National News

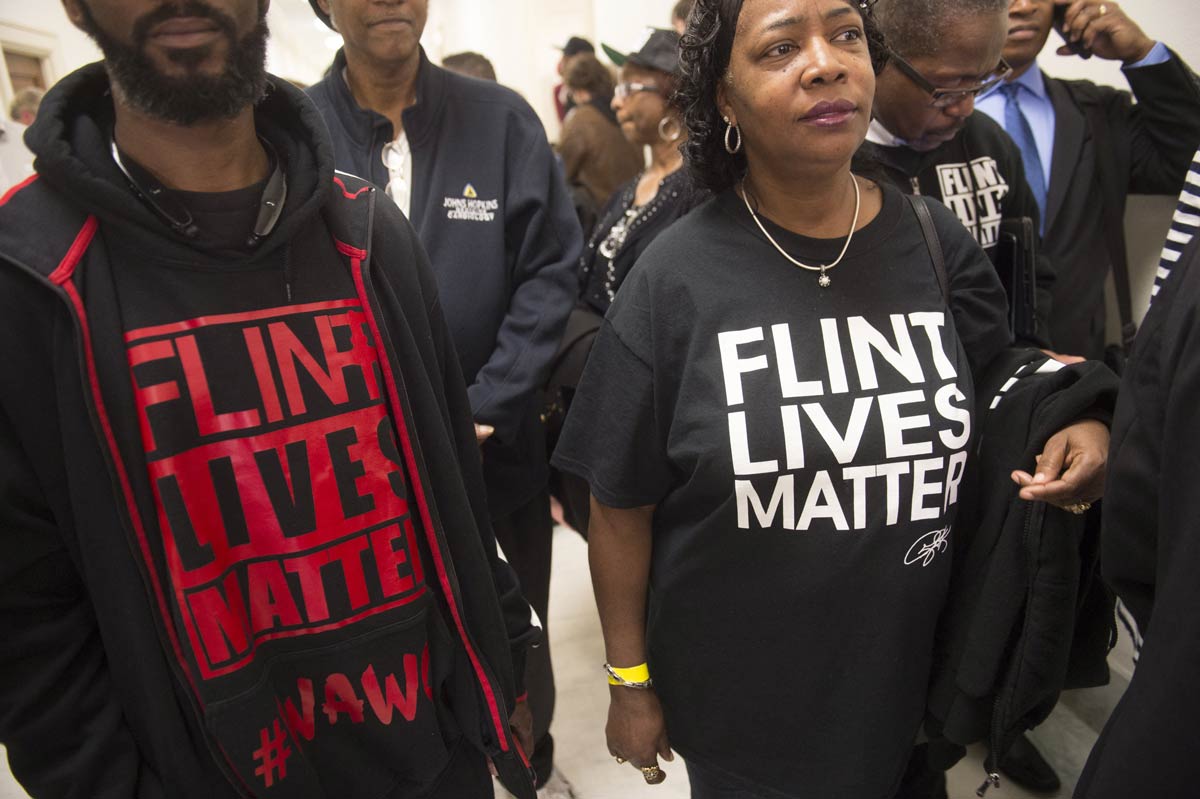

The Flint Water Crisis

by Nehemi’EL Simms

Among the environmental injustice issues facing this country is the growing national water crisis impacting cities throughout the nation related to access to fresh water.

Moreover, the recent U.S Census records show that this public health crisis is predominant in areas with mostly Black residents. Cities like Washington, D.C.; Houston, TX; Las Vegas, NV; Baltimore, MD; Jackson, Miss., and Benton Harbor, Michigan have been widely reported, but there is one city where it appears all issues have collected, making it the quintessential example of neglect: Flint, Michigan.

