Black History

Interview RICHARD GREEN CO-FOUNDER, CROWN HEIGHTS YOUTH COLLECTIVE PATRIARCH, AMERICAN HERO

Richard Green: When the cuts came down in December before Christmas, Boom! They just cut. Not only did they cut the budget, they froze everything. If you didn’t have a reserve in your cash flow when this happened… most programs had to close. I said, “I’m not going nowhere. I’m digging in for the long haul!”

David Greaves: How did you weather it?

RG: I took a mortgage out on my house.

DG: For the Center?

RG: That’s how we kept operating. I took out a second mortgage.

________________________________

Published April 1996

By David Mark Greaves

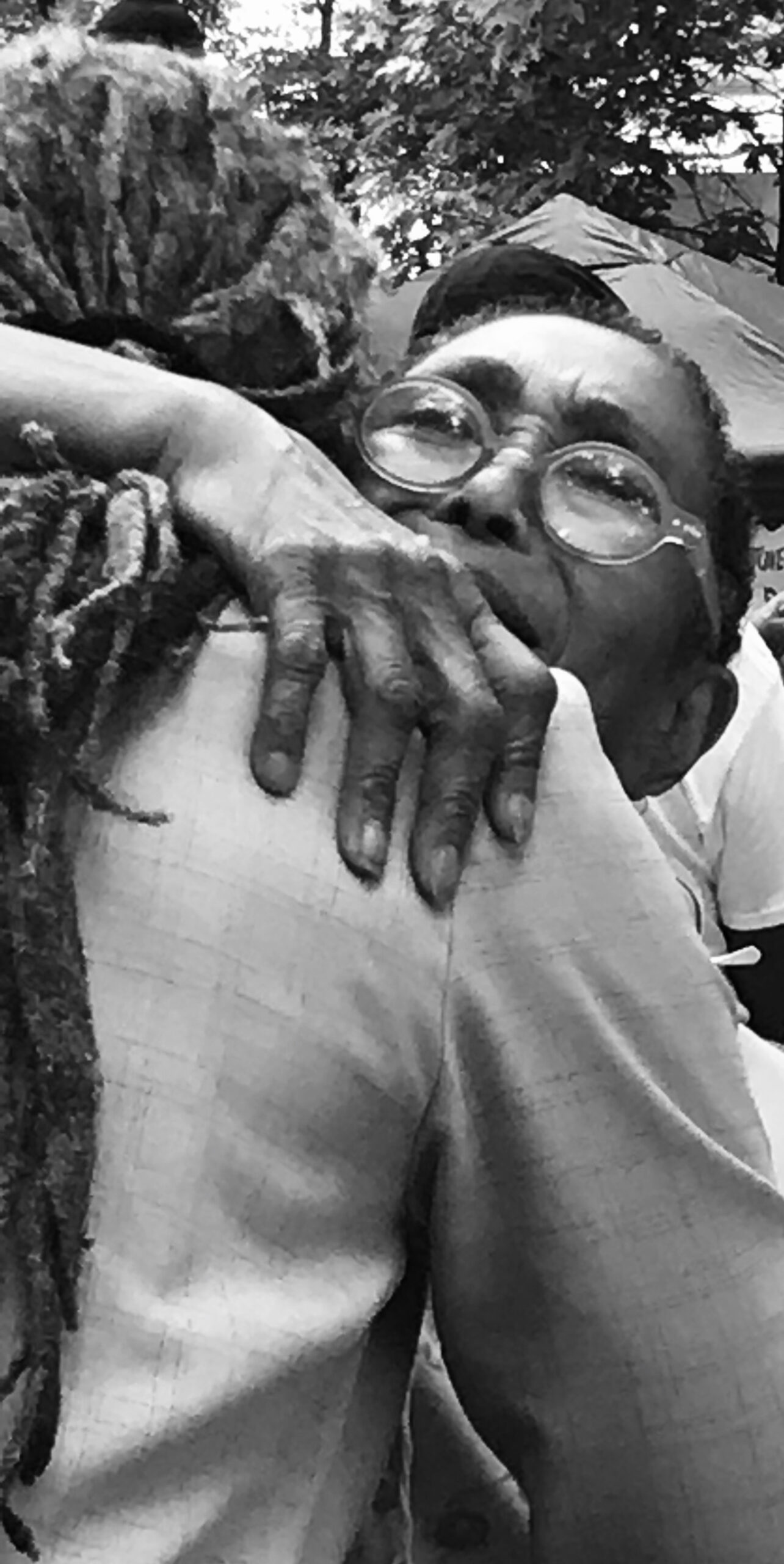

Recently, many African Americans have been talking about “giving back” and “helping the youth.” Richard Green is glad to hear it, he can use the help. Green has made “giving back” a part of his professional and personal life since his return from Vietnam in the 60’s. He has taken as many as 65 youth ranging in age from 2-22 years to such countries as Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, Gambia and Mali. Next year, the Collective travels to Egypt and Ethiopia. He has brought four basketball teams from Nigeria to play throughout the U.S. He has organized annual food and clothing drives to Africa and has been a year-round life preserver for young people as they make their way through Brooklyn’s troubled seas. Usually associated with teenagers and “Keeping the Peace,” he seemed to be everywhere during the crisis in Crown Heights a few years ago. The Crown Heights Youth Collective, Inc was founded in 1977 by Richard and his wife Myrah, now parents of five and grandparents of one. A visit to the facility, now located at 915 Franklin Avenue in Brooklyn, reveals him to be deeply active in the lives of young people in a number of ways. The center is housed in a cavernous industrial building that is made exciting by the activities going on all around. There are classrooms, games, carpentry shops and areas to sit, talk and create. A computer lab is there and an in-house retail store, run by the youth, is being built. When he’s not involved in street outreach or working in the center open area, Green can be found in an office lined with awards, children’s artwork, and papers and files in piles on every available surface. A tall man with dreds, he is a calm and charismatic presence. As I sat and talked with Richard Green about his work, I began to realize that heroism takes many forms and that here in Brooklyn, we have a real American Hero.

David Greaves: How long have you been here doing this? We always talk about folks having to participate, and here you are.

Richard Green: We started 20 years ago. 1997 will make 20 years. I just thought there was just so much of a need in the community I grew up in and raised myself in to have something that young people could relate to. I (felt) I had an obligation to come back to this community. I grew up here, came out of the service, went to college; everything happened from here. So, I just came back home. Many of my brothers were getting that degree in the early-late 60’s and early 70’s. Many went to school on open admissions. And they took the flight … to Long Island, upstate, different places. I grew up in the same zip code that I’m living in right now and working. I used to walk by the house I’m living in now when the neighborhood was called “Doctors’ Row.”

DG: I grew up on St. Marks and Kingston.

