Black History

EBONICS: Its Origins and Significance

In 1996, the Oakland School Board started a furor by recognizing Ebonics as the primary language of African American children to assist in the teaching of standard English. Psychologist Dr. Robert Williams, writing in his 1975 book, Ebonics: The True Language of Black Folks, defined it this way: “the linguistic and paralinguistic features which on a concentric continuum represent the communicative competence of the West African, Caribbean, and United States slave descendant of African origin. It includes the various idioms, patois, argots, idiolects, and social dialects of black people,” especially those who have adapted to colonial circumstances. Ebonics derives its form from ebony (black) and phonics (sound, the study of sound) and refers to the study of the language of black people in all its cultural uniqueness.”

David Mark Greaves

Our Time Press 1997

As you study the question of Ebonics, you see why it is not a question for white people to answer. To look at it squarely means examining the history of slavery in America. For African Americans, it lets you see more clearly who you are and what you must do. For white Americans and their black spokespeople, it represents the danger of looking at the underbelly of White American wealth and privilege. It means putting Ebonics in context. And let’s do that now. First of all, Ebonics is the African-American’s linguistic memory of Africa. In the same way that you hear any accent, whether Chinese, Russian, Italian, or Hispanic, you are listening to our African accent when you hear things like “mo” instead of “more” or “ax” instead of “ask.” It’s an accent that many of us still hold on to, despite being able to speak English better than many of our employers.

We hold on to it in private moments with ourselves or our friends; there is no wrong with that. Let us take a moment and look at Ebonics in its context. As with other nationalities, when Africans were brought to this hemisphere, they came carrying their many languages and learning. But unlike any other nationality, everything else was taken from them, and they were delivered physically decimated and naked on these shores.

Those that survived the 240 years of the Middle Passage (1619-1859) found themselves now Africans in America and held captive by people who viewed them as property to be bought, sold, used, and raped. Forbidden their own languages, the Africans began to use local words to identify objects and their environment. They standardized on the local language, whether it was French, Portuguese, or English. For the Africans, this learning process had to be done in an atmosphere of terror, where killings and beatings were only an upward glance away. As the centuries passed, and American slavery centered more in the South, many Africans escaped into the North or joined others in the tribes of the Indigenous people. Communities were formed from the Seminoles of Florida to the Brooklyn, NY, districts of Weeksville and Vinegar Hill.

Those escapees to the north found each other through each other and worked together to build their communities. By the 1800s, the Africans had positioned themselves to build schools and large churches. They built the schools because they knew the importance of learning, and they built the churches because God was the only other being who would help them. In the pamphlet “Weeksville Then and Now,” authors Joan Maynard and Gwen Cottman show the importance of learning and self-help to Africans. They have a replica of “The Freedmen’s Torchlight,” a community newspaper published by the African Civilization Society housed in their building on the corner of Dean Street and Troy Avenue in Brooklyn, NY. Dated December 1866, a year after the Civil War ended, it included stirring statements of its philosophy of Black self-help, information on the Freedman’s Schools, and featured moral anecdotes and listings of their contributors.The front page was devoted to the Alphabet, basic English, Arithmetic, Geography, and views of the nature of God and Man. In this way, the newspaper also served as a textbook for the newly freed to learn reading and writing. Some organizations before and during the development of Weeksville were the New York Society for Mutual Relief, which held its first public meeting in 1808; the African Woolmen Society, founded in 1810; the Brooklyn African Tompkins Society, founded circa 1827 and the Weeksville Assistance Society, circa 1854. A chapter of the Prince Hall Free and Accepted Masons started in Brooklyn with the formation of Widows Sons Lodge, No—II, in 1849. And then there were the churches. “Brooklyn’s first Black church, the Bridge Street African Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal Church, was incorporated in 1818. This church had the reputation of being a terminal on the Underground Railroad. The Bridge Street Church was then in Brooklyn’s oldest Black settlement, located near downtown Brooklyn.”

“Education for Black children in Brooklyn grew from the independent efforts of Black religious leaders such as Peter Croger, who had a school in his home in 1815. In 1819, William M. Read, a New York African Free School graduate, was teaching Black children in segregated settings. However, by 1827, even these quarters were denied. By 1840 some Manhattan Black folks who had settled in Carsville, just south of Weeksville, had established another African school.”

While this was going on in Brooklyn, legal slavery was the reality for the vast majority of Africans in the United States. Because it was against the law to teach Africans to read and write (and the penalty for doing so could be death), this had to be done in secret places by an exhausted people who had been worked hard in the fields, from sun up to sun down. And it was by candlelight that the English language was learned. More generations of social isolation passed, and some Africans who remained captured in the South were being called upon to perform more complex tasks on the plantations and in the manufacturing areas. They were used as expert farmers, builders, and craftspeople. Brooklyn’s Professor William H. Mackey notes that enslaved people made the furnishings of Thomas Jefferson’s mansion, and they built the house itself. Many masters were breeding their personal slaves themselves. Fathering mulatto children who were raised with his white children and often educated with them. Frederick Douglass was such a man, and his command of the English language, in speech, and by pen, took him to world recognition as the publisher of “The North Star” newspaper and a leading abolitionist.

