Katie Sobko

NorthJersey.com

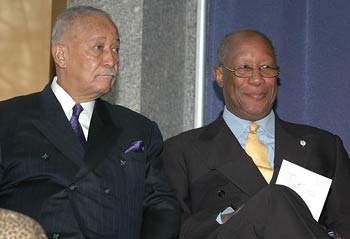

Peggy King Jorde has been involved in memorializing and preserving African burial grounds for nearly 30 years. What started as a project during her time working in the office of New York City Mayor David Dinkins has grown into a passion driving her to international activism.

with Mayor Dinkins.

Originally from Albany, Georgia, Jorde grew up in the segregated south, the daughter of an acclaimed civil rights attorney who counted Martin Luther King Jr. among his clients. She made her way to New York to study architecture and “never dreamed my journey would lead me here.”

“Here” is her home in Englewood, where she gave a virtual presentation recently on behalf of the United Nations about the value of preserving slave-linked burial places worldwide.

“Back in 1991 I was working for Mayor Dinkins, overseeing construction projects for cultural institutions, and when we found out the federal government was getting ready to build a new building, on the map we could see that the site was an African burial ground,” Jorde said in an interview. “From then on I just got involved in a lot of activism.”

I see New York as a gorgeous mosaic of race and religious faith, of national origin and sexual orientation, of individuals whose families arrived yesterday and generations ago, coming through Ellis Island or Kennedy Airport or on buses bound for the Port Authority,…”

Mayor David Dinkins in his inaugural address on January 1st, 1990.

The 34-story federal office building project triggered a cultural survey of the area mandated in the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act. During the survey, researchers uncovered a 6-acre burial ground “containing upwards of 15,000 intact skeletal remains of enslaved and free Africans who lived and worked in colonial New York,” according to a National Park Service website about the site, which is now a National Monument.