Interview

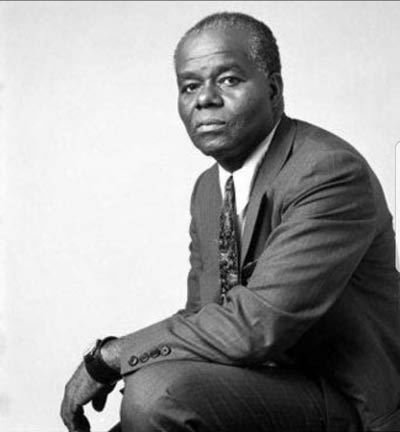

In OUR TIME…Dr. John Henrik Clarke

The following is a reprint of a 2002 reprint of a 1996 interview with legendary historian and great teacher, Dr. John Henrik Clarke.

A recent report in the New York Times demonstrates how Republicans are redistricting African Americans out of political power wherever they can, and White supremacists are working on taking over the federal government, we thought this interview is still useful going into the new year.

Dr. John Henrik Clarke was born in Union Springs, Alabama and grew up in Columbus, Georgia. A professor emeritus in New York City, Dr. Clarke was recognized worldwide as a leading Pan-Africanist and authority on African and African-American history. Our Time Press interviewed him October 23, 1996, and as we ring in the New Year, we thought we’d once again share his thoughts, still meaningful and centering for a people.

Our Time Press: Where are we now? Where are we going?

John Henrik Clarke: We are a loose nation searching for a nationality. The population of African people in the United States is far in excess of six small European nations. Where we are going? We have to go back as best we can to where slavery and colonialism took us from. And they took us from a concept of nation management and nation maintenance. We have been so long away from home that we, unfortunately, have forgotten how we ruled states before the foreigners got there. We did very well. We produced a state that had no worth for jails because no one had gone to one; no worth for prostitution ‘cause no one had ever been one We did not produce a state with a whole lot of nonsense about rugged individualism, but we produced a collective state. You had to function in relationship with the total state. You didn’t do your thing unless it was in keeping with the maintenance of the whole people. It wasn’t a personal ego-personality type of thing that we have now. “I’ve got my rights. Mind your own business.”

In a collective society, everybody’s business is everybody’s business. Your behavior determines, to some extent, the destiny of your nation and your group. Therefore, your group has a right and responsibility to preside over your behavior and you have a responsibility to make that behavior in a manner that does not endanger the group. This kind of collective society — giving to each according to his need — existed in Africa not only before Karl Marx, but also before Europe.

In the African matrilineal society, the lineage of the bloodline comes down through the female side. The Arabs who invaded East Africa and other parts of Africa reversed it to the patrilineal, where everything comes down through the male side and the woman has no basic rights except that which the male is willing to grant her. In a matrilineal society, a woman has basic rights that no one has to grant her, but you can’t take it away from her because the society is based on the concept that the life-giver is equal to those she gave the life to.

You can see in our churches most of the males are pastors. Most of the deacons are males. But if the woman withdrew her support from our churches, you’d have to close the doors. Yet, she doesn’t shout about (what she does). She doesn’t rant about it. She just goes ahead and does it. This is where our movement differs appreciably from the white woman’s lib. The white woman has never had the co-equal status that the African woman has had.

OTP: What’s been the effect of racism? How has it changed the mental structure of Black people?

JHC: It has changed the mental structure of the whole world because it presupposes that God, in his lack of mercy, has made one people better than the other. To make one people better than the other would be ungodly in the first place. If God is love, then God has no stepchildren to love. The impact of racism has changed our look at ourselves because basically racism was meant to make us look unfaithfully at ourselves, and to not treasure our institutions. People rise and fall on the basis of the makings of institutions.

OTP: You speak to groups. You speak to individuals who have a level of consciousness that brings them to your lectures. But there are those — when you leave your house in Harlem — who you pass who just don’t have a racial consciousness that moves them towards empowerment of themselves and their people.

JHC: That’s because they have been programmed in thinking that hope is integrated into something belonging to someone else other than something that is distinctly their own.

Now, Jews integrate but they don’t destroy their institutions. They don’t close the synagogue. They don’t stop having special Jewish graveyards. They don’t stop having special Jewish holidays. Why can’t we understand that we can have things special to us and still comingle and integrate with others. But the one thing you never integrate at the ruin of your own pleasure is your institutions. This is what’s bothering me right now. The southern white Baptists now want to integrate with the Black Baptist church. I say that would be the end of it. In the first place, most white Southern Baptists can’t preach, their intentions are not that good and we make a different joyful noise unto the Lord than white people. When we say, “Lord Jesus, personal savior,” we may not mean the same thing as what they mean.

…If people do not know where they have been and what they have been they don’t know what they are. They don’t know where they are going to have to go or where they still have to be. History is like a clock, it tells you your time of day. You look at a clock and it tells you it’s eight o’clock, you know the number of hours that have been before eight, you know the number of hours you’ve got after eight. You can now measure your time to see if you can get done a number of things you’ve got to get done. History serves the same purpose. It’s a compass that you locate yourself on the map of human geography, politically, culturally, financially.

OTP: This is the closing out of 1996. In three years, there is the Millennium. What about Black folks?

JHC: I say if Black people don’t unite and begin to support themselves, their communities and their families, they might as well begin to go out of business as a people. Nobody’s going to have any mercy. And nobody’s going to have any compunction about making slaves out of them. No more religion anymore. No more of who’s a Muslim and who’s a Protestant. I have no faith in much-organized religion because I think it’s by a bunch of hypocrites and practiced by a bunch of hypocrites. They don’t mean what they say because all of them are in the slave trade one way or the other.

OTP: What about the whole issue of violence as it relates to our people in this society?

JHC: Violence among all people is based on dissatisfaction, frustration and crushed ambition and people who don’t know who to strike at and who to blame are not willing to blame themselves.

OTP: How do we counteract it all?

JHC: We counteract it by getting closer to our children. By talking to them. Someone asked me the same question one time when I was out lecturing and I gave them a true answer I still believe in. Break all the TVs, burn all the Bibles. Maybe you’ll get their attention. …Educating a child won’t be difficult if you get through to the parent. You have to convince the adults that if a child is to learn his culture, he or she will have to see his mother and father reading about it and explaining it to him. Then it gets a legitimacy it otherwise would never have. Until then, his learning is limited.

I came from a very poor background, a very loving home. My mother died when I was 7 or 8. My father was a sharecropper and he moved from Alabama to Columbus, Ga., hoping to make enough money to go back and buy land. My mother really held the family together. She was a perfect example of the kind of Black woman I would love to see again. She ruled my father with an iron hand, yet she barely ever raised her voice above a whisper. She would say, “John, I suggest…”. She would congratulate him for having the wisdom of such an idea as though it was his in the first place. She never impinged on his manhood. The worst thing I would hear was “Behave yourself. Wait ‘til your father gets home.” I could pull all kinds of games on her. I couldn’t pull any games on my father.

I attended a Baptist church as a child and was an avid reader starting with the Bible. I taught the Junior Bible Class and Sunday School in Columbus, Georgia at age 10. The churches I attended included Friendship Baptist, Gethsemane Baptist and Macedonia Baptist in Columbus. Here in New York, I attended Abyssinian to help out with the plays and the activities there. I don’t attend any particular church now. I don’t believe in denominations, nor do I believe in organized religion. But I was always active. Attending church is one thing, belonging is another. I believe in spirituality which is out there. I believe in doing good for goodness’ sake. Service is the highest form of prayer, as far as I am concerned.