Arts-Theater

Jeffery “Kazembe” Batts Connects Hip Hop and Marcus Garvey

Raised by a single mother in Bedford Stuyvesant, Kazembe Batts is one of those quiet presences who has always been there, working in the trenches whenever progress has been made on the African American road to freedom.

A Hip Hop enthusiast and an adherent to the Pan-African philosophy of Marcus Garvey, at this 50th anniversary of Hip Hop, and the beginning of Black August and the celebration of Marcus Mosiah Garvey’s 136th year, we asked Kazembe how did his activism begin and what he sees as the present state and future of Africans in America and around the world.

Early in his education, he was bussed to Mark Twain JHS in Bensenhurst and later attended Boys & Girls HS, going through the CUNY system and receiving his Bachelor’s and Master of Arts in Urban Studies from the School of Professional Studies at the Graduate School & University Center at CUNY in January 2017.

Stevie Wonder was his favorite artist, particularly the Key of Life album, and later Hip Hop, frequenting clubs in Manhattan and Brooklyn, listening to artists like Dougie Fresh, Special Ed, Grandmaster D from the Roosevelt Houses and attending performances at St John’s Park, 258 Park, and the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, being particularly drawn to the artists who were political with their music. “I grew up in the culture and lifestyle. Back in the day, unlike the music you hear on the radio now, it was political and I was political as I became an activist as a young person. Whether it was KRS1 who talked about Kemet and other aspects of ancient African history, or whether it was Sonny Carson’s son, Professor X, who was the first grand Marshal of the Universal Hip Hop Parade, or Sister Souljah, that influenced me in a big way because this was what I was looking for, it was inspirational, talking about black power and the need for us to be organized and to resist White oppression and White supremacy. Being able to hear it on the radio from people who were accessible since they were from the neighborhood. This was before artists made as much money as they do now. They were more accessible.”

However, Kazembe acknowledges that all of Hip Hop was not political. “There was the party side, there was the sexual side coming out of Florida but as an activist, I really went towards the pro-black and uplifting side of the culture and the music in particular,” always overlapping his activism with Hip Hop.

Kazembe’s activism had a very personal starting point. One of his best friends was Artie Miller, the son of Arthur Miller, the businessman and community leader choked to death by police in June of 1978.

“I used to take the school bus to the White area of Bensenhurst. The whole system had buses taking us out there. The Millers lived in Crown Heights and I lived in Bedford Stuyvesant but we took the same bus.”

He remembers coming home on the bus with Artie and his sisters crying because their father had been murdered. “I was 13 and I never forgot that. That sat with me a little bit but then a few years later Michael Stewart was murdered and by then I was like 17 or 18” at which point he became involved with the Michael Stewart Justice Committee with Charles Barron which was based at the House of the Lord Church. “We didn’t get justice for Michael Stewart as in so many other cases and I haven’t stopped organizing since.”

It was while he was an intern at the Arthur Young accounting firm, that he had a Park Avenue lunchtime conversation with a Hasidic Jew who was telling him about Israel and the oppression of the Jews. In the exchange, Kazembe said he was really concerned about what was happening in South Africa. “And I’ll never forget the way he looked at me and said, ‘you’d better.’ That always stuck with me. That was when Mandela was still in jail and apartheid was strong and P. W. Botha seemed invincible. The way he looked at me and said ‘You’d better,’ I got more involved in the anti-apartheid movement and that started my more international perspective on struggle and I discovered Garvey who was a Pan Africanist and global in his impact.”

Kazembe sees the “blatant” upsurge of White supremacy and finds it surprising that it is worse than when he was coming up, encouraged by Donald Trump and others like De Santis in Florida. He is concerned that with the gentrifying of the neighborhood, “we really don’t know what percentage of these newcomers to our neighborhood, living right next door, might have that White supremacist mentality.”

His further concern is that when elections come, “They might be able to significantly swing the type of representation we have if not even electing one of their own.”

His exposure to Garvey deepened after a rally he attended that Minister Louis Farrakhan held at Herkimer and Nostrand for the Nation of Islam where he spoke not only about the Nation but also about Marcus Garvey. Kazembe was very impressed with what was said about Garvey and his holistic approach to the Black struggle as being political, economic, and spiritual. “Garvey had his newspaper in three languages, English French, and Spanish, he had global influence with chapters in Cuba and South Africa. I hadn’t really learned anything about him in school and it was like once I did start learning about Garvey he just seemed so impressive.”

Opportunities to about Marcus Garvey and Black history in general have become an issue across the country with the banning of books and the attempts at revising history to the point of saying that slavery was an actual benefit to the Africans held in bondage. This is a position that recent polls show the majority of Republicans hold to.

Looking at the curriculum changes happening in Florida, Kazembe says of Republican presidential candidate Florida governor Ron DeSantis, “DeSantis is anti-Black, it is what it is. Call things for what they are.

