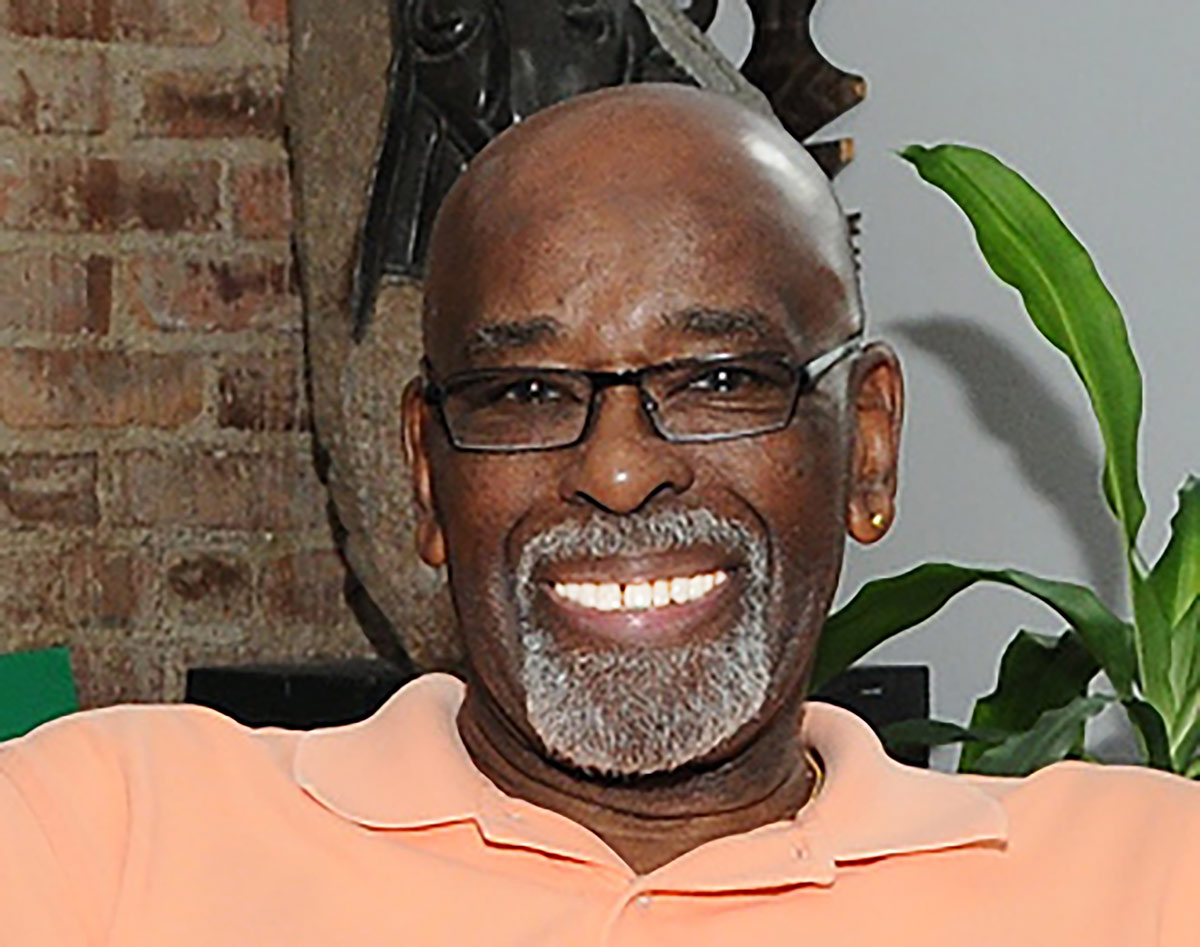

Roots, Branches of His Legacy Still Thrive

Q&A … with Al Vann, conducted October 2010

OTP: A lot of people run for office and there will be a lot of them running for your office. What were the kinds of preparations you had – and what had you done – prior to being elected that prepared you for leadership?

Councilman Albert Vann: Actually, I’ve thought about my life as a kid growing up in Bed-Stuy where I was born and bred. I went to PS 83 and JHS 35 before I went to Franklin K. Lane H.S. I didn’t realize the importance of it at the time, but when I was in public school I was always involved: on the stage doing stuff, head of the guard patrol in the school, president of the GO. I was very, very active in the school and the community and it wasn’t anything I thought special, it was just what I was doing, where I was.

After I graduated from college, my first real job was teaching. I taught at PS 256 then JHS 35 where I spent most of my years before the infamous 271 when I was principal over there, the year they were having the big problem with the teachers union in Ocean Hill-Brownsville. I was involved in organizing teachers into the Negro Teacher Association in 1964.

So it’s not really being a teacher I think that led me to this but the organizing of teachers and, actually, parents; holding workshops for them on the weekends, letting them know ,”This school belongs to you. Your children are there. You have the right to come in and make decisions.” And so forth. A lot of people probably can’t appreciate that time because they think the way things are now is the way they were back then. They were not. Parents were afraid to come to the school. They felt they had no say.

