Black History

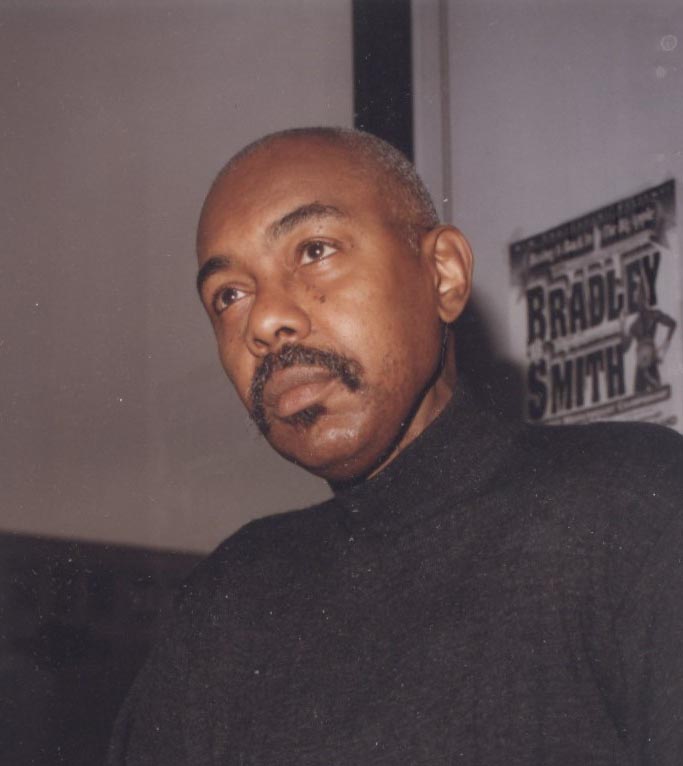

Eddie Ellis: Prison Reform Visionary

We interviewed the late Eddie Ellis at his 125th Street office in Harlem in 1997. At the time, Mr. Ellis was President of the Community Justice Center, Inc., an anti-crime research, education, and advocacy organization. Before he passed on July 24, 2014, he had founded and was president of the Brooklyn-based Center for NuLeadership on Urban Solutions and host and executive producer of the weekly radio program “On the Count” on WBAI.

Ellis had been a target of the FBI’s Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) for his Black Panther Party activities and had served 25 years in prisons throughout New York State.

While he was in prison, he earned a Master’s degree from New York Theological Seminary, a Bachelor’s from Marist College and a paralegal degree from Sullivan County Community College.

With other prisoners at Greenhaven, Ellis formed the Think Tank, an organization whose research showed that 75% of the prisoners in New York State come from just seven neighborhoods in New York City. It was this work that he and his fellow prisoners did that led us to this interview. It is the beginning of the 14,000-word interview to be posted at www.ourtimeathome.com.

David Greaves: I’ve heard you speak on WBAI, I heard you at Major Owen’s teach-in, and I said, “Yeah, this is the guy I want to speak to about this whole prison thing, and when you say, “this whole prison thing” you’re talking about a lot.

Eddie Ellis: That’s right.

DG: What is it that you see has to be changed in the prison and criminal justice systems?

EE: I think, first of all, prisons represent the failures of society, and the reason we have prisoners is because we have failures in society, given the nature of the society we live in. This capitalist, materialist, consumer-driven, society. Poor people have very limited ways, legitimate ways, of participating in the economy, except for public assistance. And almost inevitably, they find themselves, in some encounter with law enforcement. Usually over the acquisition of capital, trying to get money, they do whatever it is they need to do, and that almost automatically brings them into conflict with the law.

I belong to a group call the Community Justice Center. About 10 years ago, we did an analysis of the criminal justice system in New York State. What we found out was that over 75% of all the prisoners came from seven neighborhoods in New York City. The Black and Latino, the poorest neighborhoods. They have the worst schools, the worst housing, they have the largest percentage of families headed by a single head of household, the largest number of public housing, you just name it. They have the worst healthcare services, the highest rate of unemployment, highest rate of tuberculosis, highest rate of AIDS, highest rate of dropouts, highest rate of teen pregnancy – you name it. These communities are at the very bottom of the socio-economic ladder. Not surprisingly the overwhelming number of people who go to prison, come from these communities. So there must be some connection between living in one of these communities and going to prison.

DG: Sure.

