Arts-Theater

The Renaissance of Sculptor Augusta Savage

By Fern E. Gillespie

Although the great sculptor Augusta Savage was a pivotal force in the creation of the Black fine arts movement of the Harlem Renaissance era, for decades she was a footnote in Black History.

No more.

There is currently a renaissance swirling around her and her work. Most notably, during this February and March, Augusta Savage’s milestone cultural impact has been celebrated through a major PBS documentary, the Metropolitan Museum of Art Museum exhibition, a multi-faceted 3D education program, and the creation of a new department at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., devoted to the artist’s life and work.

Art historian Dalila Scruggs has been appointed The Smithsonian American Art Museum’s first curator of African American art with the position Augusta Savage Curator of African American Art. It was created through an anonymous $5 million endowment gift to the museum in honor of sculptor Augusta Savage.

The PBS American Masters documentary Searching for Augusta Savage, available online, is directed by Charlotte Mangin and Sandra Rattley and narrated by art historian Jeffreen M. Hayes, Ph.D., who curated the touring exhibit Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman from 2018 to 2020. The documentary explores Savage’s life and legacy, and why her artwork has been largely erased.

At New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, audiences have been thrilled by the groundbreaking Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism exhibition. Under the direction of MET curator-at-large Denise Murrell, a popular piece is Gamin’, Savage’s historic sculpture of her nephew on loan from Schomburg.

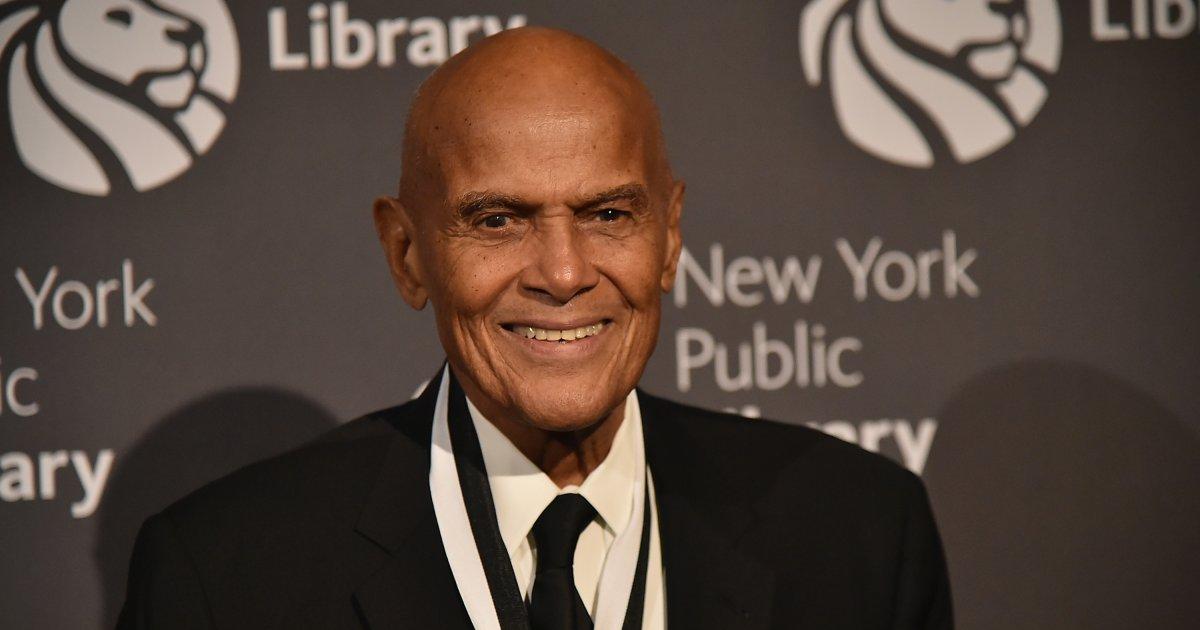

At the center of this Augusta Savage whirlwind is Tammi Lawson, curator of Arts & Artifacts at the Schomburg. Lawson, who holds a master’s in library science from Queens College, has worked at the Schomburg since 1989 and joined the Arts & Artifacts Department in 2013. Since 2018, she’s led the department as curator.

She’s been the touchstone with all of these Augusta Savage projects including the award-winning young adult book by poet Marilyn Nelson, Augusta Savage: The Shape of a Sculptor’s Life, for which Lawson wrote the afterward.

“I’m always pushing Augusta Savage. She’s remarkable. Her story should be told because there’s no artist like her. She was intentional with her work and her vision,” Lawson told Our Time Press.

Augusta Savage (1892 – 1962) was born Augusta Fell in Green Cove Springs, Florida, the seventh child of 14 children. As a child, she would sculpt animals from red clay found in the area. In the 1920s, she ventured to New York City to study art at Cooper Union. Although she received financial support from the college, she still had to work as a domestic to support herself.

By 1923, Savage received a summer scholarship to the prestigious Fontainebleau School of Fine Arts in France. The award provided travel and study for 100 women artists. However, when the school discovered she was Black, the offer was rescinded. There was an uproar from the Black arts community, including WEB DuBois. In 1929, her famed bust of a Black boy, Gamin’, earned her a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship to study in Paris.

August Savage was the first African American artist elected to the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. In 1932 she opened the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts and in 1935 became a founding member of the Harlem Artist Guild.