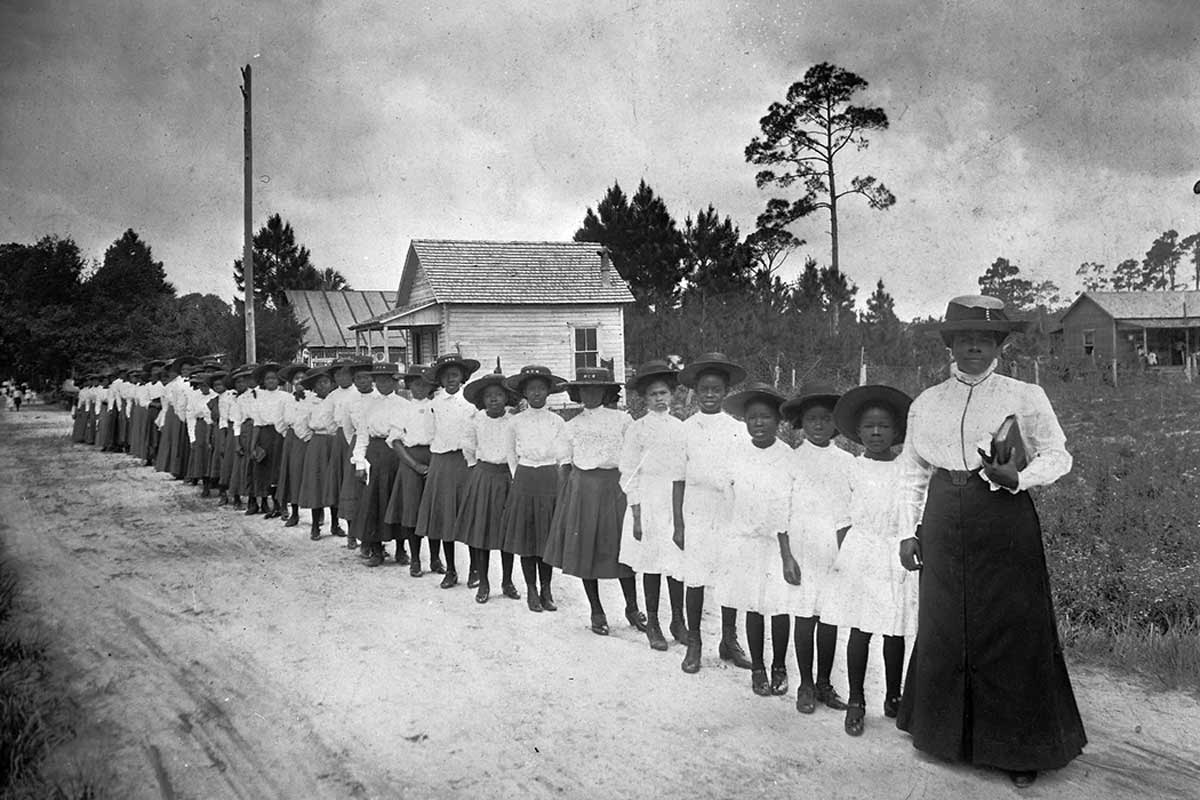

Africans knew the value of learning. So much so that teachers were heroes. People like Booker T. Washington, and Mary McCloud Bethune, were people celebrated for their ability to teach.

Our universe of heroes includes W.E.B. Dubois, Frederick Douglass, and Ida B. Welles, who dedicated their lives to the survival and illumination of their people.

The institutions were segregated, as were the institutions that taught the teachers. Because of this need, the Africans built their own teachers’ colleges. People like Dr. Benjamin Mayes of Morehouse and Dr. Booker T. Washington are teachers whose imprints are felt in society today. So Africans in America need to apologize to no one for wanting to take care of our own. The struggle has always been that and continues to this day.

Now is the time for activists and educators to reframe the answer to the question, “How do you best teach African-American students?”

A proper introduction model would have looked like this:

- A black think tank issues a report on African American comprehension of standard English as reported by national test scores.

- Teachers are studied to determine the characteristics of the best teachers.

- Determine that the superior teachers could communicate with their students.

- Devise a “special education” course for teachers called a career enhancement seminar. This would be understood both ways. For the community, a “Special Ed” course for teachers would be refreshing. A good dose of their own medicine. It would be a real career enhancement opportunity for the teachers because if they intend to continue, they had to study African-American history from the African American perspective as vigorously as they studied Western civilization. The teachers will be taught to understand the necessity and urgency of providing the African American youngster with the best language skills possible. Other tools include math skills, analytical thinking, and written and oral expression. The teachers’ career development would hinge on increasing student test scores in these areas on national tests.

During their training, they would study West African Language and trace the language patterns throughout history to their present-day classroom. Then the student’s use of language becomes immediately understandable and respected. Using that understanding, they are then able to teach more effectively.