- EE. The connection that we see, we call the prime generative factors. We say the social and economic conditions of a community pretty much determine whether or not a large percentage of people who live in that community, will or will not go to prison. And when you have communities that are so socially and economically devastated as these communities are, you will additionally have a disproportionate amount of people coming from those communities with problems with the law and wind up in prison. And the converse is true, where you have communities where the social and economic factors are standard or above standard and the standard of living is high, then you have very few incidents of people going to prison. So the key to prison seems to lie in the neighborhood. And the key to the neighborhoods seem to be the social and economic condition. So it seems to us that if all of that is true, and it certainly is true, then the criminal justice system should be a system that ultimately is aimed at or directed toward some way in which you address social and economic problems. And as you address those social and economic problems, you will find less and less people who you have a need to put in prison, which means you’d have less need for prisons. If I had my druthers, I’d close 98% of all prisons down. I’ve spent time in prison myself, 23 years in prison.

DG: Where were you?

EE: I was in every prison in New York. Every maximum security prison in New York. I was in Greenhaven, I was in Attica in 1971 when they had the insurrection, I was in Clinton, I was in Comstock, I was in Sing Sing, I was in Coxsackie, you name it, I was there. So I speak not just from an academic perspective, but from an experiential perspective. I’ve lived in prison, I’ve worked in prison, I studied in prison, I went to college in prison, I educated myself over the 23 years that I was in prison. I have 2 associate degrees, I have a Bachelor’s degree, and I have a master’s degree, while I was in prison. And I’m affiliated with a group of men who are also on that educational track.

We did a lot of things while we were in prison, one of which was this study.

At the time that we released the study, it wasn’t that well received. This was over 10 years ago. But over the last 10 years, it has gained more and more credence, more and more prominence, because it speaks to a really horrendous kind of condition. In ’92 we were fortunate enough to have the New York Times publish the findings of our study. They did an article on our organization on the front page and that kind of like catapulted us into the forefront of the criminal justice debate. The New York Times called us the “New Penologists.” There are about 25 of us in the organization, the Community Justice Center. And we’ve been trying, over the past 5 years to impact the criminal justice debate about prisons – who goes, why they go, the whole question of sentencing, the role of prisons. All of these things are very unclear. You talk to five different people about prisons, you’ll get five different answers, depending on who you talk to about what the fundamental role of a prison should be. Some people say that it should be for incapacitation, that there are certain people that are so violent, so antisocial that they have to be incapacitated, taken off the street and put in prison. Some people say that prisons function as a deterrent. that if you give a man or a woman a harsh enough sentence, if you put them away for a long enough time, that will “A” deter them from committing another crime, and “B” deter other people who see the kind of treatment that this person got, will deter them from committing another crime.

So you’ve got people who think the fundamental role of the prison is deterrent. You’ve got some people who believe the role of the prison should be punishment. It doesn’t have anything to do with deterrence, it doesn’t have to do with incapacitation, we just need to put people in prison and make them suffer. Because they made other people suffer. They robbed somebody, raped somebody, killed somebody, and they need to suffer for that. You’ve got other people who believe that prisons should be someplace people go for rehabilitation. You put a person in prison, they made a mistake, they committed a crime, that we can’t just give up on people, that the human potential is salvageable, and that prison is a place where some meaningful activity takes place, and where rehabilitation is the goal. There are some people who say prisons are all of the above.

So there is such a diversity of opinion about the role of prisons, that most people who are policy makers come down in one of the various areas. At different times throughout the past few decades, we’ve had people taking different positions. The people who are in power now, primarily conservative Republicans, feel the primary role of the prisons now should be for retribution and punishment, and that very little else should be going on in prison. And if prisons could be a place where people are severely punished, then whatever it was that they did, then they won’t do it again.

That presupposes a lot of factors that they don’t want to consider. The most obvious of which is that people who come from the neighborhoods we’re talking about, have very few options. And of the available options that they do have, almost inevitably they disdain those options. Because they’re not very attractive options. And particularly, we’re talking about young men, between the ages of thirteen and thirty who are the prime candidates to go into the prison system.

You know one of the things the right wing Republican people say is that the act of committing a crime is a personal decision that people make, and it’s a rational decision that people make. And I think on some level they’re probably right. It is a decision that people make. It’s a fairly rational decision that people make, but it’s a decision that is conditioned, that is constrained by a lack of viable options. If you’re a sixteen year old, seventeen year old kid, and you went to a high school or junior high school in which over 70% of the children in the school are reading and writing and doing mathematics below the grade level, and the teachers in that school really don’t give a damn one way or another about you, they don’t look like you, they don’t come from your neighborhood, they don’t have a stake in your education, and at the same time you’re the second or third child in the family, in which the father’s not present and the mother is struggling to make ends meet, and she very often is not at home, and you’re living in a substandard housing development, or in a tenement, and the options that are available to you are very limited. And one of the most attractive options that are available is going to be doing something outside the so-called legitimate areas. So a drug dealer comes along and says he’ll give you a hundred dollars a day to watch the package or to sell the package or do something with the package, what are you going to do, tell him no? As opposed to getting a job at McDonalds flipping hamburgers for $ 4.15 an hour?

