Black History

Stolen Land, Stolen Labor: The Case for Reparations

The discussion of reparations comes at another turning point in American history. The Supreme Court has ruled that partisan gerrymandering is outside of court control. This means that the Republican Party, now controlled by white supremacists, will continue to cement their voting power by devising voting districts that favor their control and cram all others into fewer districts than they deserve. They will continue to dominate state legislatures, and from their safe seats, Republican politicians put job before country and vote their gerrymandered constituency, regardless of how the majority of people stand on an issue.

And more white supremacist fascist judges will be given lifetime appointments, putting both Black and Brown people, as well as non-rich white people, firmly under the control of overseers with their laws, regulations of income inequality and the economic whips of marketing and chains of debt.

It is in this environment that the topic of reparations is being put on the table. And if Trump wins this next election, then there will be no more of that reparation talk. Just try and hold on to what you have.

In a 1998 interview with historian John Henrik Clarke, he said, “…if Black people don’t unite and begin to support themselves, their communities and their families, they might as well begin to go out of business as a people. Nobody’s going to have any mercy. And nobody’s going to have any compunction about making slaves out of them.”

This next election will determine who we are as a nation and it is good to understand where we’ve been, and the level of amorality white supremacists are capable of. They can whitewash as much as they want. The reality is revealed in the kind of world they have created when they first had complete and total control.

The articles below, started with a 1997 trip to the Cadman Plaza Business Library in downtown Brooklyn. I was there looking for banks to approach for advertising and was struck by how many of them were formed during slavery times. I found myself following the money instead of doing my other work and this sidetrack led to a place where the oft-heard “slaves built this country” is shown to be true in dollars and cents and answers the questions, “Why reparations?” “For what?”

In “Stolen Land, Stolen Labor,” we can count the slave dollars flowing across the country, and in Frederick Douglass’ “What to the Slave is Your 4th of July?” we see the pain and suffering for which no compensation can be made, but which must be faced and acknowledged.

Special Report

Our Time Press, January 1998

By David Mark Greaves

More money was invested in slaves than all stock-in-trade, including bank stock, incorporated funds and more. This is indicative of the value placed on an unpaid labor pool and with good reason. The land was virgin territory, which is useless in a money-based value system. The land had to be worked and built upon. It was the slave workforce that released the value of the land and made it income-producing.