RG: So, you know this area here. I used to walk down this block and look at the houses and say, “Boy, it’d be nice to live in one of those.” I finished school, finished my graduate work, came back home. I looked out the window one day and saw the little brothers on a rooftop when they were supposed to be in school. I yelled out my window, “Why you all not in (school)?” (They said) “Well, you know, it’s boring in school.” “So, what do you do when you’re not in school?” “There’s nothing for us to do.” I’d just moved back in the neighborhood. So, I went around and saw there was a community center around the corner on Bedford Avenue. I went inside, introduced myself and asked the brother if there was any way I could work with him. I was just coming back at that time and I wasn’t doing this kind of thing. I’d done it briefly out in Flatbush the summer before. So, he said, “Yeah, come on and work with me.” So, I started here. Things happened and that program closed. I moved off, went somewhere else in the neighborhood. Stayed right in the vicinity and ended up opening up my own place, started a program between the room around the corner that I had to tutor in and my apartment. We did our T-shirts and stuff in my bedroom on my bed.

DG: For fundraising?

RG: Fundraising and shirts for our teams in sports. T-shirts were always a good incentive for young people. So, we started that way and before you knew it … Well, the need is there.

DG: Did you find that more and more kids just started to come?

RG: Just kept coming. They used to say, “When the students are ready, the teacher will appear.” Well, when the teacher is ready, the students will appear. You appear out here to teach these young people anything and they’ll be ready. And that’s what we started doing. We became the teachers.

DG: You say, “We.” You and …?

RG: I met a sister who was working at Lord and Taylor and I convinced her that this job…we weren’t on payroll or anything — was volunteer. We were struggling, starving, collecting unemployment, whatever, to keep going. I convinced her to come out here and work with me.

DG: A fellow believer?

RG: Ended up marrying her. And she was my partner, someone I could bounce things off of. (We) have that yin and yang thing going. I have that yang side to make me balanced. We managed to raise a family as well as to continue with this.

DG: How has that worked out over the years?

RG: We’ve been through many changes, different plateaus. We had a serious fire that took us out five years ago.

DG: Here?

RG: Not in this site but in the other site. When that happened, we thought that was it. But one thing after another, we sprung right back and five years ago, we opened this site.

DG: I haven’t had a chance to walk around yet, but just glancing inside, it’s very impressive. How many kids do you work with in the course of a year?

RG: Thousands. I work in schools, go to prisons, whatever it calls for, we’re here. We literally deal with thousands of young people in a given year. Today is a good day for you to see. Today is a Tuesday. How many young people have been in here already? The first crew that was here …well, you’re talking 70 young people who go to school here. When they go home, we have after-school programs for 40 additional new youth. Then you have the evening people. With the quiet games, meetings in the library, you have an additional 30 young people. There’s karate…so count that up and you see what’s done in a given day. If I go out here and do outreach after school, that’s another group of young people.

DG: Do you actually go around to schools and stand out front?

