Biography

Professor William Henry Mackey, Jr., African Renaissance Man & Griot of Our Time

by Bernice Elizabeth Green*

(*Originally published February 1997 in Our Time Press.)

We expected our first interview with Professor William Mackey, Jr. to last 45 minutes, centering around the history scholar’s take on the differences – if any – between storytelling and the study of history. A few minutes into our session, Professor Mackey detoured into a What-Time-It-Is reality check (for our benefit) with lessons in Mackey’s Basic Economics, Basic Math, and Social Studies. It’s the same thing he does for the community, with his free lectures on Thursday evenings in the basement of 850 St. Marks Avenue in Brooklyn. Four hours passed, and we had not even cracked the surface of our planned exploration of the man and his missions. When traveling with Professor Mackey, there’s no telling what you will find, whom you will meet, or how long the journey will take. On the way, you pick up some fundamental lessons in “Black Survival for an African Future.” It’s part of a life-course Mackey believes everyone in the village has prerequisites from birth. It’s a course Mackey still takes himself.

Mackey’s journeys have taken him to several worlds. In the community, he is known for his scholarship and skills as an educator. In the literary world, he is respected for his writings and his scholarship: he is a linguist (five languages), but he speaks “only Ebonics in public”; he has an assortment of degrees–one is in the science of structural engineering.

In a 1970’s nationwide poll, he was voted one of the top ten photojournalists in the world. Mackey’s poignant images of the Black Experience appear in the critically acclaimed “Eye of Conscience,” a tribute to these acclaimed photographers.

A musicologist whose huge record library includes Big Band to Beethoven, Mozart to Miles, Mackey sings, too. He founded — are you ready for this? — “The Fernandina Florida Gospelaires” and sang lead. His tenor solos rocked Jacksonville, Florida’s famous Bethel Baptist Institutional Church, where he created its popular Glee Club. Music was a staple–along with poetry, drama, jazz, and good eats — of Les Deux Megots, the cafe he owned on East 7th Street in Greenwich Village during the Beat Generation era.

Mackey’s cozy spaces — he owned several–were frequented by artists, poets, dancers, off-Broadway, and out-of-work actors and actresses. Harold Cruse managed Megots for him, and James Baldwin, Moses Gunn, Robert Earl Jones—father of James, Frances Foster, Robert Hooks, Graham Brown, Ted Jones, and many other greats in the arts hung out and performed there. Amiri Baraka was a regular and recited his poetry over what is now called an “open mic.”

Mackey is a contributing editor to the Encyclopedia of Black America (The Negro Almanac) and, as well, to the Pictorial History of Black America, in which some of his photographs appear. His incisive introduction to Barnes & Noble’s 1995 edition of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” is a first. The book has been in print since 1852, and “this is the first time an African American has contributed a critical analysis of the work,” Mackey reveals.

On this year’s Literary Desk Calendar, you can find writer Mackey’s loving tribute to the legendary Langston Hughes. The 1998 Literary Calendar will feature Mackey’s panegyric to Baldwin. Mackey has never gotten over the death of his good friend. And he is trying to come to terms with the recent passing of the great Dr. Edward Scobie.

On average, Mackey walks from Crown Heights across the Brooklyn Bridge to Manhattan twice a week. He sometimes stops in lower Manhattan to teach at DC 37. Courses include The History of Black Music; Race, Ethnocentricity, and Linguistics; African History and Culture. On other days, he travels past Wall Street on foot another 40 blocks or so uptown to Empire State College. There, he unscrambles minds on World History, U.S. Labor, and Black History issues. For Mackey, 77, life truly is about journeys: preparing for them, having the right mindset, starting them, and completing them. He’s concerned that some people do not know how to get to first base. The key to his mission lies: “to open up minds.”

“I’m here to show you how to think; I’m not here to just teach,” he tells his “family” of students in his “Correcting the Mis-Education Series” class at 850. But educate he does with refreshingly honest and irreverent diagnoses of an unwell world “gone crazy.” This evening, Mackey discusses “The Role of Race and Ethnocentrism in Cultural Linguistics (Speaking in Tongues).” He is in control. He was leading his discussion like a conductor – music or train. Yet, the griot-patriarch seeks guidance, too — to convey his message and carry his followers into various worlds of knowledge.