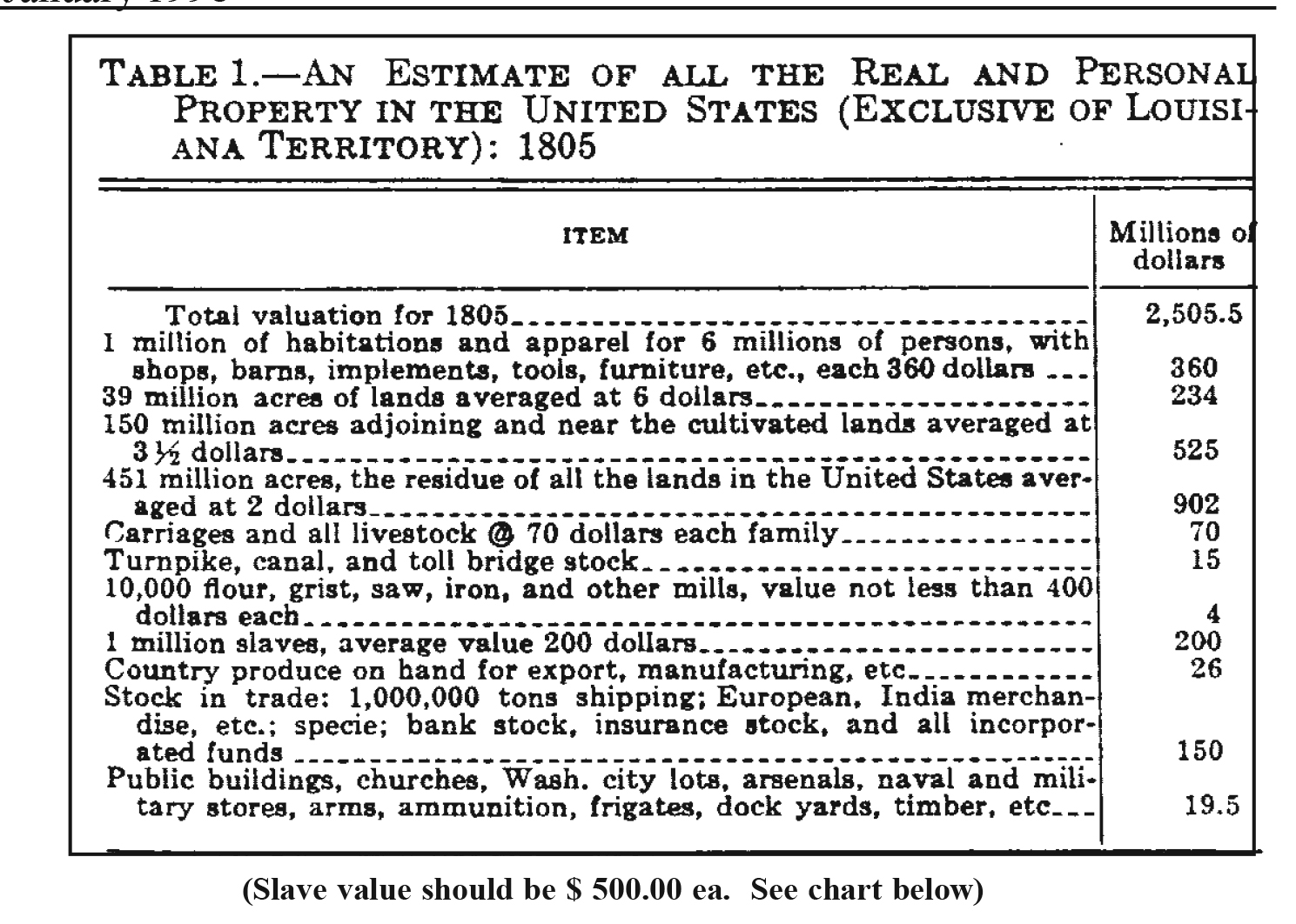

According to the U.S. Bureau of the Census, the first estimate of national wealth of the United States is found in Economica; A Statistical Manual for the United States of America, 1806 edition by Samuel Blodget, Jr.1 (See Table 1.) Of the $2,505 million dollars (2.5 billion) of national wealth, $1,661 million was in land stolen from the indigenous people, and $200 million was the value assigned to the slaves. Blodget writes, “Slaves are rated too high till they are better managed; everything else is below the mark.” The Historical Statistics of the United States 2 notes that, “No statement is made by Blodget as to the source material underlying” his tabulations.

And Mr. Blodget, by going out of his way to degrade the worth of the slaves, is telling us he may have something to hide, so we checked his figures. Taking the census of 1800 and averaging it with the 1810 census (not available to Mr. Blodget), we find him pretty accurate, and arrive at a slightly higher figure of 1,042,732 slaves. Mr. Blodget may himself have extrapolated from the 1800 census. In any event, knowing how much difficulty the Census Bureau had counting the descendants of the slave population in 1990, we can guess that these census figures are “below the mark.”

Secondly, we turn to American Negro Slavery: A Survey of the Supply, Employment and Control of Negro Labor As Determined by the Plantation Regime by Ulrich Bonnell Phillips (1966 p. 370), and find this: “The accompanying chart (see below) will show the fluctuations of the average prices of prime field hands (unskilled young men) in Virginia, at Charleston, in middle Georgia, and at New Orleans, as well as the contemporary range of average prices for cotton of middling grade in the chief American market, that of New York. The range for prime slaves, it will be seen, rose from about $300 and $400 a head in the upper and lower South respectively in 1795 to a range of from $400 to $600 in 1803…” By using these figures, we find that the minimum amount of money invested in slaves was $521,366,000 in 1805. Therefore, the total national wealth could be more accurately calculated as 2.8 billion dollars ($ 2,826,366,000) adding an additional 300 million to Blodget’s figure. This means that 77% of the total national wealth of the United States of 1805, ($2,182,366,000), was based on holding African Americans as property to work the stolen land.

