Black History

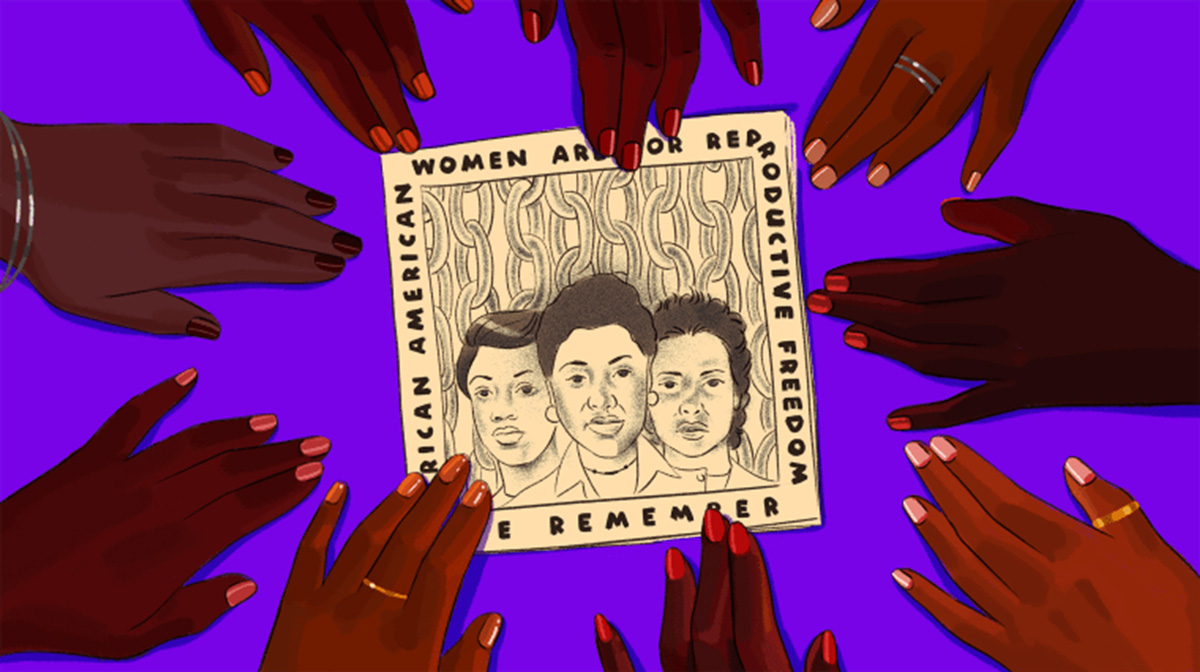

How this brochure sparked the movement for reproductive freedom

Black women and the fight for abortion rights:

By Natelegé Whaley

NBC News

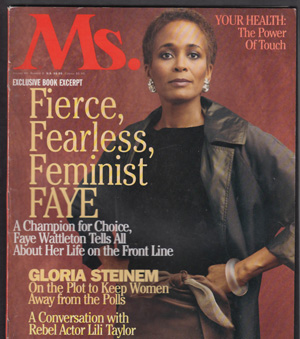

Faye Wattleton, the first black woman to serve as president of Planned Parenthood, stood on the steps of the Supreme Court in the summer of 1989 to condemn its decision on the abortion rights case Webster v. Reproductive Health Services. The high court had ruled that states had the right to limit abortion access.

‘’This Supreme Court decision once more slaps poor women in the face and says you do not have constitutional protections if your state sees fit to restrict them, and you do not have the resources to circumvent those restrictions,’’ Wattleton said, according to a New York Times report from August 1989. ‘’The court says certain fundamental protections that are part of your human dignity and part of being a respected and decent human being are not yours.’’

The Webster decision upheld a Missouri law that restricted state funded abortions at public facilities and public employees from conducting abortions, prohibited counseling in support of abortion, and stated doctors were to conduct viability tests for the fetus when a woman was 20 weeks pregnant or longer. Opponents of the ruling saw this as a threat to the 1973 landmark decision in Roe v. Wade, which affirmed that access to safe and legal abortions is a constitutional right.

Wattleton and other black activists, lawmakers and civil rights icons were fed up with the new debate about women’s right to choose. Largely, the voices of black women had been left out of the conversation around abortion access.

Until the summer of 1989.

