Black History

A Family’s Military Legacy

From Buffalo Soldier to Military Physician

By Fern Gillespie

The military changed the life of my cousin Dr. Linda Murakata, MD. When she was age 17, Linda was a teen mother seeking a career to help raise her daughter. She discovered it in the “family business”—the military. After several jobs, she enlisted in the Air Force, where, under the GI Bill, she earned a college degree. Fascinated by the sciences, a colleague at Sherling Plough urged Linda to attend medical school. At age 30, she entered the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey and became a physician specializing in pathology. Throughout her military career, she rose through the ranks: a sergeant in the Air Force and Coast Guard, a lieutenant and commander in the Navy, and she retired as a lieutenant colonel in the US Air Force. For decades, Linda was a pathologist in the Medical Corps at the renowned Walter Reed Medical Complex in Bethesda, Maryland. She analyzed specimens from all over the world and consulted on diagnosis and autopsies. In addition to receiving accolades and honors from the military, in 2000, she received the prestigious NAACP – Roy Wilkins Service Award representing the Navy and in 2010, she was featured in the Aetna African American Calendar for Public Service. Linda is also the Gillespie family genealogist; her mother and my father were siblings. I spoke with Linda for Our Time Press about the legacy of our grandfather Archibald H. Gillespie, who was a Buffalo Soldier and an Army captain during World War I.

When I joined the military in 1972 during the Vietnam War, I started thinking about my family’s military history and about my Granddad, Captain Archibald H. Gillespie, being a Buffalo Soldier, and all of his sons, my uncles, who were in the military during World War II in the 1940s and beyond.

The military tries to instill pride in military history. That’s when I started digging and finding out the entire history of my Granddad in the military. Archibald H. Gillespie joined the military when he was 16 years old in 1898. He had been a laborer, and his family were from North Carolina. In 1899, he was in the 9th Cavalry in Texas. This cavalry was known as the Buffalo Soldiers. The troops traveled around the country by horse. In 1900, he was sent to Fort Apache, and that same year, he was sent to fight in the Philippines War. Until 1905, he was in Washington state, and by 1907, he was sent back to the Philippine islands with the 10th Cavalry.

The Buffalo Soldiers were the 9th and 10th Cavalry. The Cheyenne Native Americans gave these Black soldiers that name out of respect for their fierce fighting in 1867. My grandfather’s whole career was in the Calvary. These Black soldiers were on the horses going from post to post. They moved from fort to fort on horses, not by train or bus. The Buffalo Soldiers did everything on the horse.

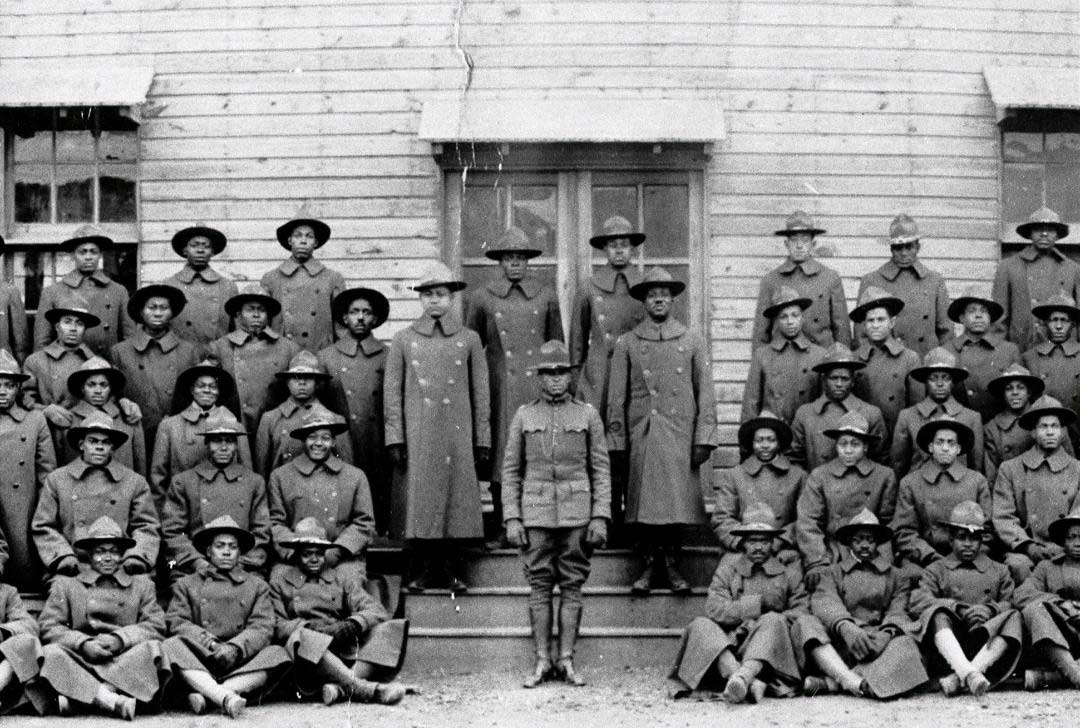

During World War I, the military was segregated. The military wanted to train Black soldiers to be officers to lead the black troops into the war in Europe. So, they recruited and took African Americans out of college, law school, medical school, and also from the enlisted ranks of the cavalry. There were no Black officers back then. So, they had to make Black officers. They sent these men to Iowa and put them into officers training schools so Black officers could lead the Black units in World War I.

So, Grandad, who was a sergeant, and an enlisted soldier for 18 years, was promoted to Captain of Infantry in 1917 to become an officer to lead black soldiers into war. The military didn’t care about the Black soldiers being sent to fight the war who were barely trained. There were a lot of protests about the military sending Black soldiers to the front-line during World War I, and they were just being slaughtered because the young soldiers had no military training. The military was training the white soldiers to use the ammunition and fight warfare.

My grandfather protested. He would not have it that they would send his troops to fight without training. He fought for them to have training. Eventually, he resigned his military commission in protest to make a statement that you can’t send Black troops over to die on the front lines but train white soldiers. He resigned his commission. A few months after my Granddad resigned in protest, the war ended.

After the war, the military assigned my grandfather to West Point Academy to train the white cadets in horsemanship on how to ride horses. He had been a cavalryman. At that time, there were no Black cadets in West Point. When he was at West Point, he wrote to Congressman Hamilton Fish, Jr. of New York. Congressman Fish was aware of Black soldiers during World War I being sent to the front lines to be killed without training. He got Granddad’s rank of Captain of Infantry reinstated in 1932 under President Herbert Hoover. My grandfather finished his military career in West Point. He retired in 1936 and died in 1939. Captain Archibald H. Gillespie is buried at West Point with two of his daughters who died as children.