In a civilized society, dollar value is not placed on human beings. Not so in early America. Here, the value of enslaved Africans is $200 ea. At a time when the market value was $500 “a head.” (See chart below showing how the price of “prime field hands” moved in relation to the price of cotton on the trading floors of the New York Stock Exchange, itself founded in 1792.

By 1856 there were 3,580,023 slaves, according to an average of the 1850 and 1860 census counts. Bear in mind here that in 1813 Congress laid a direct tax on property, including “houses, lands and slaves.” This meant that there was now an economic motivation to undercount this part of the owner’s property – the fewer slaves reported, the less taxes paid. Slaves were easier to hide than houses or land. This is coupled with the natural inclination of the Census to under-count the Black population. The evidence is clear in the General Population Statistics, 1790-1990. By 1860, the “Percentage increase in Black population over preceding census” averaged 28.8% since 1790. In the 1870 census, the percentage growth was only 9.9 %. So, what happened to the other 18.9% of the expected population? They disappeared in 1865 with the Emancipation Proclamation. No longer having a value attached to them, these 859,000 African Americans were lost. It’s been 120 years and, judging from the low-count controversy of the 1990 census, the Bureau hasn’t found them yet. We can safely regard these census counts as the way-down-low end of an actual population estimate.

Before a final figure can be determined of the debt due on this slavery phase of the African Holocaust, some account should be taken of the working conditions. You can get an impression by looking no further than the evidence found in the African Burial Ground in Manhattan, New York. Here, recent analysis of the remains held at Howard University show that children as young as seven were worked so hard that their bodies were misshapened and their spines driven into the brain, from carrying heavy loads. Ulrich Phillips, in American Negro Slavery says of J.B Say, an economist working around the turn of the 18th century, “Common sense must tell us, said he, that a slave’s maintenance must be less that of a free workman, since the master will impose a more drastic frugality than a freeman will adopt unless a dearth of earnings requires it. The slave’s work, furthermore, is more constant, for the master will not permit so much leisure and relaxation as a freeman customarily enjoys.” This is why we include the entire slave population as laborers, and we leave it to others to dare argue why we should not.

By 1856 the advertised prices for European-owned African-Americans on one document of that time ranged from a high of $2,700 for Anderson, a “No.1 bricklayer and mason,” and $1,900 for George, a “No. 1 Blacksmith,” to $750 for Reuben, even though he was labeled “unsound.” (See document on Page 7 .) “Credit sale of a choice gang of 41 slaves.” The average cost for this lot of people was $1,488. As a second reference for this number, we can look at the chart for the cost of Prime Field Hands, and find that it is pretty accurate.

By 1856 the advertised prices for European-owned African-Americans on one document of that time ranged from a high of $2,700 for Anderson, a “No.1 bricklayer and mason,” and $1,900 for George, a “No. 1 Blacksmith,” to $750 for Reuben, even though he was labeled “unsound.” (See document on Page 7 .) “Credit sale of a choice gang of 41 slaves.” The average cost for this lot of people was $1,488. As a second reference for this number, we can look at the chart for the cost of Prime Field Hands, and find that it is pretty accurate.

By multiplying the census count of slaves by the average advertised price, we arrive at a value of $5.3 billion ($5,327,079,968). This may not look like a lot of money now but compare it to other figures of the day. The National Wealth Estimate for the entire nation in 1856 was $12.3 billion ($12,396,000,000). [Note: All figures, come from Tables in the cited U.S. Bureau of the Census publication] Total Bank Savings Deposits in 1856 was $95.6 million. Manhattan Island, Land and Buildings was worth only $900 million dollars, less than one-fifth of the value invested in African Americans. The 1855 total capital and property investment in railroads was only $763.6 million dollars. Why the $5 billion investment in slaves? In 1859, the total private production income was $4,098,000,000 ($4 billion). Of this total, labor-intensive industries like “agriculture” and “transportation and communication,” accounted for $1,958 million (1.9 billion), almost one-half the total private income. This explains why “a good field hand and laborer” would run you $1,550 for Big Fred aged 24 and $ 1,900 for George, a “No. 1 blacksmith.” Men like these gave such a good return on the dollar that their owners would, and did, kill freely to keep the system in place.

