Black History

First Black Astronaut and America’s Secret Outer-Space Spy Program

Major Robert Lawrence was trained by the Air Force in an elite Cold War-era program. This is why you’ve never heard of him.

Mark R. Whittington

Photo courtesy NASA

On December 8, 1967, a specially modified F-104 Starfighter rolled down the runway at Edwards Air Force Base in California. The weather was cool and crisp, around 50 degrees. The wind speed was eight miles an hour from the south-southwest, and visibility was 20 miles. The mid-afternoon weather, in short, was perfect for flying.

According to an account by former NBC News reporter Jim Oberg, Major John Royer piloted the fighter, which had been modified to fly like a rocket plane such as the X-15. Royer was being taught a new landing technique by Major Robert Lawrence, age 32, who flew as copilot in the rear seat. Lawrence, an African-American Air Force pilot with 2,500 hours of flight experience, had helped develop the novel maneuver, called “flaring,” which involved bringing up the nose of the aircraft as it made a final approach to the runway. The technique would enable the pilot to decrease speed quickly before touch down, an important consideration for a vehicle that might one day return from low Earth orbit.

As the F-104 taxied along the runway, Lawrence was at the pinnacle of his profession: a test pilot and, since June, an Air Force astronaut. He had every expectation of one day flying into space, doing his part in his country’s race to the stars. Meanwhile, he was doing one of the things he loved best: imparting hard-won flying knowledge to another pilot. He had led a good life, but Major Robert Lawrence had just a few minutes left to live.

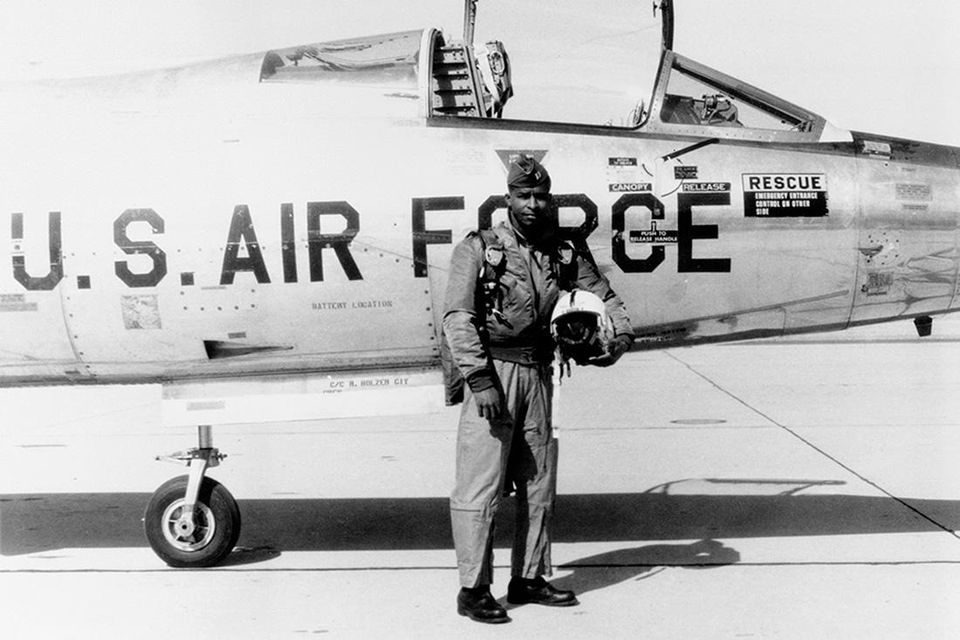

Major Robert H. Lawrence, Jr. in front of an F-104 Starfighter, 1967. (Photo courtesy U.S. Air Force)

Royer piloted the aircraft to 25,000 feet, and made the first of several planned approaches to the airstrip, coming in hard to simulate the speed of an aerospace vehicle like the X-15. On one of these approaches, something went wrong. It is not recorded if either of the two pilots realized that the aircraft was coming in too hard, or whether they had time to react. The official accident report states that the F-104 hit the runway 2,200 feet from the approach end. Royer and Lawrence likely felt the two main gears collapse under them as the plane landed left of the centerline of the runway. The canopy shattered, exposing the two men to the outside desert air. They may have smelled the smoke from the underside of the plane’s flaming fuselage. After skidding 214 feet the aircraft became airborne briefly and then crashed back onto the runway, skidding off the tarmac and into the dirt. As the plane began to break apart and roll over, both men ejected.

The ejection system launched Royer more or less vertically. He survived the crash, albeit with horrible injuries. Lawrence was not so lucky. When he departed the F-104 the plane had already rolled, so the ejection seat launched him horizontally, slamming him into the ground. His death was likely instantaneous. Thus died the first African-American astronaut before he had the chance to fly in space.

Lawrence was buried in his native Chicago with full military honors, with eight of his fellow military astronauts in attendance, as well as the Mayor Richard Daley. The flags on public buildings were lowered to half-staff in mourning. His funeral was a public event, as much as it was a chance for his family to say farewell.

In a strange way, Robert Lawrence’s entire life was preparation for something he never got to do: go into space.

“He was scholarly and serious,” said Lawrence’s father, the elder Robert Lawrence, in an interview with Ebony. “As a small boy the expression on his face reflected a kind of dedication. But I didn’t consider him a precocious child.”

Every year for Christmas, young Robert asked for a newer, more elaborate chemistry set. The future astronaut had a love of science that began in his early childhood and lasted his entire life, and he had the discipline to see his dreams through.

“This may sound unbelievable,” said Lawrence’s mother, Gwendolyn Duncan, “but I don’t know of any occasion when I had to discipline either of my children. They had a discipline that must have come from within.”

