American History

Thoughts and Memories on Memorial Day

The true story about Memorial Day, and my memories of honoring a century of tradition.

Suzanne Spellen

outh Carolina was the first Southern state to secede from the Union in 1860. Charleston became one of the Confederacy’s most important port cities. Nearby Fort Sumpter, a Federal stronghold, saw the first active shots against the Union, which soon erupted into a long and extremely bitter and deadly war.

During the war Charleston was a vital blockaded port city, still receiving contraband goods from allies and shipping out cotton, all necessary for the South’s survival. Union forces fought to control Charleston for over four years, during which time much of the city was destroyed. It wasn’t until February of 1865, a month and a half before the end of the war, that the Union was able to capture the city.

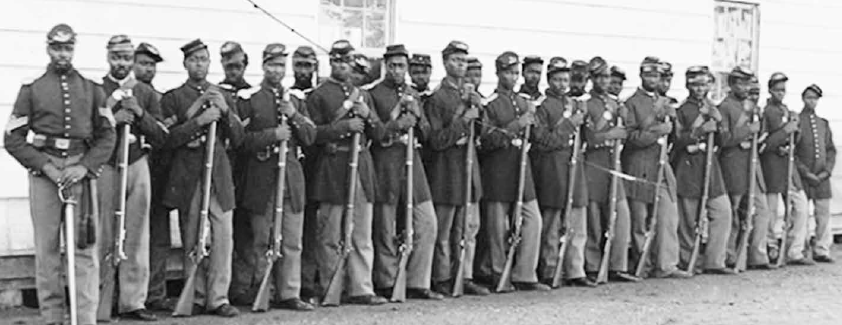

More than half the population of Charleston was enslaved. When the mayor of Charleston officially surrendered the city, it wasn’t by accident that the first Union troops to enter the city were the 21st Infantry Regiment and the 55th Massachusetts Infantry, both black regiments. According to historic records, they were met by thousands of black citizens of the city who cheered them as they rode by. Most of the crowd were still tasting their first months of freedom.

The African American regiments led the rest of the Union Army through the city, singing “John Brown’s Body,” a popular camp song that would not only the glorify the hanging death of Abolitionist John Brown, but the righteousness of the Union cause. “John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave. His soul is marching on. He’s gone to be a soldier in the army of the Lord, his soul is marching on. Glory, glory, hallelujah.”

One “official” version of the song has a verse that reads, “John Brown’s body lies a moldering in the grave, While weep the sons of bondage whom he ventured all to save; But though he sleeps his life was lost while struggling for the slave, His soul is marching on. Glory, glory Hallelujah!”

A great many people during this time claimed that they originated the song, which first appeared in print in 1861. Some versions were more reverential than others. The enduring rendition of the tune itself, with words by poet Julia Ward Howe, is the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” a song whose melody and words still have power to this day.

During the last year of the war, a planter’s racetrack on the outskirts of Charleston had been turned into a Confederate prison camp. The conditions there were horrific and at least 267 Union prisoners died, mostly of various diseases, and were buried in unmarked graves. Newly liberated black residents in Charleston wanted to honor their sacrifice, and two dozen men reorganized the graves into rows and put a large fence around them. A sign was placed on an archway over this burial ground which read, “Martyrs of the Race Course.”

Ten days later, on May 1, 1865, at least 10,000 people, mostly African American, marched solemnly to the track. They were led by 3,000 children who paraded around the track holding roses and singing “John Brown’s Body.” They were followed by those representing the new aid organizations for freed people, and the people themselves. Black pastors preached sermons and led people in prayer and in song. The hopes and aspirations of a people who had been enslaved their entire lives were made manifest in the singing of spirituals that spoke of faith and freedom.

Those who participated also sang patriotic songs, such as the “Star Spangled Banner” and “America,” and the celebration and memorial ended with three Union regiments, both black and white, marching around the gravesite and staging drills.

