National News

Dr. Robert Bullard: Houston’s “Unrestrained Capitalism” Made Harvey “Catastrophe Waiting to Happen”

“I’ve lost everything.” “I’ve lost everything I owned.” “Only the clothes on our backs.” These are the words of tens of thousands of Texans whose lives have been instantly changed forever by Hurricane Harvey, the storm the National Hurricane Center is now calling the biggest on record. Wet, hungry, tired and dependent on the army of officials and volunteers, life will now be marked and divided between pre- and post-Harvey. For now, they are in despair, facing rebuilding from scratch and standing as yet another warning of the future coming for millions more because as the seas get warmer, they evaporate faster, as the air gets warmer it holds more water and reports are that over 15 trillion gallons has already fallen on Texas and more will be coming in the years ahead.

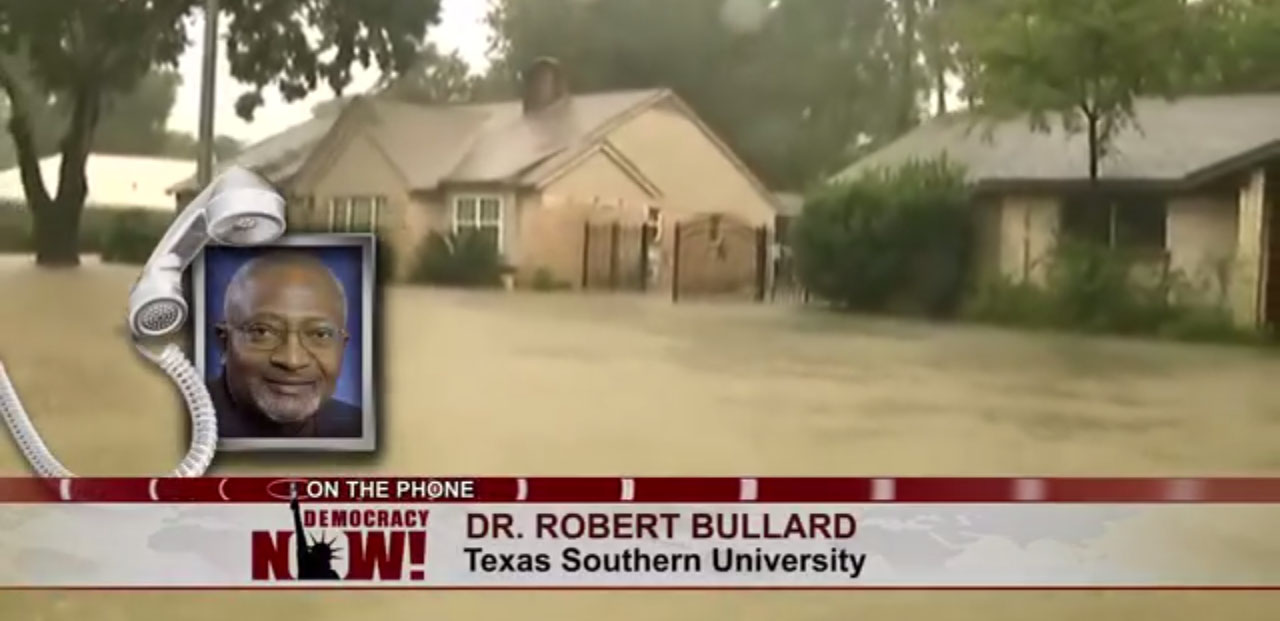

Disasters strike especially hard on the poor and those who historically have had less. Dr. Robert Bullard, known as the “father of environmental justice”, was interviewed on Democracy Now! by Amy Goodman and Juan Gonzalez. Dr. Bullard is a distinguished professor at Texas Southern University and former director of the Environmental Justice Resource Center at Clark Atlanta University. Dr. Bullard was interviewed by phone from his home in Houston, which he was to be evacuating right after he spoke as the floodwaters were still rising at the Brazos River. Below are excerpts from two interviews, seen in their entirety at: www.democracynow.org DG

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Bullard, thanks so much for being with us. Can you talk about the situation you are in and so many people in Houston are in right now? Describe the scene for us. And then, how you relate it to your life’s work, to the issue of climate change and environmental justice.

- ROBERT BULLARD:Harvey and the aftermath, the flooding of Houston and the surrounding areas, it’s of biblical proportions. This is a nightmare. And the images that you see on television and you hear the voices of people who have been just totally destroyed. And this is a situation where I think it’s telling us that we have to change.

We have to change the way we do business and the way that we as humans interact with our environment.