That year, 16 black women made history by publishing the first collective statement advocating for equal access to abortion, “We Remember: African-American Women are for Reproductive Freedom.” Retired U.S. Rep. Shirley Chisholm, soon-to-be-elected U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters and civil rights activist Dorothy Height were among the notable names who signed the unprecedented brochure. Many points in the pamphlet amplified some of Wattleton’s statements that day in front of the Supreme Court.

“Now once again somebody is trying to say that we can’t handle the freedom of choice,” the document said. “Only this time they’re saying African-American women can’t think for themselves and, therefore, can’t be allowed to make serious decisions. Somebody’s saying that we should not have the freedom to take charge of our personal lives and protect our health, that we only have limited rights over our bodies.”

September marks 30 years since the statement was first distributed, at anti-apartheid demonstrations, anti-rape rallies and other public venues. In commemorating this public statement, there are some parallels to the state of abortion access in today’s America. Under the Trump administration, reproductive health advocates say Roe v. Wade could be overturned which, experts say, could have devastating effects for low-income women of color. As of 2014, black women are 28 percent of those who sought abortions, compared to 36 percent of white women and 25 percent of Hispanic women, according to the Guttmacher Institute. Meanwhile, 60 percent of black American adults say abortions should be legal in all or most cases, according to a Pew Center Research report in 2018.

It was against a similar backdrop that black women banded together to create the “We Remember” brochures. Ordinary black women who felt ashamed to discuss their abortions publicly now had the support of some of the most powerful black women in the country. The brochure supported their rights to have complete ownership over their bodies and addressed how racism and poverty also impacted those decisions.

“We, black women, who have been very active in reproductive politics for a long time felt like we were leaders without a constituency,” said Loretta Ross, a professor at Arizona State University in Phoenix, an organizer of the brochure and co-founder of the reproductive justice movement in 1994. “We represented the black women who walked into the clinics, but no one had given them permission to own up to what they were doing. They were speaking with their feet rather than with their mouth.”

Following the Supreme Court ruling, Donna Brazile, a founding member and organizer with the National Political Congress of Black Women, arranged a conference call with prominent black women including Ross, then-director of the women of color program at the National Organization for Women, and Byllye Avery, founder of the National Black Women’s Health Project, which is now the Black Women’s Health Imperative.

The National Political Congress of Black Women and the National Coalition of 100 Black Women were among the few black women’s organizations who spoke out proactively on abortion rights, according to Ross.

“A number of them spoke out, but you had to persuade them because they were afraid of alienating what they perceived as their religious membership,” the activist said. There was also the stigma that supporting the right to abortion meant supporting black genocide. Not everyone who was on the call signed the document, Ross explained.

Avery, who Ross described as having the strongest standing in the reproductive freedom movement in the black community, suggested the group write a pamphlet, the most common form of distributing new ideas in the public forum in the era before political hashtags spread the word about campaigns. The pamphlet would act as a permission slip to speak out about abortion access, Avery argued, as many leaders were afraid to be punished by their constituencies for supporting the right to choose.

Faye Wattleton was the first African American and the youngest president ever elected of Planned Parenthood Federation of America, and the first woman since Margaret Sanger to hold the position. She is best known for her contributions to family planning, reproductive health, and pro-choice activism. As a nursing student at Columbia University, Wattleton saw a woman die of a botched abortion. She came to understand that the fight for safe and legal abortions was also about the fight against racism, sexism and poverty. According to an article in the Baltimore Sun (1990), “In 1989, after the Webster vs. Reproductive Health Services decision handing states the right to limit abortions, Wattleton told a crowd on the Supreme Court steps, ‘This decision once more slaps poor women in the face and says you do not have constitutional protections if your state sees fit to restrict them and you do not have the resources to circumvent those restrictions.’ “

The Baltimore Sun reporter wrote, the United States must re-educate itself before it can correct its confusion about sex (a recent national survey reported widespread ignorance on basic questions about sexuality), the crises of sexually transmitted diseases, and a soaring birthrate among poor, young women, Wattleton says. “That means a very radical change in the way we see ourselves, but also in the way we see our children and their sexual development. The lack of comfort with sexual matters on the one hand, the spread of explicitly sexual materials and ideas at the same time we repress knowledge and information, I’m sure, from some one’s point of view of looking at us from afar, is peculiar indeed,” Wattleton says. “But I think it really does reflect the vestiges of our puritanical traditions, which were by the way, pretty hypocritical even back then . . . We have a tragic record to show for it.”