The money earned from this investment found its way into a variety of banking institutions, which increased from 506 in 1834 to 1,643 in 1865. Many of the names remain familiar to this day: The Bank of New York Company, Inc. – founded 1784,3 Fleet National Bank – 1791, Chase Manhattan Corporation – 1799, Citicorp/Citibank N.A. -1812, The Dime Savings Bank – 1859. As banks in King Cottons’ “chief American market, that of New York,” it is inconceivable that these institutions, and through them the nation, did not benefit from the profits made on a slave’s wages. Their business then, as it is now, was to be a source of funds to build empires in a variety of industries, across the continent, to make land purchases, upgrade equipment, save to send children to college, etc. Railroads could be built using a combination of slave labor and loans taken at banks that held money on deposit from the cotton/slave industry. Money was also paid to a variety of people who, while not slave-owners themselves, were “in the loop” of payments for goods and services. Thus, were assets being used to develop the country, for the benefit of Europeans and their heirs. The nation as a whole benefitted, and that’s why the nation as a whole should pay—with the exception of the descendants of enslaved Africans.

When we take that figure of $5,327,079,968 and compound it annually at 5% interest for 142 (1856-1998) years, we arrive at $ 5,437,129,590,059 or 5.4 trillion dollars. The 5% interest rate is actually a modest one. We would much rather have employed the interest paid on Railroad Bonds in 1857, with yields of 6.577 (low) to 8.23 (high), but the computer calculator ran out of room and the lower rate had to be used.

Recently, the Jewish community has begun demanding that Swiss banks which received deposits of money and valuables confiscated from Jews by the Germans, repay the principal of those deposits with interest. They have received Congressional support, had a respectful hearing, and are seeing the Swiss banks begin to comply and total accounts. The Jewish Holocaust ended in 1945 with the surrender of Germany. The slavery period of the African Holocaust ended only 80 years earlier in 1865 with the surrender of the southern states. It was at that time that the right to own African Americans outright, was given up throughout the United States.

In recognition of the wrong done, Congressman John Conyers has sponsored a reparations bill, H.R.40: “A bill to acknowledge the fundamental injustice, cruelty, brutality, and inhumanity of slavery in the United States and the 13 American colonies between 1619 and 1865 and to establish a commission to examine the institution of slavery, subsequent de jure and de facto racial and economic discrimination against African Americans, and the impact of these forces on living African Americans, to make recommendations to the Congress on appropriate remedies, and for other purposes.”

Twenty-five years ago, Queen Mother Moore was at the First Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana. There she stood in a hotel lobby wearing African clothes, handing out literature and accepting hugs, while shouting, “Reparations! Reparations, Honey! Come get your reparations – They got to pay you!” The Queen Mother was right. It is in the context of reparations that the nation should be discussing affirmative action – as part of the mix of options a moral nation would consider in paying a long-due debt. Thirty percent of the nation’s airwaves could be an option. Funding of African American banks could be another. Government contracts should be the easiest, with a mandated percentage for each line-item going to African American businesses on a sliding scale well into the next century.

Five trillion dollars may seem like a lot of money, but if Congress can seriously consider a trillion-dollar weapons system now working its way through the appropriations pipeline, then a 5.4 trillion-dollar reparations bill is doable over time. This number is only for the slavery phase of the African Holocaust. It does not include the theft of property rights, inventions and patents. It does not include damages for pain and suffering. It does not return lost lives. It is an attempt to be another voice in the reparations process.

Until this debt is acknowledged and paid, America will forever be paying in blood, tears, and the devil’s wages.

1[Historical Statistics of the United States 1789-1945, a Supplement to the Statistical Abstract of the United States, U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, published in 1949 by the United States Bureau of the Census. Chapter A. page 1.]

2Ibid.

3 All founding dates are from the Standard Directory of Advertisers. Published by the National Register.

More on the Economic Impact of Slavery

Our Time Press February, 1998

Slavery is often looked at as a blot upon humanity rather than the business decision it is. Africans have been presented as lazy, shiftless, good for nothing, when the exact opposite was true. We were a vital necessity to this nation. Africans were the most valuable resource, our value on the open market dwarfed all other industries and values except for the land itself.