There are many other places and dates for the first “Decoration Day,” but this event, written about as it happened by several newspapers, both local and national, was one of, if not the first commemoration. It is only recently in 1996, when the events of that day were uncovered that this story regained its place in our history, correctly giving credit to African Americans for their contributions to this holiday.

But, twenty some years after the event, the erasure of this history was almost complete. In 1889, the bodies were moved to Beaufort National Cemetery and the land was turned into Hampton Park, named after slaveholder Wade Hampton III, a Confederate general, Charleston native and governor of South Caroline in 1876. No one mentioned the Martyrs of the Race Course in white Charleston again.

On May 30, 1868, General John A. Logan instituted a ceremony at Arlington Cemetery. He called for the laying of flowers on the gravestones and a ceremony to honor the dead. His call is given the credit as the first Decoration Day. May 30th became a national holiday in 1889, and now called “Memorial Day” was officially changed to the last Monday in May 1968. We’ve celebrated it with parades, flags and large retail sales events ever since.

But the theme of flowers runs throughout every commemoration of Memorial Day from the very beginning. Newspaper accounts and stories passed down through generations of black Charlestonians say that thousands of women marched with the mourners on that day, their arms full of flowers. As the parade entered the graveyard, both the children and the women laid flowers on the graves.

One newspaper reporter who witnessed the event wrote that “the holy mounds, the tops, the sides and the spaces between them -were one mass of flowers, not a speck of earth could be seen; and as the breeze wafted the sweet perfume from them, outside and beyond, to the sympathetic multitude, there were few eyes among those who knew the meaning of the ceremony that were not dim with tears of joy.”

Masses of flowers laid on the graves of those who died for their country were a part of all ceremonies then, in both the North and South, past and present. Along with the parades, the flags, the service people in uniform and the marching bands playing patriotic songs, there are always flowers.

I remember them well. My memories of flowers and Memorial Day take place in a small upstate NY village called Gilbertsville, where I grew up. Celebrating the village’s war dead was as sacred a tradition as those commemorations taking place at Arlington Cemetery, and throughout the country. And there were always flowers.

Lilac time in Gilbertsville always came around Memorial Day, one of the town’s most important holidays. Every Memorial Day a parade was held that marched through town. The high school band played, the Girl and Boy Scouts, 4-H clubs and the Grange marched, as did the members of the fire department and the American Legion. As a World War II vet, my Dad was a member of that group.

Behind the Presbyterian church was a hill with the Dunderberg Creek running at its base. This high ground was home to the village’s Brookside Cemetery. A narrow road, not much more than a wide pathway led up to it, and every Memorial Day the entire parade, as well as many of the townspeople, made their way to the back of the church and up to the top. This was the most direct route up there. There was also a paved road that was accessed further out of town, but that would have been a much longer and harder march.

The cemetery was dedicated in 1868 and was home to many of the old founding families and their descendants, and hundreds of Gilbertsville residents from the last 150 years. Many of the residents of the cemetery were veterans, with representatives of the Civil War, both World Wars, Korea and Viet Nam interred there. Today, with little peace in the world, there are no doubt those who gave their all for their country in conflicts that occurred after my time in Gilbertsville. All the veteran graves were marked with small American flags. Flags and lilacs.

Hundreds of branches of lilacs had been brought to the cemetery by families all around town, from the village and the surrounding farms. It was a coordinated effort of some organization or church, I never knew who. Bouquets of lilacs of all colors were placed at the graves of veterans. Family members following behind the parade carried more lilacs for their loved ones, veteran or not.

As the crowd stood there, prayers for the dead were said, followed by a 21-gun salute by members of the American Legion. The acrid smell of cordite was in the air, but soon overpowered by the pervasive scent of thousands of individual lilac flowers. The ceremony ended with the poignant echo of two coronets sounding “Taps.” One player stood on the hill near the crowd, the other halfway down the road back to the village. “Day is done,” the horns announced. “All is well, safely rest, God is nigh.” The notes were carried aloft by the wind, a call to those who went before, in battle and in peace, accompanied by the wonderful smell of lilacs.