He’s using his power trying to divide and conquer people of color.” Kazembe points to how DeSantis “went out of his way to encourage” challenges to Affirmative action and Critical Race Theory and it was “just a part of his White supremacist agenda.”

That agenda includes rolling back the ability of ex-felons being able to vote and voter suppression in general. “He’s doing everything he can to disempower Black people. This is not complicated or hard to figure out. There are people who don’t like us and when they have power they use their power to try to keep us down.”

Closer to home, what’s happening in Brooklyn that gives him cause for concern is gentrification and the loss of property and institutions where Black people can meet and talk about their concerns. He cites the Slave Theater as an ultimate example of a powerful space in central Brooklyn to speak to the Black struggle that’s been lost and churches that are being lost. “That’s why it’s so important that we save Magnolia Tree Earth Center as a Black institution. We don’t have too many places where we can go to sit around Black people and talk about power.” He mentions Sista’s Place at Nostrand and Jefferson as one such place, but laments that there aren’t others that he is aware of.

He notes that central Brooklyn has one of the largest concentrations of Black people but notes that it’s said that the percentage of black people is down to 49% given the large influx of Whites. “Sometimes I stand on Nostrand and Fulton and watch people coming out of the subway and there would be more Whites than Blacks coming out. Maybe they go to their jobs and come back and we just stay in the neighborhood.”

“When this was a solid black community at least you could look around and see your own people and feel a sense of security. But nowadays you don’t know who’s walking around or what

Kazembe Batts

they’re thinking. Many of them speak different languages like they just got off the plane from Europe and you don’t even know what they’re saying. Things like that trouble me as a Pan-

Africanist.”

Looking around the neighborhood, Kazembe sees White-owned businesses open and immediately begin flourishing, “I don’t know if White people have a network, maybe through social media, when they automatically go to patronize and make sure they sustain,” while Black-owned businesses pop up but seem not able to survive.

He sees property not being passed on to following generations due to weakness in the families, with folks losing properties or cashing out and moving down South. Regarding the many Blacks in political office, he says, “We have political black power everywhere as far as elected officials, but that doesn’t translate into power on the ground and there doesn’t seem to be a focus on maintaining and strengthening Black power in the community.”

Regarding the influx of immigrants to New York, Kazembe says he’s for immigration and “some of those immigrants are black people, even though they might not consider themselves Black, but even those that aren’t I welcome them. But I don’t welcome them ahead of the numerous Black homeless and shuffling along people I see on the streets every day as I walk around the community. I think there should be a focus on them as well as on the immigrants.”

Kazembe sees the “blatant” upsurge of White supremacy and finds it surprising that it is worse than when he was coming up, encouraged by Donald Trump and others like De Santis in Florida. He is concerned that with the gentrifying of the neighborhood, “we really don’t know what percentage of these newcomers to our neighborhood, living right next door, might have that White supremacist mentality.”

His further concern is that when elections come, “They might be able to significantly swing the type of representation we have if not even electing one of their own.”

“When this was a solid black community at least you could look around and see your own people and feel a sense of security. But nowadays you don’t know who’s walking around or what they’re thinking. Many of them speak different languages like they just got off the plane from Europe and you don’t even know what they’re saying. Things like that trouble me as a Pan-Africanist.”

Kazembe looks with a critical eye at all the political power in the community and fears real power, “people power,” is being lost. “That’s one of the reasons I’m a big Garveyite. He’s an example of unity and the principles of Kwanzaa that Maulana Karenga laid out. We need to have more unity and more boldness.”

Batts says he and his group recognizes that the Universal Hip Hop Parade is only one day, but at an organization meeting, one of the items spoken about was STEAM, which they interpret as Science, Technology Engineering, Activism and Militancy. And by militancy, they mean to be “bold and assertive in this age of White supremacy. Not to be moderate and compromising unnecessarily.”

After the parade, they want to build on their STEAM concept. Remembering that Garvey and others talked about Africans having the skills to build pyramids and in contemporary times “when you look behind the scenes they’re black scientists everywhere whether it’s in space or other forms of technology.”

(Were they to look further “behind the scenes” they would find and draw inspiration from Count C.F. Volney writing on ancient African civilizations in his 17th-century opus, The Ruins, or Meditation on the Revolutions of Empires and the Law of Nature

“There a people, now forgotten, discovered, while others were yet barbarians, the elements of the arts and sciences. A race of men now rejected from society for their sable skin and frizzled hair, founded on the study of the laws of nature, those civil and religious systems which still govern the universe.”)

“We have to boldly support our people getting the skills and using them to build ourselves up and not just to build the status quo and that’s the challenge I see today. And that’s why I go back to the principles of Kwanza, or the philosophy and opinions of Marcus Garvey, or the teachings of Malcolm X and try to put into practice unity and being able to boldly and proudly focus on ourselves. Not to impress others and not to be against a partnership with others because we are not on this planet by ourselves.”