Then, in 1937, she helped establish and was the first director of the Harlem Community Art Center, which received funding from the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which was instrumental in nurturing some of the Harlem Renaissance’s most famous artists.

“At the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts, she taught the kids and when they learned enough she was able to hire them as teachers. Then the WPA came along and she was made Director of the Harlem Community Art Center.

She took her students with her,” explained Lawson. “Along with Mr. Schomburg, Norman Lewis, Charles Alston and others, she started the Harlem Artist Guild, which fought for Black artists to be put on WPA projects. Those same students, who became teachers now became directors of the mural project at Harlem Hospital.”

Augusta Savage was an artist, activist and administrator who was about getting jobs for Black artists. “During the latter part of the 20th century, a lot of the artists went on to be famous like Norman Lewis, Jacob Lawrence, Selma Burke, Ernest Crichlow and Bob Blackburn,” said Lawson. “They all owe a debt to Augusta Savage. They all say she was instrumental in their careers.

Jacob Lawrence has said he wouldn’t be an artist if it wasn’t for Augusta Savage, because she actually took him down to the WPA and had him sign up. She told him ‘you should be paid for the work that you do. You are an excellent artist.’ He would not have done that. He said that. She’s remarkable.”

In 1939, she had two career milestones. She opened the Salon of Contemporary Negro Art, the first gallery in the United States dedicated especially to exhibiting and selling works by African American artists. That same year, her magnificent, monumental 16-foot sculpture Lift Every Voice and Sing, was exhibited at the 1939 World’s Fair.

The harp-shaped sculpture featured faces of actual Black models, including the father of the Schomburg’s former curator George Murray. Tragically, it now only exists in photographs and miniature sculptures. It was destroyed.

“While it was on display it was part of the design commission for the World Fair. When it was over, the artist could take their work back. But there was a deadline. So, if you didn’t get your work by the deadline it would be removed,” explained Lawson. “In her case (it was) demolished because it was so big. It was 16-feet tall. Fisk University had an interest and also an insurance company in Florida.

She not only did not have the money or storage to have it moved from Queens. Then it would have to be shipped by boat or whatever to Florida or Tennessee. She did not have the money. By the time they expressed their interest, it was past the deadline.”

Augusta Savage was married three times and she had a daughter. Her last husband was Robert L Poston, a journalist and Secretary-General to Marcus Garvey, who died in 1924. By 1945, Savage left Harlem and moved to a farmhouse in Saugerties, New York.

She developed a new science career in STEM. While still creating artwork, she worked as a laboratory assistant in cancer research.

Through her step-granddaughter, Lorraine Lucas, Augusta Savage’s legacy continued at Harlem’s Schomburg. “Lorraine Lucas donated most of the artwork that we have in our collection,” said Lawson. “She knew that Augusta Savage’s daughter Irene wanted them to come to the Schomburg. Lorraine lived in Brooklyn and she was part of Harlem’s honey and bears swim team for seniors.”

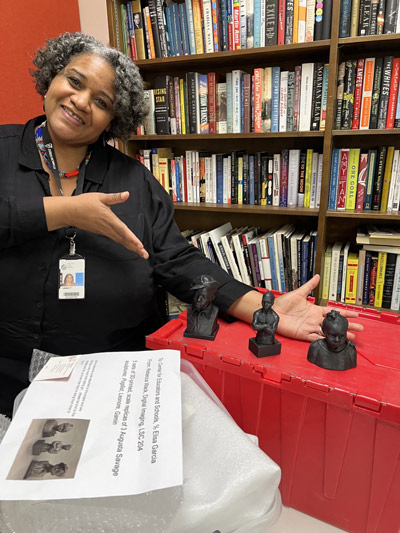

This month, Lawson headed a project that gives students a hands-on touchy-feely experience of holding August Savage’s sculptures. It’s 3D statues and curriculum created through a collaboration between The New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, NYPL Digital Imaging Services and the Center for Educators and Schools.

The interactive set features 3D-printed replicas of original artworks by Augusta Savage from the Schomburg’s Art and Artifacts Division at the Schomburg Center. The set includes laminated photos of Savage at work at the Schomburg and multiple copies of poet Marilyn Nelson’s young adult book “Augusta Savage: The Shape of a Sculptor’s Life,” a young adult book that tells the story of her life in poems and photographers with an afterward by Lawson.

“We are so excited to share this new interactive teaching resource as it continues Savage’s legacy as an educator and provides students the opportunity to personally experience her artwork through the use of 3D printing technologies,” said Kimberly Henderson, Digital Curator, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, who headed the Schomburg’s involvement with Lawson.

“These stunning 3D printed replicas of original artworks by Savage give students the chance to learn more about the artist while interacting with a replica of her work. It also welcomes them to visit and explore the collections at the Schomburg Center, which holds the largest public archive of Savage’s work.”

This tool is available as a Book Club Set from MyLibrary, a program that offers more than 10,000 Teacher Sets from NYC public libraries.

“This is Black Girl Librarian Magic!” said Lawson. “Now we are doing what Augusta Savage wanted us to do. She said: ’If I can instill something in these children and bring out the talent I know they possess, that’s my legacy.’ So, I feel that I am advancing the legacy of Augusta Savage.”