News around the Web

Legacy Discussion at Washington D.C. Masjid

by Q. Daawud Grey,

The Internet Reporter

Age and affiliation of the participants in a recent panel discussion appeared to be major factors in assessing the legacy of three famous African–American leaders.

On June 3 at a Washington D.C. masjid, a panel of four African-Americans—three Muslims and one non-Muslim—briefly discussed the legacies of Elijah Muhammad, builder, and leader of the black social reformist group, the Nation of Islam; Malcolm X, former NOI spokesman and assassinated human rights defender, and Wallace D. Mohammed, America’s most influential Islamic thinker, and leader.

However, the age and affiliations of the speakers seemed to significantly shape their perceptions of the leader’s legacy.

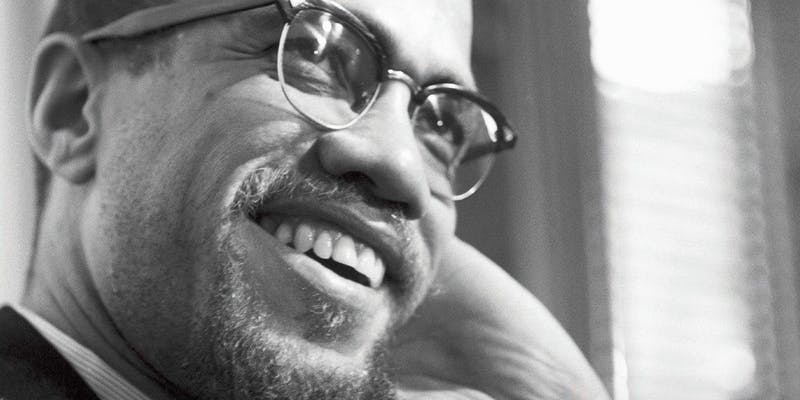

“To me, Malcolm X was a great human being, a great black man, and a great Pan–Africanist,” stated retired journalist and author, A. Peter Bailey, 85, the oldest of the four panelists. The other panelists were Dr. Talib M. Shareef, imam and president of Masjid Muhammad in Washington D.C.; Ibrahim Mu’Min, social activist and member of the masjid’s board of directors; and Shareef Abdul–Malik, entrepreneur and founder of the online marketplace,

Mr. Bailey, the first speaker to address the audience of about 50, said he believed “the only way” for people of African descent to overcome Aryan white supremacy and Euro–American racism is by practicing “Pan–Africanism.”

A year before his assassination, Malik El-Shabazz or Malcolm X (1925-1965), along with Mr. Bailey and others, formed the Organization of Afro–American Unity, a Pan–Africanist organization.

Pan–Africanism, as an idea, was born in the 19th century, out of a natural, human response to chattel slavery and European colonialism. It evolved into a racial ideology and worldwide movement, based upon a belief that peoples of African descent “share . . . a common history (and) a common destiny,” according to the online encyclopedia, Wikipedia.

Wearing a T–shirt with Malcolm X’s facial image on the front, Mr. Bailey said he was not a Muslim; had “no knowledge” of the organizations headed by Elijah Muhammad (1897-1975) or his son, Wallace D. Mohammed (1933-2008); and therefore, could not comment on their legacies.

The two–hour panel discussion, entitled “Transferring Legacies,” was sponsored by the masjid and the AbuSulayman Center for Global Islamic Studies at George Mason University. The moderator was Dr. Aminah McCloud Al-Deen, director of the center’s Black American Muslim Internationalism Project.

Each panelist was allotted 10 minutes and the youngest, Shareef Abdul–Malik, 31, spoke immediately after Mr. Bailey.

In defining the word “legacy” as “something we pass down to the next generation,” Mr. Abdul–Malik suggested that some ideas, associated with Malcolm X, should not be passed down.

“We should really consider what is important to pass on because not everything should be passed on to the next generation” explained Mr. Abdul–Malik, implying that “Pan Africanism” was one such legacy.

Meanwhile, Imam Shareef, 61, was convinced that there was one crucial legacy or “inheritance” which had not been passed down to the present generation and should have.

And that “inheritance,” representing the “hopes, dreams and vision” of all the past leaders, is the establishment of community–life among African–Americans.

“All of those who came before—Malcolm X, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the Hon. Elijah Muhammad, Noble Drew Ali, Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington—were addressing the needs of our community,” Imam Shareef pointed out. “They weren’t just talking; they were doing things in (and for) the (African–American) community.”

“But today,” the imam said regretfully, “we have gotten away from doing things collectively, as a people.”

The fourth speaker, Ibrahim Mu’Min, 75, the second oldest panelist, seemed to exemplify, based on his slide presentation, the community–focused, individual that Imam Shareef was alluding to.

For his 10–minute segment, Mr. Mu’min showed slides, documenting 50 years of community service which included: membership in the NOI where, in 1973, his first assignment was “assistant FOI (Fruit of Islam) secretary”; support for programs under the leadership of Imam Mohammed, such as the “New World Patriotism Day”; involvement with civil rights leader and Pan–Africanist, Stokely Carmichael, aka Kwame Ture, in support of Palestinian rights; collaboration with Catholic Archbishop Wilton D. Gregory of D.C. who became the first African–American cardinal; participation in the 2022 re–election campaign for U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock of Georgia; and participation in several gun violence protests.

However, only Mr. Abdul–Malik, the panelist of the millennial generation, specifically addressed Imam Mohammed’s legacy.

“The transferring of legacies for our (Muslim) community is best seen in the knowledge that was passed on to us (from Imam Mohammed)—the knowledge (and proper understanding) of the Qur’an,” he declared.