featured

An e-conversation launches a summer series, “The National Ecology Report.”

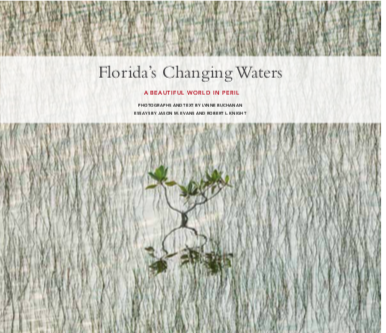

…Of Roots & Rivers

Bernice Elizabeth Green and Lynne Buchanan

This spring, photographer/essayist Lynne Buchanan and I have exchanged e-mails about America’s endangered rivers. We explored ways to get the word out to our respective publics about a challenge that may not appear to be as near to our lives as education, economics, housing, racism, and more. But, in fact, it is closer to our souls than we may know — as Native Americans, Africans and peoples of the indigenous worlds have always believed. We shared e-mails back and forth until I understood the message Our Time readers need to receive.

On these pages are Lisa Farrow and Lynne Buchanan’s images. Lisa, in New Jersey, and Lynne, in Florida, do not know one another. Buchanan’s mail has motivated me to become a RiverKeeper as much as I am a race woman. We introduce Lisa’s beautiful photo stills of what is, right now, as well as Lynne’s images and dispatches from Florida on a sickness that ekes its way into our lives, with poisons as deadly as the isms. This column will talk to artists and creatives around the nation against the backdrop of America’s changing scenery and landscapes as Lynne’s reports from Florida are featured on a recurring basis through the end of summer’. The following introduces the series, which starts next week.

Bernice Elizabeth Green: For many, living in or near the centers of cities, preserving waterways is not an issue that rests at the top of our mind. We may think of preservation as an agency of houses, forests, cultures. It is not as though you look out of your apartment window from your Eleanor Roosevelt Housing and see a river coursing west down DeKalb Avenue en route to Brooklyn Bridge Park and New York Harbor.

Lynne Buchanan: We all get our drinking water from rivers and springs, and all people eat food, whether they eat fish, livestock or are vegetarians or vegans. Everything needs water to grow and live. If animals drink impaired water, or crops are watered with it, that affects the health of the creature and fruit or vegetable. And when we consume them, we can also become sick. I live in the mountains of western North Carolina now and my water comes from a well. It’s pretty clean, because it is filtered through the mountains for a long time. The drinking water supply for Asheville is in a pristine area of the Blue Ridge, too. We are lucky.

People in NYC are lucky too, because their drinking water comes from the Catskills and is also relatively clean. Western North Carolina’s aquifer is comprised of separate pockets because of the mountains, so it takes a while for pollution to travel from one area to the next. However, in places like eastern North Carolina and Florida, the aquifer has no barriers and pollution from one area travels easily to the next. Rivers and streams that feed into major rivers cover the entire country, yet there are only 78 major watersheds and 5 major drainage areas.

If you look at the Mississippi Watershed, for example, you’ll see that it covers nearly a third of the country. There are many beautiful maps and when you look at them, you see that tributaries and rivers are like arteries and indeed they provide the lifeblood for our existence wherever you live. Yet, they are all connected, which also means that pollution does not stop at the borders of neighborhoods or states or even countries. And it doesn’t just stay close to the ground either. It evaporates and with airborne pollutants, falls down on the earth again in the form of acid rain.

BG: Why are rivers of fascination to you personally? Is there someone in your life, early on, who told you stories about ecosystems? What can we do to engage our children more?

LB: My father was a philosopher and he greatly admired Heraclitus, whose famous quote was: “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” I found this quote fascinating because it conveyed how life is always in flux. It also made me realize that water has no separate beginning, middle or end. It is all connected, and people are all connected. The “not in my backyard” concept creates a false sense of security. If you think a Superfund Site is in someone else’s backyard instead of yours, then you are not worried about what is being dumped into the water there, but it will affect that which you don’t anticipate.

(As an aside, this is also a human rights issue, as those who are forced to live a subsistence lifestyle due to poverty have to fish in the worst waters because they can’t afford boats or fuel to travel to less-toxic areas to get their food off of cleaner land.)

Though my father was not an outdoors person at all, he knew we don’t live outside nature and he was a firm believer in ethics. My father taught me to learn from everything, to ask questions and pay attention. When I kayaked on rivers growing up and for this project, I was always aware of the lessons they were teaching me. Rivers also teach us not to give up, especially when encountering snags (fallen trees) and other obstacles. You usually can’t just get out in the middle. You have to keep going, think outside the box, find a way around and through your troubles, and mostly endure. Speaking of endurance, what a great success the Maori tribe achieved recently when after 140 years of negotiation, they finally won recognition for the Whanganui River, which means it now must be treated as a living entity. The Maori are some of, if not the greatest water projectors in the world.