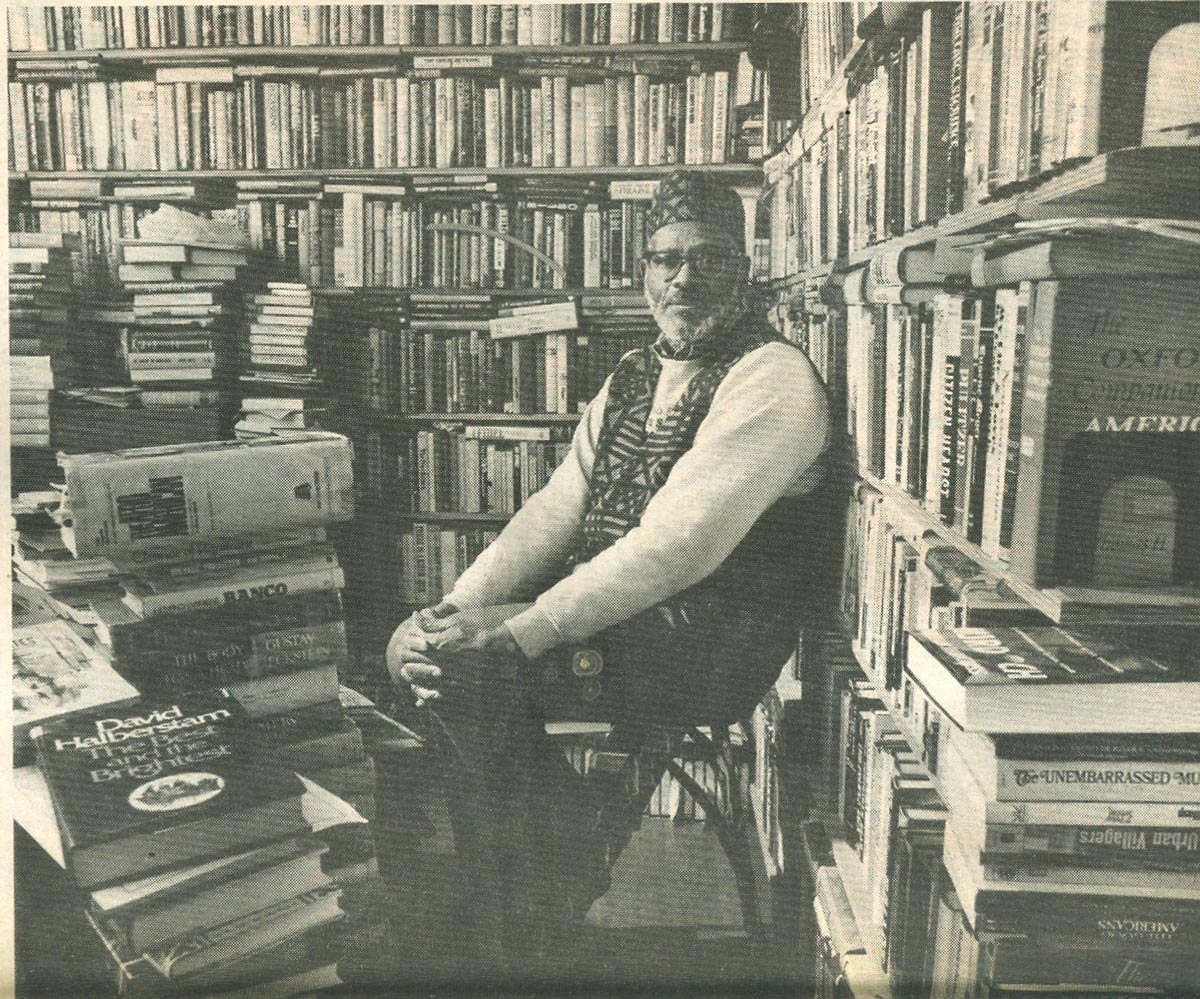

Before each Thursday class, he meditates alone in his apartment tower, surrounded by spectacular pyramids of books, cassettes, and audiotapes. Buried under one heap is an upright, still in-tune piano waiting for Mackey to play it again. The books are so pristine and new-looking; you wonder if Mackey inhales the knowledge without touching the pages. And more books in the dining room, on the windowsill, in Barnes & Noble shopping bags–in every inch of space, except a couple of necessary paths. And more books: all stamped carefully with the Mackey imprimatur and waiting for their place on the shelves of a library Mackey will build in Georgia as a memorial to his grandmother, Harriet Weston.