RG: Yes. That’s the science that’s holding this whole thing together. The Police Department and others talk about the reduction in crime, when under Mayor Dinkins’ Administration, we wrote a project, the most important project that came to this city. We started with six neighborhoods and now we’re up to fifty-something with our street outreach vans. Street outreach was the most important thing we brought into existence. It gave the opportunity for us to intercept these young people before it got to the critical point. That program’s been all but pretty much decimated. Right now, we’re praying that the mayor, the administration, will keep it going. But like anything else that’s good, once it’s good, it has pretty much out served its purpose.

DG: I’d like to ask you about credits for drops in crime. I see the police commissioner polishing his brass and the mayor saying, “Yes, look at what we’re doing.”

RG: Yes.

DG: And I have a suspicion that there are community-based forces that deserve credit for reducing crime. How do you feel about it?

RG: In all the different statistics, crime is going down except among young people. It’s an overall go down. But young people are more reflective (these days). Whenever a young person commits a crime, usually a street crime, it’s considered newsworthy. Adults are the ones who make the choices as to what to report. A boy once asked his dad, “Why is it whenever a lion attacks a hero in the movies, the lion always loses?” So, his dad says, “Son, as long as the lions are not writing the story, they’ll always lose.” It’s the same with young people. Our young people don’t write the stories so what gets projected is distorted. Adults commit as many crimes in various areas, and in many cases the youngsters are emulating the adults, acting out the adult crime, but they don’t get reported.

(There’s a knock on the door and a woman is invited in.)

RG: Hi. You can look around.

NYT: Do you mind if I stay?

RG: Do you mind? (To Greaves)

DG: No, I don’t.

RG: She’s one of your competitors. The New York Times.

DG: This is Mr. Greaves. Here, let me show you a copy of his publication, OUR TIME PRESS.

NYT: Oh great. Thank you.

RG: A Brooklyn-based publication.

DG: Here are copies of the first two editions.

NYT: Thanks.

DG: (To Green) You hear that 75% of the folks incarcerated come from seven neighborhoods in New York. Is this one of those areas? What are the statistics?

RG: Yes, Central Brooklyn, Crown Heights, Bed-Stuy, Brownsville, those are a part of that statistic. Brownsville, Harlem. When you make an analysis of it, it’s like it’s set up intentionally to create the atmosphere for these young people. Okay, granted. The Police Department has had a lot to do with the reduction of crime, but you have to take in all the different pieces of the equation. What has happened, what has been done differently, we’ve created a new culture in this community. You have a culture of sanity and peace among these young people, and we maintain that at all times. We don’t bind to that notion of chaos that they’ve been accustomed to. When you come in here you come into a level of sanity and peace. You walk in this neighborhood, the same thing. We’ve just done a big extensive piece on graffiti. Graffiti is violence, so what we’ve done is we’ve taken the violence away from the walls and put it in other places. We have them coming in now and showing us their books of “tags.” (These books) are loose-leaf binders or art books. Just like when you had your autograph book in high school. Each one will tag the other one’s book for them. So, we’re getting them into a new science of tagging. We’re talking about putting tagging on the Internet. If you want to get on the Internet why not put your tags on it. Every young person tags because they want to get what they call “ups.” Ups is like rank. I can read most of the tags, I know most of the tags on the street and I know how many people have different ups. And if you have a lot of ups, that gives you the “props” in the neighborhood. So, they go out there trying to get as many ups as possible. They want to get “motions,” they want to get “burners.” The ones with a lot of colors are called burners. Now, when you get a burner up there, you’re really good because you’re writing with like three cans at one time and spraying…

DG: Okay. So, instead of putting their tags on the walls, they’re putting them into the books …

RG: And blending. You know like artists do with a palette. They’re doing it with cans now. It’s a science. The book will be out in a little while, God-willing. It will be out at the end of the month. We did the first book on a compilation of tags. We have over two thousand five hundred tags from not only Brooklyn but as far out as Chicago, Boston, Atlanta, Virginia. All over the country there’s tagging. We put it in a book. So, when we give them that book now, they’re going to understand two things. On every other page in that book there’s information they’re not going to get in school: where it all started, going back to ancient Egypt and the whole science of tagging.

DG: Do they have writing projects also?

RG: Everything is in the book. It’s 230 pages. It’s a compilation. There are writers in there, I’ve had young people write about what does culture mean, what does art mean, small one-page blurbs. It’s all in there. That’s Book One. It could be a hundred volumes because now they’re going to take it over. Take it off the wall. Quite aggravating to me and you. When you walk out there and see your wall or your car or truck tagged, it’s aggravating.

DG: So now they’re going to tag in the book and distribute it that way?

RG: They want to have ups. We’ll show them how to get ups. The best taggers in the neighborhood don’t have 2,500 ups. So, we’re showing them how they can rechannel their energy and get the recognition they’re looking for. During that trouble we had in Crown Heights, we worked hard to keep the lid on. We saved not just the city and the state, but the country as well. New York is the leader. When we go, every place else goes. People must understand that. (To be continued)