Obviously, it was a time when there was no Black curriculum and very few Black people involved. The point I’m making is that I was organizing, doing things that led me to politics; I didn’t plan a career in being elected to office at all.

Obviously, I didn’t know a lot about politics except my mother always said that I should vote and I would vote. I would look for names that looked Black and that’s who I would vote for because I really wasn’t involved in it.

But in 1972, it was more like a movement than a campaign because in ’72 we were still part of the movement. I ran against Cal Williams because people said, “We understand what you’re trying to do, Vann: trying to make decisions, trying to improve the community, you could probably do it better if you’re in elected office. You have access to the media, you have access to resources.” I listened and decided that okay, I would do that. So in ’72, we did not run in the primary. We ran in the general election and again my movement was teachers and the community.

We were the Vanguard Independent Party and we had petitioned just like the Freedom Party, today. It was a grassroots movement and we did well. Didn’t win, but we got a couple of thousand votes. People who were knowledgeable about the subject said, “Man, you’ve got to run in the primary. If you got 2,000 votes in the general election, you can win the primary.”

The second time around in ’74, I ran in the Democratic Primary and I won. That was the beginning of my career in elected office. We learned everything on our own. There was no one that mentored us. No one told us what to do; we had to learn by doing. So my people learned all the aspects of running a campaign, and I guess the rest is history.

OTP: So many folks want to run and I don’t get the impression that a lot of them are prepared as far as doing the on-the-ground community work. How involved was the African-American Teachers Association in the community?

Vann: Well, ATA (African-American Teachers Association), which really began in 1964, as the Negro Teachers Association, actually started with the teachers at PS 35 and PS 21 and then expanded. Eventually, we had a chapter in each borough except Staten Island. We had a coordinator of African-American teachers in each borough except for Manhattan, then we became citywide and the primary force dealing with the UFT (United Federation of Teachers). It was the ATA members who transferred into Ocean Hill-Brownsville, when that struggle occurred in 1968. So we took on the UFT and fought a lot of battles and had a strong voice. I was also involved with Youth-In-Action. I was on the first board of Bed-Stuy Restoration.

OTP: This was based on your teaching and work?

Vann: It was based on being involved in the African-American Teachers Association. Teaching was a base, I guess, and then organizing teachers and parents was an aspect of the teaching and went beyond the classroom and school and into the community. Parents had to be orientated and told what was going on and so that put me out there in the community, but I still wasn’t thinking politics or making it in elected office, at the time..

Others said, “Maybe you would want to consider that.” So it was involvement in the community that evolved to a point, as opposed to people saying, now: they want to be in office for whatever reason; some good and some may not be. Then, they do what they got to do: put up some flyers, raise some money to put themselves out there. And then people have to decide if they’re worthy or not.

I don’t expect everybody’s preparation to be like mine. But I think that the community has to look for people who have the community feeling. If you’re not trying to do something for the community before you get elected, you mean you’re going to start trying after you get elected? There’s no history there.

OTP: How has the community changed throughout the years since you first came into office as an elected official?

Vann: We had gone through the Black Power Movement in the sense of Black consciousness; we were identifying ourselves as African-Americans; Buy Black was occurring and the next stage was the quest for political power. We didn’t have a lot of Black elected officials and then the coalition for community empowerment formed: Roger Green, Clarence Norman, Thomas Boyland, Velmanette Montgomery, and so it goes on and on from there. It was an explosion and it was a continuation of a movement, not just running campaigns. That was the generation we were a part of and because of that, I was positioned. In the Assembly, I chaired the Black and Puerto Rican Caucus, where we had an opportunity to sue the city and the state and to create a lot more power seats for our people. With two Congressional districts, we increased the number of city council districts. This is power.

We created political districts for our people that were not there before. So all those seats of power came about from the movements that I and others led. And it was not just me: Major Owens obviously played a key role and we moved from there. So that’s what happened.

Now, where are we today? Probably a lot is taken for granted and obviously there is not that same sense of urgency now; people are used to having Black elected officials. I’m not sure we were as critical of our own elected officials as we should be. We tend not to have – even in my younger days the Black community – never had a way of judging and/or keeping the elected officials accountable.

In our community there was no local paper, other than the Amsterdam News, to keep us abreast of the votes on the issues and so forth.

I think [we] the community is responsible in the sense of not holding us accountable by knowing what it is that we politicians are supposed to be doing, and making sure it’s done.

But then again this means that unless the elected official is self-motivated and strongly committed, then … there’s not necessarily a lot of room for independent thinking or independent action. Therefore, you have to know who you are; and be very strong. I found that the “powers-that-be” respect integrity. They may not have it, but they respect it and they respect independence.

So if you’re coming from the community and your community is, indeed, your priority, then you’ll do OK – you’ll do fine. It’s when you try to be like the others that problems begin. You can’t have two masters. You can’t have the community as your master and the leadership of any House as your master.

You deal with that by being as supportive as you can, and there are issues, values and principles that you cannot give to anyone and I think that makes a difference.