Flint’s problems began in 2014 when the city decided to redirect the source of its water supply from Lake Huron to the Flint River. The switch was declared a cost-reduction effort. Complaints mounted and became national about the foul smell, taste, and coloring of the water coming from kitchen and bathroom faucets, plus the rashes and loss of hair. Eventually, the Michigan State Civil Rights Commission determined that the government’s slow and pathetic response to the suffering community was a “result of systemic racism.” Then tests revealed that the contaminated water was attacking the health of children, and the blood lead levels were soaring.

According to the U.S Census, Flint, Michigan, is 56.7 % Black people; 12% of the population, above 25, has a bachelor’s degree or higher; and the median household income is $32,358 compared to $74,580 of the average American.

Flint, as a social phenomenon, perhaps, is best explained by the formerly Detroit-based scholar, “organic intellectual,” labor activist James Boggs (1919-1993), author of The American Revolution: Pages from a Negro Worker’s Notebook in 1963.

In Boggs’s essay, “The Myth and Irrationality of Black Capitalism,” he observes that “the physical structure and environment of the black community is undeveloped not because it has never been at a stage of high industrial development but because it has been devastated by the wear and tear of constant use in the course of the industrial development of this country.” This is consistent with the history of Flint—the birthplace (in 1908) of industrial powerhouse General Motors (GM).

A case study by Michigan State University entitled “Long-Term Crisis and Systemic Failure: Taking the Fiscal Stress of America’s Older Cities Seriously” traces the history of Flint’s social and economic standing to variables besides the booming automotive industry. For example, the study shows that the Flint River provided the “natural resources to create successful commerce” for markets like “fur trading, lumber, the manufacture of carriages and eventually the production of horseless carriages.”

Flint was what a MyCityMagazine article called “unstoppable in vision and immeasurable in charm.” However, by the mid-1980s, General Motors began to downsize, and by 2010, it had laid off 80,000 workers and closed several factories, which were important sources of middle-income salaries for the Black community.

What was once an affluent city, blessed with industrial vigor and an economy emanating from the Flint River, became, to quote Boggs, a community in “decay,” or ”the end result and aftermath of rapid economic development.”

Flint is still dealing with the ramifications of what President Barack Obama declared a national emergency. The legacy of the Flint Water Crisis is alive and well in the minds of natives who recall showering themselves and their children in lead-infused water.

Thirty-year-old Flint native Tarrell McDaniel, who has lived in the city since 1999, recalls the smell of rotting eggs and the sight of brown water from his faucet. McDaniel explained that in 2014, the city of Flint, $21 million in debt, looking to cut its budget, decided to change its water supply from the Detroit-supplied fresh-water Lake Huron, one of the five Great Lakes, to the Flint River.

“City officials decided to stop buying water from Detroit and switch to the water in the Flint River,” McDaniel said. “But everyone knows that the Flint River water is terrible. We find trash, dead bodies, and all kinds of other things in there.”

Tarrell’s lamentations of municipal negligence are matched only by his deep regrets concerning the lack of proactivity on the part of the Flint community to do something about the problem. “It is the children of Flint that really got the hard end,” McDaniel’s said, alluding to the fact that thousands of children – some estimates from leading pediatrician and researcher Dr. Mona Hannah-Attish point figures north of 14,000 – still suffer from lead poisoning that affects cognitive abilities.

Using the toxic Flint River as a water source to save money resulted in water moving through old pipes, loosening lead fragments and causing deadly leaching into the water supply. The New York Times reported that “30,000 school children (were) exposed to (the) neurotoxin known to have detrimental effects on children’s developing brains and nervous systems.”

The Flint Water Crisis sits at the intersection of so many different discussions, among them the deterioration of America’s inner-city infrastructure caused by corporations taking jobs out of the country to exploit cheaper labor in other poor countries, the reactionary nature of Black communities in relation to systemic issues like environmental racism; as well as the ability of Black communities to respond to crises with a grassroots self-determined attitude.

It is imperative that we see Flint not as an isolated incident but within the context of the wider system of environmental racism and the rapacious tendencies of capitalist exploitation as deep discussions of the necessity of self-determination amidst Black people/communities continue.