Black History

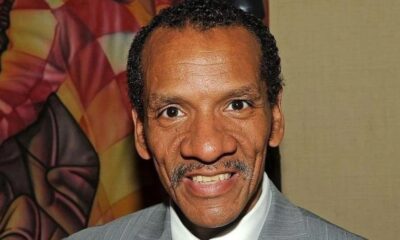

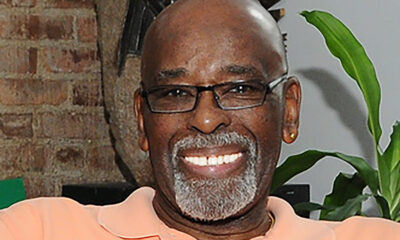

Ralph Carter on Dr. Albert Vann,

“A Major Force… and a Beacon for Young Men”

In the 1970s, fresh off a Broadway Tony Award nomination for the musical “Raisin,” Ralph Carter, a Black teen from Brooklyn became a television star on the landmark comedy series “Good Times.” His character Michael Evans was a teen community activist. Growing up in Brownsville and Bed-Stuy, Carter was mentored by New York’s famed frontline community activists Rev. Herbert Daughtry and Al Vann. In this Q&A, Carter talks about the impact of Al Vann.

OTP: You are a lifelong Brooklynite. Do you remember how you first knew about Al Vann?

RALPH CARTER: When I was a little boy in 1968, Pitkin Avenue used to be the epicenter for shopping for African people and all people of African ancestry who lived in Brownsville Brooklyn, where I’m originally from. I remember my mother took me to John’s Bargain Store on Pitkin Avenue and bought me all my school supplies and new clothes. I was shiny as anything that day. However, everything came to a halt when the school system went on strike. I remember distinctly that I wasn’t going to go to school that day. When I grew up. I found out that brother Al Vann, along with Sonny Carson, Rev. Herbert Daughtry, Jitu Weusi, and other men in the vanguard of that time, were at the forefront of literally fighting for the minds of African children and who would teach our children and who would be in control of the educational system. Later, I was introduced to Al Vann by Rev. Herbert Daughtry, who was my first mentor after my father. Rev Daughtry set an example to me of how you can get a total contingent of Black men to work together for a common cause. At the center of that, of course, was Al Vann.

OTP: What did you personally admire about Al Vann?

RC: I found that Al Vann’s humility was unimpeachable. I think he was consistently one of the most gentle spirits that I personally met walking this planet. What I also admired about him, and I still do, is that he was recently helping us build this wonderful museum in Restoration Plaza. Brother Al Vann had an integral role in having the cultural Museum of African Art in Brooklyn, which is spearheaded by artist Eric Edwards. He has one of the greatest archives of African artwork. Al Vann was a major force and made things happen for us at Restoration. Also, I am eternally grateful to him because of his connection with the Billie Holiday Theater and through the grace of people like former director Marjorie Moon and Woodie King, who have great artists perform at that wonderful theater. Al Vann was able to reach so many people–like helping out with Boys and Girls High and the work that he was doing at Medgar Evers College. One of the last brilliant meetings that I had with Al Vann, along with Rev. Daughtry, was to receive a gracious grant of $1 million with artist Eric Edwards to build the Museum of African Art at Restoration Plaza. This was done, through the gracious assembly member Stefani Zimmerman. Al Vann and I sat together during the whole meeting process. He was integral to the process of receiving the grant. He was in the trenches with us. That was part of his character makeup.

OTP: What did you personally learn from watching Al Vann’s expertise as a community organizer?

RC: I watched how he used his skills to get things organized. I observed his skills to bring people together. I was a young guy when I met Al Vann. It was through Al Vann, Rev. Daughtry, the great brother Jitu Weusi and Minister Clemson Brown. It was predominantly these fundamental men that I witnessed doing things that helped shape the borough of Brooklyn. I’m talking about changing the names of streets like Harriet Tubman, because children should know about her. People like Al Vann are very rare. They follow through on what they say they are going to do. But, also to have the humility to join ranks with other people in a collective process to achieve the same goal. That’s what the impact of Al Vann has been in my life. That’s something that I can keep for the rest of my life.

OTP: How Al Vann personally inspire you?

RC: I am very grateful to be the recipient of great Black men in my life. I have been influenced by a lot of brothers, who not only showed me how to study history, but also to implement it. I met Dr. John Henrik Clarke when I was 13 years old. This also has to do with Al Vann because he was an intricate part of the work Rev. Daughtry was doing in his church. When they assassinated important Black people in our communities like Randolph Evans (a 15-year old that was shot by NYPD in 1976 in Brooklyn). Also Arthur Miller (a Brooklyn business-owner who was strangled in a struggle by the NYPD in 1978). Those were horrible, tragic events that happened in our community. You don’t forget people like that. Al Vann was a force in making sure our voices were heard and those particular murders did not go unchallenged. These are the things that as a young man I observed in my community. Paul Robeson once said that the role of the artist is also to change the way society thinks. I think that whether he was an artist or not Al Vann was able to change the ways society thinks. He was able to be a beacon for other young men, not just myself. I’m sure many in my age group were also impacted by his leadership in general but also by his humility. That’s what I really liked about him.

This is part one of a two-part Our Time Press series with Ralph Carter. In an upccoming issue, Carter explores his fascinating life in Hollywood and New York theater.

This interview was conducted by Fern Gillespie, the senior editor at Our Time Press and an award-winning entertainment journalist. She is a former board member of the NAACP’s Crisis Magazine and wrote for the NAACP Image Awards Journal on Black cultural issues.