Mackey takes the results of his reflections downstairs to his Mack-free classes. These are Multi-Afrikan Culturally Kemetic free classes where Mackey’s occasional socially incorrect locutions are in a comfort zone with his readings from word-and-thought-masters he respects, including Dr. John Henrik Clarke, Malcolm X, Howard Zinn, Shakespeare, Mrs. Weston. As many as 35 students on various Thursdays are held captive by the professor’s iconoclastic humor, down-home wit, and idol-smashing curve balls.

Laughter drowns the whooshing of the washers and dryers across from the community room. Mackey is shooting holes in the media’s Main Story of the Week, analyzing them from a fact perspective. He draws parallels between the Ollie North/Crack thing and England/Opium Wars cover-ups. He interweaves history with real-world happenings and makes it sound like poetry. He is a consummate storyteller, and he draws us in. He causes us to make mental notes to check out the Britannicas on our bookshelf, and get into this Global History, a feat which eluded our past – as he calls them — “so-called educators.” I am learning.

“The education system has a long history of dehumanizing people,” Mackey says. “The truth is not being put out there. It’s a continuing struggle trying to steer away from misdirection and miseducation. It’s so easy to delude ourselves into thinking that what we are being told is what it is. Positive insanity is the only rational outlet. I believe we can do it ourselves and learn everything we need to know right in the village. It’s not a new way of thinking. But I would never tell you what to think. I will advise you not to compartmentalize anything. Everything ties in. Knowledge is all around; if you use all your senses, you’ll find it.”

On winter break, a young SUNY college student is listening to Mackey with cautious attention. The class is a release from the madness on her upstate campus, where white students have smeared racist graffiti on the walls and dormitory doors. The following week, the young woman brings her mother to meet Mackey. The mother expresses gratitude, informing him that her daughter is returning to school with a new resolve and some tangibles–newspaper clips, tapes, and book lists from Mackey’s class to share with the other Black students. “My daughter says she met the smartest people here in your class.” Mackey’s mindful assistant professor, Gloria, overhears and promises to ask Mackey if he would establish workshops for young people.

Class readings are pulled from the newspapers each week and distributed to each participant. Before the end of the session, Beverly provides the class with impactful information on happenings outside and within the village. This night, she announces the existence of job openings in the transit system. Mackey immediately calls on transit worker R. to give a summation or “translation” of the real deal. R. strides up in full uniform and offers a read-between-the-lines commentary. He’s brilliant in his way. Yet, T. B., a truly sweet man, interrupts. “Are you talkin’ Ebonics, man?” Elder Mackey cuts a laser eye in T-Bear’s direction. The class is heedful. T-Bear downshifts. R. continues without a missed beat. We’re all learning.

Mackey believes everyone in the village is special. It’s a sentiment his maternal grandma bestowed upon him. The elder Harriet (Sibley) Weston, born in slavery in 1854, decided she would raise her grandson because he was “a special child.” In those days, he says, children didn’t question their mothers. It didn’t matter whether the mother was grown, a teacher, and had good sense. This aptly describes Mrs. Blanche Mackey when her mother took her two-year-old son from Jacksonville, Fla., to raise on her 50- acre farm in the Black village of Scarlett, Georgia, in Camden County. Bill learned the sorts of pastoral things illuminating life and carrying one through it. Under his grandmother’s conscious eye, he learned how to grow corn, rice, and yams… just as she grew him and taught him the value of simplicity and sustenance in a complicated and unsustaining world. (Mackey’s family never sold their land in the South.) Mackey read every book there was to read in Scarlett, and when he ran out of books (most rural Black schools were like the two-room dwelling Mackey attended — 10 years behind without a library to speak of), he would pick from the books discarded as trash by less-poor white schools. (The same way he retrieves pennies dropped from worn pockets and loose purses, now.) Young Mackey treasured these finds. He would dust them off and store their precious shards of knowledge in his photographic memory.