Slave-holding families “On the average of 5.7 to a family there are about 2,000,000 persons in the relation of slave-owners or about one- third of the whole white population of the slave States; in South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, excluding the largest cities, one half of the whole population.” DeBow

Historians talk about the Industrial Revolution starting in 18th century England, and the computer/information Age of today. Left out is the Slave Age, that period of the dark days of the golden age of white affirmative action. This was the time when the United States, an emerging nation at the time, dealt most efficiently with a formidable problem: the supply and cost of manual labor.

A headline in the New York Times dated Tuesday, January 13, 1998, reads, “Software Jobs Go Begging, Threatening Technology Boom.” The Times points out “As America relies more heavily on computer software than ever before, the demand for people who can develop and use the tools of the modern age has vastly outstripped the existing supply.” “If the talent drought continues, the entire national economy may feel the effect of lost wages and slowed innovation… ‘This is like running out of iron ore in the middle of the Industrial Revolution,’ said Harris N. Miller, president of the Information Technology Association of America.” Mr. Miller is in error with his analogy. Running out of silicone in the Technology Boom, would be like running out of iron ore in the Industrial Revolution. But running out of computer programmers (the workers) in the technology industry, is like running out of slaves during the Industrial Revolution.

In 1850 The New York Times headline would have read, “Manual Labor Jobs Go Begging, Threatening Industrial Boom.” African American slaves were the critical workers of the Industrial Age in the United States. In the same way that programmers transform computer code into products, so the labor of slaves transformed raw materials and land into products that would allow the Industrial Age to flourish in this hemisphere.

Information technology has grown into the largest industry over the last thirty years. Slavery was the largest industry from the time such things were first measured in 1805, until African Americans were freed to be paid labor in 1865.

At $865 billion a year, information technology represents about 12% of the 1997 Gross Domestic Product of $7,214 billion. In 1805 slave labor represented as much as 20% of the national wealth. By the 1850’s through ‘60’s that figure rose to as high as 40%. If a 12% industry like information technology can affect the entire nation, how much impact does a 20-40% industry have? Let’s take a look at the 1850’s and the effect of slave labor on the economy.

According to J.D.B. DeBow, writing in the Seventh Census 1850 Statistical View, Compendium published in 1856, “The total number of families holding slaves by the census of 1850, was 347,525. (See U.S. Census Table XC below). On the average of 5.7 to a family there are about 2,000,000 persons in the relation of slave-owners or about one-third of the whole  white population of the slave States; in South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, excluding the largest cities, one half of the whole population.”

white population of the slave States; in South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, excluding the largest cities, one half of the whole population.”

In his work, History of American Business & Industry, Alex Groner observes, “In the sense that they were large and complex producing units, the big plantations were the South’s factories. The hundreds of slaves included large numbers of production workers – the field hands– as well as such specialists and skilled artisans as carpenters, drovers, watchmen, coopers, tailors, millers, butchers, shipwrights, engineers, dentists, and nurses…Because virtually entire families could be put to work in the fields for most of the year, the slave economy proved ideal for cotton culture. The price of a good field hand, about $300 before Whitney’s invention, doubled in twenty years. Poor whites, who could afford neither slaves nor land at the higher prices, moved west in mounting numbers and soon dominated the Southwest……It was not only the plantations of the South but also the factories, shipping merchants, and banks of the North whose economies became tied more and more closely to cotton. What north and south had in common was the prosperity resulting from the growth of cotton production. The size of the crop climbed steadily, from 80 million pounds in 1815 to 460 million, or more than half the world’s output by 1834, and to more than a billion pounds by 1850…..From 1830 until the Civil War, cotton provided approximately half of the nation’s total exports.”1 At an average of 400 man hours per 400 pound ginned bale of cotton, (based on census averages), these billion pounds required a billion hours of unpaid man-hours. These were supplied by African American men, women and children, working as slave labor, under threat of torture and death.