DG: Listening to you, I’m thinking that it can be said that you have to pen up the sheep but cage the lions, and you have these young people who as you say are, to look at it the other way, these kids are proactive, who are aggressive, who have a need to achieve despite, and who select ways that are open to them, channel that rage, and I’m looking at you here, having circulated in prisons, what kind of people are in prisons. The impression given is that they are not like you. Are there more people like you in prisons?

EE: The best and the brightest and the smartest and the toughest of our young people are in prisons. The best. And I say that they’re the best because I think that they made some very serious decisions about their lives, about the way that they wanted to live their lives, and they have rejected I think the idea that they will allow the social and economic conditions to beat them down. So what they did is to defy the law, they became outlaws. I think in them you see a warrior spirit, a spirit of rebellion, a spirit of resistance, but it’s misguided spirit. A spirit that’s very destructive, an anti-social spirit and it’s the kind of energy, that instead of blossoming into something magnificent, has turned inward in a very pathological kind of way. And has been at the same time, self-destructive as well as destructive of the community around us.

A lot of that has to do with the influences that have shaped these kids. These kids are for the most part the creations of the media age, of a country that glorifies violence, the most violent country in the history of the planet earth, a country that teaches as a fundamental lesson of its history, that the way in which problems and conflicts are solved, are through means of violence and that might makes right. When there is a problem anywhere in the world, we send in the marines to kick they ass and straighten that business out. Granada, Iraq, Panama, Korea, Vietnam.

DG: You say the best and the brightest are in prisons, but a lot are not. I think of myself, I think of my wife, she is one of 16 children raised in Bedford Stuyvesant, I’ve been on welfare, food stamps, raised by a single parent, left back in elementary school, and yet both of us managed to stay out of the clutches of the police, and we’re not alone. We’ve been meeting many intelligent and motivated young people who have not gone the prison route. So I guess my question is, could some of the best and brightest have missed that net?

EE: Oh yeah, absolutely. When I said they were the best and the brightest I didn’t mean to be exclusive, to say that some of our best and brightest are not in the street. I believe that in the next 10 years, particularly going into the 21st century, the leadership of the Black community is going to come out of the universities and out of the prisons. So some of our best and brightest don’t get caught up in the trap. For whatever reasons. Part of the reasons are – we talked about our analysis of the Crime Generative Factors, and those Crime Generative Factors impact on people in different kinds of ways. And generally what happens is that there is some intervention in young peoples’ lives, some very positive intervention. Whether it’s from the family, whether it’s in the church, or the mosque, whether it’s in the school through athletic achievements or academic achievements, there is some positive achievement in most young peoples’ lives which set a course for which way they go. Those young people that don’t have that positive force, that positive intervention in their lives, or who ignore it, almost inevitably wind up in conflict with law enforcement.

DG: Because the human spirit will express itself in some way.

EE: there you go.

So you can get 100 kids born and raised in Harlem or Bedford-Stuyvesant and out of the 100 kids you can expect 60 of them are going to prison. The other 40 are not going to go. So you have to ask yourself, what happened with the other 40 that kept them from going. In many cases, just the grace of God. In addition to the grace of God, and this is based on research, there is some positive intervention. Some coach, some mother, some parent, some friend of the family, some pastor, who has taken a personal interest in this kid and who has helped motivate this kid in such a way that he or she has been able to navigate some of the pitfalls and not fall in that trap. But if you look at the statistics, the statistics say that right now, 1 out of 3 Black men in New York, between the ages of 20 and 29 are either in prison, on parole or on probation. That’s thirty-three percent, one-third. Now six years ago, in 1990, when they originally did the study, it was 1 out of 4. So it’s increased like 8% in 6 years. If it increases another 8% in the next 6 years, we/re talking about 41%, you know what I’m saying? We’re talking about 4 out of 10 after the turn of the century. These are young Black men. So the numbers seem to be getting larger and larger. And that figure is not just New York. That figure is constant for the entire country. So even though there are these positive interventions in most of these young people’s lives that have deterred them from having that encounter with law enforcement, the incidents are getting greater and greater.

DG: And this is happening as the children of the civil right era of consciousness are coming into their own. It seems that they are the ones falling down on the job. That is my generation from that civil rights era, and yet our children and grandchildren are the ones falling into this.

EE: the major problem is that, there’s a guy named Kunjufu, Jawanza Kunjufu, I don’t know if you’re familiar with him.

DG: Yes I am. He wrote “The Conspiracy to Destroy Black Boys.”