When he was a child, Duncan told Ebony, the family purchased a piano that came with eight discounted lessons. The instrument was a great expense for the family, and Duncan “emphasized to Bob the importance of his making all the lessons.” Crossing the street on his way to one of the lessons, Lawrence was hit by a truck. The driver leapt out and offered to take Lawrence to the hospital, but Lawrence refused. He had a piano lesson to get to.

Lawrence graduated at 16 from Englewood High School, located on the South Side of Chicago, in 1952 in the top ten percent of his class. He went on to graduate from Bradley University, located in Peoria, Illinois, at age 20 with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry. He was a member of the ROTC and was the corps commander of that organization at Bradley. Lawrence received his commission as lieutenant in the Air Force upon graduation.

After undergoing flight training at Malden Air Force Base in Missouri, Lawrence spent the next several years posted at Fürstenfeldbruck Air Force Base near Munich, teaching flying to West German pilots. While he was stationed there he married Barbara Cress, whom he’d met several years before. They had one son, Tracey Lawrence, and returned to the United States in 1961.

Lawrence was on course for a lifelong career as a flight instructor, but he wanted more. He enrolled at Ohio State University’s graduate program in physical chemistry. By the time he achieved his Ph.D. in 1965, he had accrued 2,500 hours of flight time — giving him the unique characteristics necessary to become an astronaut.

“He was probably the best graduate student I’ve ever advised,” said Dr. Richard Firestone, his graduate advisor, in an interview with Jet. “He [was] very intelligent, and he worked very hard. In fact, he worked as hard as a grad student should, which is unusual…. Also [he had] a lot of courage… not the kind of courage one needs to fly a jet air craft, but intellectual courage. He was quite a resourceful student, the kind who thinks for himself.”

According to several accounts of Lawrence’s life, he applied to NASA twice and was turned down both times. Although NASA refuses to confirm this, it wouldn’t be unusual. Many talented pilots failed to make the cut. But in 1967, NASA wasn’t the only game in town. Although it is little remembered today, the Air Force had a space program of its own: a vision of military space exploration far different from the peaceful ideal promoted by NASA.

The Air Force’s manned space program started with the Dyna Soar, a rocket plane meant to be boosted into Earth orbit atop a launch vehicle. The military envisioned the Dyna Soar as a platform for carrying out real-time reconnaissance, to inspect and interfere with enemy satellites. In case of emergency, it was designed to perform space rescues. The cost of the project soared, and that — along with lingering doubts about whether or not the Air Force should even have astronauts — caused the program to be cancelled in 1963. The military shifted its manned space efforts to something even more ambitious: the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program.

The MOL was to be a small space station in polar orbit, crewed by two Air Force astronauts whose missions would last about a month. The MOL would be equipped with a photographic system called Dorian, which had a higher resolution than cameras then available on unmanned satellites. The two astronauts would photograph targets on Earth as part of an ongoing reconnaissance program. Other duties for the MOL crew might include operating a radar system, testing electronic intelligence-gathering devices, assembling other orbital space stations, and inspecting enemy satellites. They would, in effect, be spies in outer space. Six months before he died, Lawrence was chosen to join their ranks.

When he was tapped for the project, the MOL was still just an idea, so Lawrence’s duties were strictly ground-based, such as traveling to visit contractors that were involved in the project. These trips were done under the radar, with officers like Lawrence wearing civilian clothing and even using assumed names. This arrangement proved to be a problem for Lawrence, as he had already achieved some measure of fame in the media as the “first black astronaut,” even though the program he was a part of was considered secret.

Lawrence was often accompanied on these trips by fellow MOL astronaut Donald Peterson, a white officer who hailed from Mississippi. At the time, young white men and young black men traveling together was rare. Often restaurants would not serve them, even though the practice had been made illegal under the Civil Rights Act that had been passed a few years before. Peterson, though born in the segregated south, was boundless in his admiration of Lawrence, referring to him as a “real super guy” decades after his death, according to NASA’s oral history. Many of Lawrence’s friends remember his good humor with fondness. Peterson went on to join NASA and fly on a space shuttle mission.

Major Lawrence was well aware of his status as a role model for African Americans and of the difficulties he and other black people faced in the turbulent 1960s, but he tried to avoid relating his career to the civil rights struggle. At a press conference with the other MOL astronauts, Lawrence was peppered with questions about his race. He avoided addressing such questions directly, declaring, according to Jet, that he was “a scientist, not a sociologist.” Self-effacing, he refused to compare his selection as an astronaut to the then pending nomination of Thurgood Marshall to be a justice of the Supreme Court. Having a black man chosen as an astronaut, he said, was “just another of the things we look forward to in the normal progression of civil rights in this country.”

If he had a cause, according to a profile published in Ebony shortly after his death, it was for more black youth to enter STEM fields. He believed that his success was due to the encouragement of his family, and his luck in attending a remarkable public high school that turned out an exceptional number of engineers, scientists, doctors and lawyers.

When Robert Lawrence walked out to the flight line at Edwards Air Force Base for the last time, he had a future that was boundless as the heavens.

A year after Lawrence’s death, President Nixon cancelled the MOL project, calling it too expensive, and no longer necessary thanks to advances in satellite technology and NASA’s plans for Skylab. If Lawrence had survived, he probably would have joined the other Air Force astronauts, and been transferred to NASA. He likely would have flown on the space shuttle, and become the first black man in space. It was not to be.

Mark R. Whittington is the author of a book about the intersection of space and politics entitled Why is it So Hard to Go Back to the Moon as well as numerous works of fiction, including, The Moon, Mars and Beyond, The Last Moonwalker and Other Stories, The Man from Mars: The Asteroid Mining Caper, and the Children of Apollo trilogy. He has written about space for the Wall Street Journal, Forbes, The Hill, the Washington Post, and USA Today among other publications.