Education

The Urgency of Anti-Racist Classrooms

by Eric Duncan,

Education Trust

“For too long, students have attended classrooms that gloss over our nation’s history with race…the responsibility for developing #anti-racist classrooms falls on everyone in the education system,” writes @ericduncan211 on @edtrust’s #TheEquityLine blog.

The deadly attack on the U.S. Capitol should be taught in social studies classes for many years to come. But the way it’s taught will be a test of whether America can finally reckon with racism or if it will continue down the path it’s been on for centuries — a path where we simplify a story of racism in our country and repeat a pattern of behavior that leads to the horrific events of January 6, 2021.

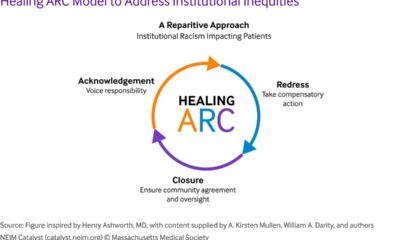

Now is the time to fully adopt anti-racist education. America’s children deserve an education that critically examines the role and actions of all citizens in maintaining and perpetuating a system that leads to a horrible moment in our history. In anti-racist classrooms, educators teach the lesson that we all have a role, every single day, to make sure that these events do not repeat themselves. From the people who ignore racist comments by their friends, to the senators and representatives who vote to maintain systems of racism, to the law enforcement agencies that treat peaceful protests of people of color as threats but allow White violence to go unchecked, we are all accountable for the conditions that led to the attack on the Capitol.

Consider the story of Emmett Till’s death. Here are two versions of this same historical event taught in social studies classes across the country:

In 1954, a Black boy from Chicago, unfamiliar with Jim Crow laws, was visiting his relatives in Mississippi, when he cat-called a White woman in a local convenience store. Some of the relatives of the White woman were enraged by his disrespect, kidnapped him from his relatives’ home, tortured him for hours, and brutally murdered him. The heinous act perpetrated by these southern racists shed light on the brutality of segregation in the Deep South and led to the Civil Rights Movement, ending the Jim Crow era in America. The end.

Another version includes this:

“I like niggers — in their place — I know how to work ’em. But I just decided it was time a few people got put on notice. As long as I live and can do anything about it, niggers are gonna stay in their place. Niggers ain’t gonna vote where I live. If they did, they’d control the government. They ain’t gonna go to school with my kids. And when a nigger gets close to mentioning sex with a White woman, he’s tired o’ livin’. I’m likely to kill him. Me and my folks fought for this country, and we got some rights.”

This is a quote from J.W. Milam in a national magazine article, written just one year after the murder to which he confessed every detail of the crime that he and his brother-in-law, Roy Bryant, committed against a 14-year-old Till.

The first version of the story of Emmett Till is appealing because it is sanitized, helping us avoid the complicated reality of racism in our country and its impact on our social order. It glosses over J.W. Milam’s mindset and rationale for committing the crime. While Milam’s language is offensive,* it reveals that this wasn’t just an act of a couple of racists who in a fit of rage snapped at a sign of disrespect — this was about a working-class citizen who didn’t like a perceived threat to his way of life and felt entitled to take matters into his own hands.

Sound familiar?

The second version of the history lesson, in all its vulgarity, examines the role and intent of multiple people involved in the crime: the White jurors who acquitted the men in the face of overwhelming evidence; the White woman who exaggerated Emmett Till’s actions knowing how it would affect him; the White citizens of Mississippi and people across the country who read the graphic confession and sat silent in acceptance; the dehumanizing rhetoric of the murderer explaining with pride that he was putting a Black person in his place and maintaining social order.

For too long, students have attended classrooms that teach the first version and gloss over our nation’s history with race and the role it played in the country’s current struggles with structural and systemic racism. We can attribute much of this to a long-standing lack of representation of educators of color in the classroom and in positions to influence curricula, teacher preparation standards, and instructional materials. But the responsibility for developing anti-racist classrooms falls on everyone in the education system: College teacher preparation programs must prepare prospective teachers to lead anti-racist classrooms; states and districts should design professional development for current teachers on anti-racist practices and classroom instruction; and all current teachers must seek out materials to deepen their knowledge and capacity to practice anti-racism in their lives and with their students.

If we want to position America’s next generation to learn from our country’s past mistakes, schools must teach students about the attack on the Capitol with this in mind. They must teach the version that includes the rhetoric of the people who commit acts of violence and abuse against those who they perceive as threats to their way of life. The version that critically examines the people around the perpetrators who fail to consistently hold them accountable for their words or bring them to justice for their actions. The version that teaches children that words used to dehumanize people like “niggers” or “illegals” cannot be ignored or else they’re used to justify inhumane acts of violence and terror like separating young kids from their families and holding them in cages.

Teaching an honest history of America’s issues with race is an important step toward dismantling systemic racism. For these lessons to take place, we need teachers who have the skills and dispositions to create safe spaces for students to critically examine and commit to changing our behaviors. We need to empower a more diverse workforce of teachers who are anti-racist in practice. The curricula, textbooks, and online materials in all schools must reflect the anti-racist principles that America purports to represent but has failed to follow. If we don’t commit to this path, our next generation is doomed to repeat our mistakes.

This article written by Mr. Duncan was originally published by The Education Trust on January 21, 2021.

*Editorial Note: The Education Trust’s policy is to avoid reprinting offensive language unless there is an extremely compelling reason to include it. In this case, we include it in support of the author’s compelling appeal to confront (and not sanitize) our country’s complicated racist past. The Education Trust is a national nonprofit that works to close opportunity gaps that disproportionately affect students of color and students from low-income families. Through our research and advocacy, Ed Trust supports efforts that expand excellence and equity in education from preschool through college, increase college access and completion particularly for historically underserved students, engage diverse communities dedicated to education equity, and increase political and public will to act on equity issues. Edtrust.org

Eric Duncan is a P-12 data and policy senior analyst at The Education Trust. He specializes in policies related to educator quality and increasing the racial diversity of the educator workforce.

Eric previously was a state policy advisor at WestEd, where he supported the organization’s federal and state policy strategy. Prior to that, Eric worked as a senior program associate at CCSSO, where he supported state efforts to diversify the teaching workforce and ensure that teachers are culturally responsive in practice through the Diverse and Learner-Ready Teachers Initiative.

He also worked as the director of district initiatives at the National Council on Teacher Quality, where he supported the development of a student teaching project with three large school districts across the country and led the organization’s communications efforts to promote evidence-based teacher quality research. Before that, Eric worked at the U.S. Department of Education, Office of the Secretary, as a LEE public policy fellow. He was a member of My Brother’s Keeper Task Force and supported the Department’s work on teacher diversity. Eric started his career in Atlanta as a high school social studies teacher. He received his undergraduate degree at Emory University and has a juris doctor from Wake Forest University.