Thus produced, the cotton crop traded hands on exchanges like the largest one in New York. Longevity counts in business, and many banking institutions trace their founding origins back to that time including, Bank of Boston -1784, Brown Brothers Harriman 1818, Chase – 1799, First Maryland Bancorp – 1808, Fleet Financial Group, Inc. 1791, J.P. Morgan, Co. Inc. 1838, to name a few. U.S. Trust of New York, 1853 was only a gleam in some banker’s eye at the time, and Price Waterhouse, the famous accounting firm had just gotten its start in 1849. These banks and other businesses participated in cotton transactions that were all handled as they usually are, for a fee. And so, the brokers, traders, lenders, etc. all profited first. Then came the employees of the firms, the landlords, the washerwomen, the street vendors, messengers, haberdashers, milliners, and all their families and mortgage-holders and service-providers, in an ever-widening circle.

SLAVE CROPS TOTAL MORE THAN 60% OF NATION’S EXPORTS

Now traded, the cotton found its way to 25 of the 35 states and territories for manufacturing. We don’t have to assume how the product was distributed; we can look at the 1850 list of cotton manufacturers. (See U.S. Census Table CXCVL) Here we see there were 1,064 businesses directly employing over 92,000 people across the country.

Leading the way is Massachusetts, using 223,607 bales of cotton while employing over 29,000 people. It is also interesting to note that the export of slave-crops of cotton, tobacco, and rice, totaled over 60% of all the nation’s exports. This meant that the shipping industry, the dock workers, and the factories on both sides of the Atlantic, all made a living from the peculiar institution of African Americans working as slaves.

It was possible for people throughout Europe to work in cotton factories or peripheral industries in their home countries, save their money, and book passage to America. Here, the newly arrived immigrant could get off the boa, and work selling apples on Wall Street to the employees of the Cotton Exchange. A seamstress from English mills could come and find work making dresses for the wives and mending the coats, of the men who worked in the financial district. Maybe you’ve heard stories like these before.

When an industry produces over 60% of the national exports, it reaches farther than can be seen from the docks or from the fields. And there were other crops as well. There were 2,681 sugar plantations, and 8,327 hemp planters. In 1850 there were over 20 million bushels of sweet potatoes, 3 million bushels of Irish potatoes, 7 million bushels of peas and beans, and 8 million pounds of wool, all produced in slave-holding states. The African Americans that Europeans called ne’er-do-well, helped clothe and feed this nation when the Europeans couldn’t.

GOVERNMENT PROFITS MOST

The government profited most of all. The export of slave-produced crops allowed this emerging nation to import from the more industrialized countries (with tariffs applied), without incurring a trade deficit. Also, slave-intensive industries such as agriculture, manufacturing and transportation comprised over 60% of the total private production income at the time. In one way or another, this money was taxed. The slaves themselves were taxable as property beginning in 1815.

The Federal Government profited by first placing a tax on the slave as a unit of property, and again when taxes were paid on the land the slaves improved. Taxing authorities, whether federal or local, made their money at some point in the trading of cotton and again when salaries found their way into taxable areas. The government uses a myriad of ways to raise the money it needs to do what it has to do – to build the infrastructure of the nation. To build the roads, forts and pay the federal marshals. This was done, in a large part, with slave dollars flowing like an irrigating stream, watering national, state and local governments at various stops along the way.

And now today, the United States stands as a money pump with $7 trillion worth of pressure, creating jobs for Joe Blow in Idaho, and millionaires and billionaires with fortunes that span the globe. But it is a pump that was primed with the blood of African and Indigenous people. This is a fact that must be recognized, and African Americans must recognize it first of all.

2019 Postscript: Big numbers calculator app and total Reparations due.

Using the amount invested in enslaved Africans as the principal: $5, 327,080,110.

At 6.77% interest compounded annually for 142 years with an inflation rate of 3% per year, the total comes to $58,382,365,074,358.98 or $58.3 trillion. Nobody expects an immediate check and we extended the courtesy of not running it to the current year.

However, if even that amount due is paid through the myriad means of government, using sort of an updated WPA that includes business-building and education components, at a rate of a trillion dollars a year for 58 years, we would see such a growth and a renaissance of national brilliance being unleashed, that it would power unimagined economic and artistic expansion.

It would open doors in science, we didn’t even know were there. Do that, and in 2100, all will fall back in wonder and thankfulness at what we have done.