Health & Wellness

Uterine Cancer at Crisis State for Black Women

By Fern E. Gillespie

When the New York Times released a story last week about the rising prevalence of uterine cancer among Black women, I was not surprised. Over the last 20 years, I’ve had several relatives diagnosed with uterine cancer including my mother and her sister. Both my mother and my aunt were diagnosed in their 70s and survived the disease. However, my mother had critical life-changing complications. Her abdomen was infected with necrotizing fasciitis (the flesh-eating bacteria), which landed her in ICU for six weeks and the remainder of her life in a nursing home.

According to the New York Times, cancer of the uterus, also called endometrial cancer, is increasing so rapidly that it is expected to displace colorectal cancer by 2040 as the third most common cancer among women, and the fourth-leading cause of women’s cancer deaths. Uterine cancer was long believed to be less common among Black women. But newer studies have confirmed that it is not only more likely to strike Black women, but also more likely to be deadly.

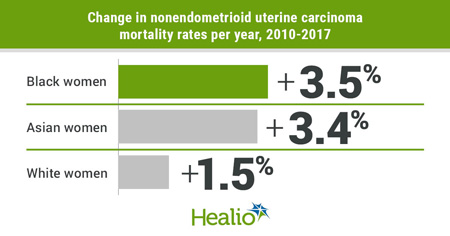

A March report from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists stated that Black women die of uterine cancer at twice the rate of white women. The gap is one of the largest racial disparities observed for any cancer. Black women are also more likely to develop a form called non-endometrioid uterine cancer, which is more aggressive. In addition, Black women were less likely than white women to undergo hysterectomy, less likely to have their lymph nodes properly biopsied to see if cancer had spread, and less likely to receive chemotherapy, even for a more threatening cancer.

Several notable Black women physicians, who specialize in gynecologic oncology, have been working with Black patients to study methodology and treatments to combat this uterine cancer crisis. At New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Dr. Carol Brown, a gynecologic oncology surgeon and MSK’s Chief Health Equity Officer, launched the Endometrial Cancer Equity Program (ECEP). Endometrial cancer develops in the lining of the uterus (womb) and is also sometimes referred to as uterine cancer. The program’s goals are to educate Black women about endometrial cancer, help those diagnosed find appropriate care, and ultimately find treatments to improve outcomes for all women facing the disease.

“Traditionally, providers have focused on symptoms that include bleeding in post-menopausal women, who often have other symptoms such as obesity and diabetes,” said Dr. Brown. “But this cancer can present as just a heavier-than-usual period bleeding in your 40s. That’s true of all women and particularly Black women.”

The ultimate goal of research at MSK’s Endometrial Cancer Equity Program is to better understand these biological differences in endometrial tumors, down to the molecular level, and then use this knowledge to identify weaknesses in the tumors that are more common in Black women. Then, it’s about finding therapies to treat them.

A study from the National Cancer Institute has shown that Black women with endometrial uterine cancer have a 90% higher 5-year mortality risk compared with white women. There’s a 5-year mortality rate of 39% among black women compared with 20% among white women. Only 53% of black women receive an early diagnosis.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) screening missed over four times more cases of endometrial uterine cancer among Black women than white women, pointed out Dr. Kemi Doll, the lead researcher, and a gynecologic oncologist with the University of Washington School of Medicine. She is a founder of ECANA: Endometrial Cancer Action Network for African-Americans.

“Black women have an over 90% higher mortality rate after diagnosis of endometrial cancer when compared with white women in the U.S.,” she wrote in her 2021 study published by JAMA Oncology. In this study using a simulated cohort, TVUS endometrial thickness screening missed over four times more cases of endometrial cancer among Black women versus white women owing to the greater prevalence of fibroids and non-endometrioid histology type that occurs among Black women.

Premenopausal women who have erratic menstrual cycles may not recognize that they need to check for uterine cancer because they think of the irregularities as normal, said Dr. Doll. And women in perimenopause who expect abnormal bleeding may also not recognize when something is wrong.

This disparity has been witnessed firsthand by Dr. Ebony R. Hoskins, a gynecologic oncologist at MedStar Washington Hospital Center and assistant professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology at Georgetown University Medical Center. “I’ve seen women who have the symptom of heavy bleeding or irregular bleeding, and the workup hasn’t been thorough like it should have been,” she told Health.com. Dr. Hoskins explains that a routine workup when any woman of any age presents with endometrial cancer symptoms—pelvic pain, heavy vaginal bleeding, weight loss—should include an ultrasound. Sometimes, it necessitates a hysteroscopy, a diagnostic procedure that allows a doctor to inspect a woman’s uterine cavity.

Black women undergoing treatment for gynecologic cancer reported significantly higher levels of race-associated stress compared with white women, according to a March 2022 study by Dr. Hoskins. Presented during Society of Gynecologic Oncology 2022 Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer, the study also showed that the racism Black women experienced resulted in increased treatment interruptions, longer time to treatment initiation, and longer treatment interruptions.

“Our study demonstrates the toll of racism experienced by Black women with gynecologic cancer affects their standard cancer care,” Dr. Hoskins stated in the press release. “Expanded studies are needed to examine race-related stress and its possible contribution to worse clinical outcomes in these Black patients. With further understanding, we can work toward solutions for more equitable cancer care.”