EE: He did a study not too long ago, and what he found out was that 25 years ago when we were coming up when we were young adults, the major influences in our lives were first family, then the church, then the school. Today the major influence in young people lives are peer pressure and television. The peer pressure and the television have replaced the family, church and school, as the dominant influence in these kid’s lives. So, you’ve got kids learning from kids, and all of them are learning from television and media. And what’s projected in that media is so pervasive, in terms of African peoples, the images we see on that media are distorted images. If your mind is young and you’re susceptible to those images, you internalize them. You begin to believe that in fact is you. And what happens, if you notice with these kids, is that they begin to emulate what they see on television and in the movies. They dress the part, they talk the language, they walk the walk, and the become what that image has laid out. And that’s been a major problem. I don’t know how we deal with that problem, other than to be able to impact the media in such a way that we begin to send some positive messages out, and we begin to use that media in other kinds of creative ways.

DG: In some areas, prison is almost seen as a Rite of Passage, as something you would do in a normal state of affairs.

EE: Absolutely our kids go to prisons the way white kids go to college. Looking forward to it. “Because after I come back doin’ my little three years, five years, whatever it is, that’s like the signal to the neighborhood that I’m a legitimate guy, I’m a tough guy, I’m a gangster, and all those other kinds of terms that go with it.

DG: They are now a player so to speak.

EE: Look, most of the heroes in American History have been men who resolve conflict by means of violence. Starting with George Washington, Davy Crockett, Daniel Boone, great American heroes all of them Andrew Jackson War of 1812, Billy the Kid, Jesse James, we glorify these guys, John Gotti, we make these guys into larger than life heroes and we present these guys as being what manhood is about. John Wayne standing tall in the saddle with a gun at his side straightening out all these other people who haven’t gotten the message yet. Ronald Reagan even, with that cowboy persona. This is what our kids get Our kids get this from the cradle to the grave. Then they have the availability of some of the most horrendous weapons of war. We’ve got these Glocks, the Mak 10’s, uzis, these guns don’t come from our community, but the kids have a way to get them. They’ve been infused with this sense of violence tied up with their manhood and a sense of conflict resolution based on might, the stronger you are the more right you are. Might makes right. It doesn’t make any difference if you are right or wrong, if you can enforce your will on someone else, you’re all right. So by the time this kid is twelve or thirteen years old, he’s in a mix where he’s constantly bombarded with consumerism. In order to be somebody you’ve got to have Air Jordans, Nike, and this and that, designer names and you don’t have any money.

DG: So the kid is the target of these multimillion dollar campaigns, and so is the parent.

EE: So is the parent.

DG: The advertising, the public relations, the media, the cigarette industry, the alcohol industry, all are trying to shape them, not in their best interest but in the best interest of the corporation. How is this resolved? What can come in there and break this cycle?

EE: Well that’s tough man, that’s really very, very tough. I think that most of the parents of these kids are themselves child parents. Women who had children at fifteen or sixteen. Now the kid is sixteen and she’s thirty-five or thirty-four, she grew up under very similar kind of circumstances, the father’s not present in the home, she has two or three other kids and she’s really struggling just to keep the household together and pay the rent and put the food on the table and do whatever little bit she can do. A tremendous amount of the young people who are in prison now, I don’t know what the numbers are, are from families on public assistance, over 70-80% are from public housing, or some kind of subsidized housing situation. So we’re talking about people who come from extreme poverty, not just poverty in the economic sense, but also poverty in the social, in the spiritual sense. And I think if we’re going to make any impact on these problems we have to deal with that aspect of the poverty of the spirit, and the poverty of the social problems.

DG: When you talk about spiritual poverty, that sounds like something the church should be involved in. What role do you see the church playing?

EE: I think that the churches and the mosques have not been as committed or involved as they could be. If you go to a lot of churches now, you won’t find many young people in the church. Particularly young males. Having said that, I think that more than anything else, the Black church has really stepped up. Certainly over the last ten years. We’ve seen a phenomenal stepping up of some of the Black churches taking up the slack. Because the governmental agencies, the fundamental institutions, are so racist and are so insensitive, and are so incompetent, that the churches had to step in there. So you see more and more churches involved in education, the have their own schools, more and more churches involved in day care, senior citizens. You see large developments in Brooklyn, the Bronx, Manhattan, Queens, the construction and rehab of abandoned properties, the church has ha to fill this void, because government has abdicated it’s responsibility and because the private sector is about making profit and capitalism.

DG: you make them sound like an important piece to the puzzle.

EE: If it wasn’t for the Black church, can you imagine where we would be right now. If you pulled the Black church money and the kinds of programs that they’re running…the Black church is the major operator of social programs in the Black community. A number of these churches have contracts with the government to provide services that the government doesn’t want to provide anymore. You talk about privatization, the privatization should come through the Black church.