And this is basically the situation where this storm, this flooding of this city, tells us that there is no place that is immune from devastation. I worked in New Orleans in the flooding after Katrina. New Orleans was only 500,000 people. Houston is 2.3 million people. And then you look at the surrounding areas. You’re talking 5.5 or almost 6 million people. It is historical proportions.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And Dr. Bullard, to what degree do you think unchecked development by Houston’s officials over the past several decades has created an even worse possibility for calamity when a natural disaster like this hits?

- ROBERT BULLARD:Well, Houston is actually—was a catastrophe waiting to happen, given the fact you have unrestrained capitalism, no zoning, laissez-faire regulations when it comes to control of the very industries that have created lots of problems in terms of greenhouse gases and other industrial pollution. The impact that basically has been ignored for many years.

And so the fact that—it is a disaster, but it is a very predictable disaster.

And those communities that historically have borne the burden of environmental pollution and contamination from these many industries at the same time are the very communities that are bearing disproportionally the burden of this flooding. So you get this preexisting condition of inequality before the storm, and this inequality in terms of how people are able to address this disaster because of vulnerability. And I think what we have to do is look at lessons—well, not learn from Katrina in terms of the rebuilding, redevelopment and recovery.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: There has been quite a bit of second-guessing of Mayor Sylvester Turner’s decision not to call for an evacuation of the city. I am wondering what is your take on that, especially given what happened with Hurricane—was it Rita?—a couple of years ago when there was an evacuation effort made, but more people ended up dying—about 100 people—in the gridlock that occurred as people tried to leave a city as large as Houston.

- ROBERT BULLARD:Well, it is easy to second-guess, but the fact is that trying to evacuate 2.3 million people on these highways is almost a task that is impossible. And so I don’t think there was anything that you can say, “Well, why is it that the mayor and the county judge decided to go this way?” When you look at the problems of logistics and trying to move this many people on these highways getting out of the city, that probably was not a good choice to make.

So I think the decision to have people shelter in place—and no one could predict what happened afterwards. So I think the best that we can do now, instead of pointing fingers, is pointing to solutions and pointing to ways that we can address the many problems and challenges that we face today. And having to evacuate and leave your home and go out there and not know what is ahead of you. You have your life, and I am blessed that—when you see those images, you can see that this is pain.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Bullard, I want to talk about this issue of justice. You live in the fourth-largest city in the country, Houston. The most diverse city in the country, Houston. And it is the “petro-metro”. That’s right, the Houston area is home to more than a dozen oil refineries. The group Air Alliance Houston of warning the shutdown of the petrochemical plants will send more than a million pounds of harmful pollution into the air. Residents of Houston’s industrial communities already reporting unbearable chemical-like smells coming from the many plants nearby.

Yesterday, we interviewed Bryan Parras with the group t.e.j.a.s., the environmental justice group, who said, “Fenceline communities can’t leave or evacuate, so they are literally getting gassed by these chemicals”.

Can you talk about the significance of where people live and the disproportionate impact of climate change on communities of color and poorer communities?

- ROBERTBULLARD: Well, the best predictor of health and well-being in our society, and including Houston, is ZIP Code. You tell me your ZIP Code, I can tell you how healthy you are. And one of the best predictors of environmental vulnerability is ZIP Code and race. And all communities are not created equal. Houston’s people of color communities historically have borne the burden for environmental pollution, and also the impact of flooding and other kinds of natural and man-made disasters.

When we talk about the impact of sea level rise and we talk about the impacts of climate change, you’re talking about a disproportionate impact on communities of color, on poor people, on people who don’t have health insurance, communities that don’t have access to food and grocery stores. So you talk about mapping vulnerability and mapping this disaster and the impact, not just the loss of housing and loss of jobs, but also the impact of having pollution and these spills, and the oil and chemicals going into the water, and who is living closest to these hazards?

Historically, even before Harvey, before this storm, before this flood, people of color in Houston bore a disproportionate burden of having to live next to, surrounded by, these very dangerous chemicals. And so you talk about these chemical hotspots, these sacrifice zones. Those are the communities that are people of color.

Houston is the fourth-largest city, but it’s the only city that does not have zoning. And what it has is—communities of color and poor communities have been unofficially zoned as compatible with pollution. And we say that is—we have a name for it. We call that environmental injustice and environmental racism. It is that plain and it’s just that simple.

And so this flood in Houston is exacerbating existing disparities, so that is why I say we have to talk about—when we talk about moving past the flooding part and moving to cleanup and recovery and rebuilding, we have to build in environmental and economic justice into that formula. Otherwise, we will be rebuilding on inequity. We say that’s unacceptable.