When he completed the highest grade — because of Jim Crow, back in the ’20s and ’30s in the South, the highest grade a Black child could reach was the 6th or 8th grade, if you were lucky– Bill Mackey, by then, a teenage bibliophile, returned to his parent’s home in the big town of Jacksonville to continue his education. Summers, he spent in Scarlett. It was during one of those vacations that Bill, at age 14, taught his grandmother to read and write. Mrs. Weston was in her 90’s. Back then, people “had more pride, more dignity and a sense of history,” he told a reporter in 1985. “They maintained a respect for education that was awesome.” But racism has always been on a head-on collision course with the ancestors’ love for education and their children’s pursuit of it. In one of the nation’s largest cities, Black students had no access to the main library in the’30s. And Bill had run out of books to read in the smaller, poorer Black libraries.

In 1936, Mrs. Clara White, an ombudsman for the Black community, a friend of Mary McLeod Bethune, and one of Jacksonville’s first Black social workers — spearheaded a campaign to open the city’s main library to Black children. (In most Southern towns, Black people in towns like Columbus, Ga.– like Dr. John Henrik Clarke — had to go in through the back door, Mackey says.)

“A library card to us,” says Mackey, “was like a credit card, a passport. That’s how valuable it was then.”

Mrs. White, Blanche Mackey, and other sympathizers and activists went the distance and won a small victory. Mackey could visit the library on Thursdays between 12 noon and 3 pm. Only on Thursdays.

To this day, the professor believes that “one chapter, paragraph, or sentence can make a book worthwhile.” The value of Mackey’s life work will never be overestimated. It is a treasure entitled Down Home: Return to the Georgia Backwoods. This 550-page study of Black life in the lower coastal Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida is both a voluminous work of research culled from 3,000 hours of interviews and 6,000 photographs that combine with his remembrances. It venerates the land tilled and hoed by the ancestors’ hands and shows how “we have taken the garbage and refuse of Western society (and mixed it with the ancestors’ sweat and blood –this writer’s comment) and made it art.”

Mackey is very much concerned about waste. We are wasting minds, wasting time. We were nervous the morning of the scheduled first interview. Twenty minutes late and fumbling with the audiotape, “This stuff oughtta been done on the way here,” he barks. “And now you sittin’ here doing yaw preliminary preliminaries. Thank God we haven’t taken over this morning.”

After the interview, Mackey sets out to walk us to the IND station at the Kingston-Throop stop. After all, he must pick up his copy of The New York Slimes, as he calls it — he reads it daily! — and The Daily Challenge. He’s grumbling about how he’s lost pennies on account of us. It seems folks drop them on their way to work in the morning. And don’t place any value in them enough to stop and pick them up. He’s concerned about us keeping warm. I enter the subway at the Uptown side to meet the train that will take us one stop to Utica. There, I can catch the express running downtown to our stop. (This is Mackey’s idea.)

In the underground, I am introduced to regal Sofronia, the token booth collector who dispenses the coins as deftly as she offers information on the upcoming photo and fine arts exhibitions throughout Brooklyn and New York. We are learning.

Mackey says he will see me soon. Entering the train, I realize I haven’t reached first base in my interview. There is so much.

Two lecture sessions half-dozen ego-smashing phone calls later, I am still trying to pass Mackey’s “course.” But, all the while, I am learning some basic survival lessons: the importance of “going home” to detoxify the mind and unlearn the culture-crushing software “that’s programmed in all of us.” I also have rediscovered the value of a found copper penny.

“It’s a 100% profit,” says Mackey. “Absolutely! A found penny is a 100% profit!” Like the seeds of wisdom Mackey’s students are amassing in those free Thursday night lectures.

In his classes, we’re learning and walking through histories. Listening. Absorbing. I am catching up. Collecting sense. “It’s about time!” Mackey would say.