“I often tell folks when they talk about White supremacy, and that’s a big problem, but anti-Blackness goes beyond that. Look at what’s happening in Darfur, where some look Black, but they have an Arab mentality and they’re committing genocide in Darfur.”

Kazembe cites other instances of anti-Blackness in Asia, and Latin America, “The Dominican Republic with their anti-Haitian anti-Black mentality there’s an anti-Blackness globally so it’s bigger than just white supremacy, it’s really Anti-Blackness and so Black people have to stick together and be more militant and assertive for our best interests.”

In this presidential election season, Kazembe would like to see a Black-centered foreign policy asserted. “All this money for Ukraine and a lot of people still can’t find Ukraine on the map. All these billions of dollars and yet Haiti, so close, where the U.S. has had such a historical impact can’t get the support it needs, and not in a neo-colonial way. I’m talking about spending our tax dollars on resources for Haiti and the need for us to be supportive of what might work.”

Kazembe looks at how there are more Black people in America than there are in Russia or in China or in Turkey, India, or Israel, and yet some of these countries are trying to maximize their influence over the Motherland. “Although I definitely get why some folks on the continent would be against the United States being more involved however they have to recognize that in the tradition of Malcolm X or Paul Robeson, there can be independent Black thought on foreign policy. I would like to see us maximize that. I’m disappointed in the likes of Congressman Gregory Meeks and Hakeem Jeffries. They don’t seem to be able to articulate or be in sync with what’s really good in a global sense for Black people. They just fall in line with America’s foreign policy is often detrimental to Black people both historically, and here I’m thinking of Patrice Lumumba as an example, and others and contemporarily as well.”

Kazembe says that in the same way Blacks have changed domestic policy such as the laws mandating sitting in the back of the bus, we can strive to change foreign policy as well. “It’s a long and complicated process but I think it’s very important. I don’t want to just hear about Ukraine and Israel as in foreign policy discussions. Given the internet and the ability to travel around the world, we need to think globally in the tradition as exemplified by Paul Robeson and Malcolm X. We need to build on that and make it stronger for today. It seems that thought is so much weaker now and there’s no real leader in America that speaks for a pro-Black foreign policy like Malcolm did. We wear Malcolm X shirts and say we like Malcolm, but are we living it? I feel like we’re going backward.”

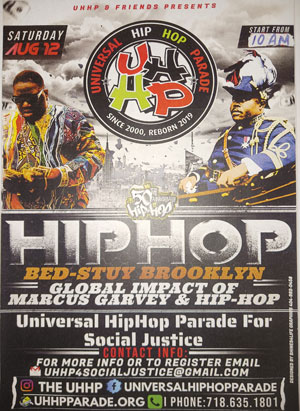

This is why the theme for this year’s parade is global impact. Both Hip Hop and Marcus Garvey have a global impact and that’s our theme for this year.”

The parade is Saturday, August 12th starting at 10:00 AM at Magnolia Earth Center, 677 Lafayette Avenue. “There’s a lot happening that day. A lot of people date the beginning of Hip Hop from the 50th anniversary of Cool Herc’s party in the Bronx on August 11th, 1973 and our parade is always the Saturday before Marcus Garvey’s birthday which is August 17th . We’re going to have a pre-parade brunch inside Magnolia and then we’re going to make our way down Marcus Garvey to Fulton St. and then down to where the Slave Theater used to be at Bedford Avenue. Uncle Ralph McDaniels has shown us a lot of love over the years and he’s going to be our Grand Marshal along with Dejay Hard-hittin Harry as well as legendary graffiti artist James Top and ‘King Up Rock’ Ralph Cassanova will comprise the four Grand Marshals. We’re having a little something at the Bed-Stuy Boxing Club along the route focusing on dance and graffiti.

Parade organizers want people to come out for both activism in general and Black power in particular. They’ve reached out to the Universal Negro Improvement Association, Garvey’s organization, the December 12th Movement, and the Nation of Islam on the movement side. On the Hip Hop side, they have None Stop Productions and other local artists. “We have the Loudmouth store which is a Hip Hop store on Marcus Garvey across the street from the Armory at Jefferson, where there will be a fundraising show on August 4th. We’re still grassroots and we don’t have a lot of corporate support and at some point, we want to change that.

“I was at the library the other day checking out what they did for Jay Zee and it was very impressive. I’m not mad at him although some people in the movement are, but I don’t mess with them. People work in different lanes so I’m not hating on him, in fact, I’m impressed with the exhibit. Sometimes we hope to be able to connect with the Shawn Carter Foundation among others. We’re keeping it Garvey and Hip Hop we call it a mash-up because they both have a global impact. It’s all about inspiring younger folks. As I get older I realize we want younger folks to pick up the banner and work for what our forefathers and mothers have been doing so we can survive as a people.”

People can contact us at UHHP4socialjustice@gmail.com