Black History

Black History Month: Dashikis and Dreadlocks

Learning to be Black and Proud

By Aishamanne Williams

I’ve had dreadlocks since I was 5 years old. My mother and father have them, so they were normal for me. I loved when my mother twisted my locks and put them in a ponytail or braided them.

image by YC-Art Dept

But my grandmother didn’t think they were normal. There were times when I’d be at her house playing by myself but listening to conversations between her and my mother: “If you’re not going to perm her hair, at least put some barrettes or bows in it. She needs to look more girly.” My mother’s responses were firm: “She doesn’t need to look ‘girly’, she’s already a girl. Her hair doesn’t need to be straight because she’s not white. She doesn’t have a problem with it, and it’s only when people begin telling her the things like you’re saying that she’ll start to feel like something is wrong with her.”

When my mother was a child, my grandmother combed and braided her hair. When she was a young adult she relaxed it herself. But when she got older, she became a Rastafarian, which is a spiritual movement centered around Black empowerment, living a natural lifestyle and praising Jah (God). That’s when she started wearing dreads.

My grandmother was worried that kids would make fun of me. I didn’t fear that because I didn’t understand it; I had no idea that my hair was something to make fun of.

I usually had it covered under a tam (my school allowed me to wear a hat to observe my religion), but when it wasn’t, classmates just asked innocent, curious questions like, “How long have you had locks?” Or, “Do they feel heavy?”

But in 3rd grade, when my parents switched me from private school to public school, that changed.

Different and Self-Conscious

At my new school, the questions about my hair were judgmental and mean-spirited. The school was predominantly Black, just like my previous school, but the students looked at me like I was different. The girls either permed their hair so it was straight or wore it in weaves. They wanted to know if I ever wanted to cut my dreads, if I felt bad about not being able to pass a comb smoothly through my hair. Even teachers asked me why my parents made me wear locks, as if they had forced me to do something against my will. There was an assumption that I didn’t like my hair. They felt sorry for me.

Whenever my friends had conversations about their hair, which was a lot, I didn’t join in because I tried to avoid the subject of my own hair as much as I could. But eventually, they’d focus on me; they acted as if my hair was something that happened to me, a punishment I was given.

“Would your parents ever let you cut your hair?”

“Yes, but I don’t want to.”

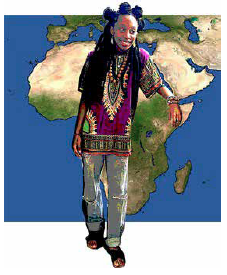

image by YC-Art Dept.

“Why not? Don’t you want your hair to be straight?”

“No, I don’t care.”

“I would die if I had to have the same hairstyle for the rest of my life.”

“I can put my hair into a lot of different styles.”

“So why don’t you do all those styles?”

“I don’t need to. I like it how it is.”

“Whatever. I feel bad for you.”

“For the first time, I became self-conscious. I worried that people insulted me behind my back. I tried to remind myself that my hair was a statement of pride, and my mother reinforced this whenever I spoke to her about it.”

“They don’t know themselves,” she would say, “and you do. They’re trying to be something they’re not and meet certain beauty standards, but you’re not doing that because you know yourself. Don’t ever let them make you forget who you are.”

She told me that society will try to make me hate my looks and aspire to be like the girls in the media, most of whom are white. Later, I learned that what my mother was talking about is “Eurocentrism”, a focus on European culture or history to the exclusion of a wider view of the world. “Your hair represents strength, spirituality and your African roots,” she’d say.

Black Girl Magic

When I entered 10th grade last year, a lot changed, both inside and outside. Phrases like “Black Girl Magic” and “Black Excellence” gained popularity on the Internet. New groups and magazines were dedicated to promoting self-love among people of color. Suddenly, it seemed like being Black was something to celebrate. Black performers like Amandla Stenberg and Willow Smith were outspoken about learning to love themselves and embracing their culture for its beauty. Learning about what it means to be Black and discussing it with other people helped me feel less different.

When I entered 10th grade last year, a lot changed, both inside and outside. Phrases like “Black Girl Magic” and “Black Excellence” gained popularity on the Internet. New groups and magazines were dedicated to promoting self-love among people of color. Suddenly, it seemed like being Black was something to celebrate. Black performers like Amandla Stenberg and Willow Smith were outspoken about learning to love themselves and embracing their culture for its beauty. Learning about what it means to be Black and discussing it with other people helped me feel less different.

On platforms like Tumblr and Instagram, I learned the term “cultural assimilation”. The idea that people of color have internalized Eurocentric beauty standards and have thus turned to self-hate began to make sense.

Even from a young age, these standards are embedded into our psyches as children of color; we subconsciously believe that anything related to whiteness is beautiful, and the farther you are from that standard, the less appealing you are. Now I understand why the girls in my school had such a hard time seeing my hair as “beautiful”: my hair is a radical expression of my blackness, and other people simply couldn’t handle it.

Beautiful Black People

The summer before 10th grade I’d discovered street festivals and fairs where African jewelry, clothing and other items are sold. Whenever I went to one, I saw beautiful Black people. They all looked different but had one thing in common: They were unapologetically Black.

Their freedom to express themselves was like an energy that radiated from them; you could see it in their eyes and feel it when they walked. They may have felt it in me, too because at every fair I went to at least 10 people told me how beautiful my hair was. I didn’t look any different at these fairs than I did at school, but the audience was different: I was surrounded by people who were trying to reconnect to their roots and embrace their blackness, so they saw the beauty in me. My friends at school were blinded by Eurocentrism. It wasn’t their fault.

Fortunately, my mother helped me to understand that. She’d taught me about the social, political and economic implications of my race, and I knew that most of my friends weren’t raised this way. Her words took on deeper meaning as I got older.

I started to express my newfound self-love at school. I wore African head-ties, clothing and jewelry. My friends complimented me a lot and it helped me make new friends with people in my school who saw that I was celebrating my culture and they admired me for it.

I Love Your Dashiki!

Every May, my school has a day called “Spring Fling”, where every grade is assigned a color and we come to school dressed in our respective colors. My grade had green, so I wore a purple and green dashiki (a loose, brightly colored shirt from West Africa), and an African beaded necklace with colorful earrings to match. I styled my hair up into buns. As soon as I got to school, the attention was all positive: “I love this look”, “Where did you get that dashiki?” “Your hair is so gorgeous”. The comments that really stuck with me were more specific, like, “I love how proud you are of your culture. It’s so admirable”. Or, “You’re so pro-Black. That’s really cool”.

The comments made me feel like loving myself was also about being an example to show others what freedom looks like. Two other girls in my grade started wearing dashikis. We are the minority, but we are being ourselves, causing ripples in the vast ocean of cultural assimilation and self-hatred.

Of course, you can be proud of being Black without wearing African clothing or dreadlocks. But by wearing these things, I feel I’m fighting the racist conditioning we’ve been subject to for generations. Seeing girls like me who celebrate their roots helps other girls feel more confident in expressing themselves however they want to, and that is important to me.