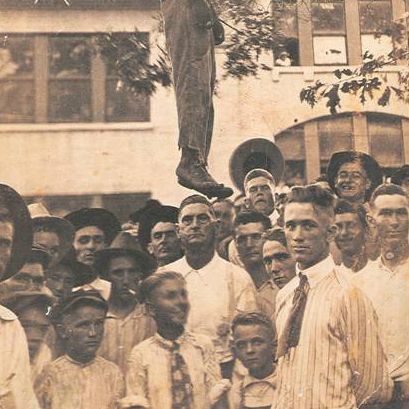

From the very beginning, bands of dock workers and other laborers began chasing African-Americans, screaming, “Kill all n—–s!” Random black people were attacked and killed, most horribly. Whenever any black man tried to defend himself, the enraged mob usually killed him, usually by lynching and then burning the corpse. This happened on several occasions, each more horrific than the last. The mob chased men, women, and children down and attacked any building or institution that catered to or aided African-Americans in any form. They went after bars, boardinghouses, tenements, dance halls, churches, stores, and even orphanages. On the first day of the riot, the mob attacked the Colored Orphan Asylum on 5th Avenue and 43rd Street, screaming, “Burn the n—–r’s nest.” The Asylum was seen as a hated example of the rich white establishment’s favoritism towards the Negro, as the home was large, well built, and well stocked with food and provisions for the children and was in the middle of the city. No such institution was established for them!

As the mob of several thousand men and women attacked the building with bats and clubs, the matron and superintendent managed to herd the kids onto the street. The mob poured into the building, taking blankets, food, and other provisions, and then burned the building to the ground. It only took twenty minutes. Miraculously, no one laid a hand on the children, most of whom were under twelve.

One of the Irishmen in the crowd cried, “If there is a man among you, with a heart within him, come and help these poor children.” The mob turned on him and tore him to pieces. The children made their way to the nearby police station and stayed there for almost three days before being ferried to the Almshouse on Blackwell’s Island. While on shore, the mobs pushed African-Americans to the docks and into the East and Hudson rivers, drowning them.

Like the Irishman who tried to save the children, the mob had a special hatred for whites whom they felt were sympathetic to black causes. They burned the houses of known abolitionists and those businesses that took black trade. On the docks, which were a special sore point to the rioters, as many black men were dockworkers, stevedores, and porters, gangs of men destroyed taverns and businesses that catered to black workers. Even white prostitutes who accepted black men were singled out, stripped, and beaten.

Yet there were also instances of interracial cooperation and bravery. When the mob came after black drug store owner Philip White, his Irish neighbors drove the mob away because White had always extended them credit in his store. While the mob was busy burning the orphanage, a crying, lost black child was wrapped in a blanket by a white man, who carried the child through the crowd like a piece of merchandise and delivered him to safety.

The police were totally overwhelmed and outnumbered. The militias had been called, but most men had been sent to Pennsylvania to deal with the aftermath of Gettysburg and the Confederate advances toward the state capital. Three days had passed when the National Guard was able to get into the city, sent in by the Secretary of War. The soldiers quickly restored order by opening fire on the mobs, killing anyone who resisted. Over 6,000 troops patrolled the city.

In the end, eleven black men had been lynched and burned. Many other black men and women were beaten, drowned, and otherwise killed; the numbers remain unknown. Over 100 rioters were killed, mainly by the soldiers and police, and over $2.5 million in property damages were assessed. Even today, piecing together everything known about the riots, the death toll ranges from the hundreds to almost a thousand.

So, what happened just across the river in Brooklyn? Not much. The Brooklyn Eagle and other daily papers carried detailed descriptions of the violence, which sent readers to either hide in their cellars or go out and join the rioters, depending on one’s proclivities. But Brooklyn remained quiet. Anyone who wanted to go to Manhattan and join in had to be particularly dedicated. This was Brooklyn before any of the bridges were built. The only way to get to Manhattan was to take the ferry.

Among those taking that ferry was the Brooklyn police force and their leader, Inspector John S. Folk. He and his men left their city to aid Manhattan, believing that Brooklyn would remain quiet and safe. He was correct. The only major damage to the city was the burning of two grain storage elevators. This event seemed to be tied to the riots only by circumstances allowing the perpetrators to get away with it.

Brooklyn’s finest hour came in the rescue and shelter of thousands of African-Americans who fled Manhattan, some to never, ever return. They came to Williamsburg, where they were sheltered and protected by the German immigrant community, who put many up in the Turn Verein athletic and social clubs of Williamsburg and Bushwick. Many more made their way to Weeksville, Brooklyn’s independent black town, where they were also sheltered and protected.

For a time, Weeksville was also in a state of heightened tension as reports came in describing a mob of rioters from Jamaica, Queens, who were on their way to Brooklyn to attack. In response, the white citizens of the surrounding area organized to keep order, swearing in extra deputy sheriffs to help protect the community. The mob never came, although they did heavy damage in Queens.

At the end of the riots, New York City would never be the same again. As in the modern-day aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, in the Gulf, the city lost a significant number of black residents, many of whom never returned to Manhattan. Many stayed in Brooklyn; others left the state altogether. It would take years for the black population to rise again. Positions such as dock workers and stevedores would never again be predominantly filled by black workers; the rioters had succeeded in changing the face of the waterfront workforce for good.

Yet, some great good came of the riots, too. They forced New York’s elite to realize that they couldn’t continue to ignore the conditions of the poor, and an age of social reform was begun. New tenement laws were passed in 1867, aimed at lessening the overcrowding and misery, the first baby steps in a long housing reform process. Committees were convened into the causes of the riots, and the city’s rich and elite began to concern themselves with charity and charitable organizations. The great Victorian age of charity would begin here.

The riots caused the rise of the Democratic Party as the political representative of the common working man. Tammany Hall, which had been quite active in inciting the violence, actively sought out Irish and other immigrant groups, signing the men up as voting Democrats. (While also lining their own pockets, of course.) This would result in over 20 years of Tammany control of city government, and as payback, conditions for the Irish Democrats improved. Jobs were created, and the Irish began to move up the economic ladder, just in time for new waves of poor Jewish and Italian immigrants to pour in and assume the bottom rung.

For black New Yorkers, things changed as well. The Republican Union League Club championed the uplift of the colored race. Working with the Committee of Merchants for the Relief of Colored People, they donated funds to help black people find new homes and jobs. They were the sponsors of the first Negro Regiment from New York and proudly marched with the black regiment to the docks as it went to war in 1864. This cemented the Republican commitment to the Negro cause in a powerful public statement. In Brooklyn, most of the charitable elite were Republicans and members of Brooklyn’s own Union League Club. The Party of Lincoln, for many years, was the black man’s friend and ally.

Yet all this symbolic unity would end with the war as New York settled back into its familiar ways of business and profit. The races would still compete for jobs. Mistrust and often hatred were never irradicated. Millions of new immigrants to our shores would bring even more people to compete for the bottom. Still, in the meantime, a small but growing black middle class was quietly rising in towns like Weeksville and racially mixed enclaves in both Manhattan and Brooklyn. It was even more possible for African-Americans to become doctors, lawyers, teachers, and other professionals, have successful businesses, and live where they chose to live. The long slow fight for equality was just beginning.

Sources for these articles are The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, the NY Times, Brookynology, the blog of the Brooklyn Public Library, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City by Leslie M. Harris, “The Cause and Effects of the NY Draft Riots” by Alex Blankfein, and Wikipedia.