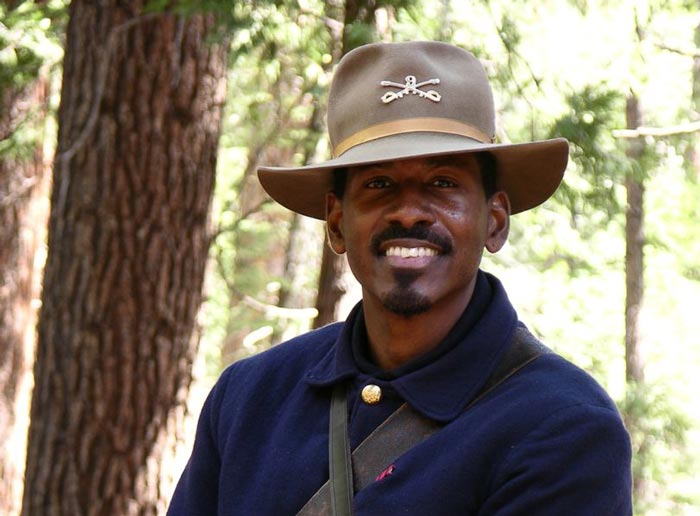

“Gloryland” Book and Author Review By Kurt Repanshek – May 19, 2017

Editor’s note: A general lack of racial diversity across the National Park System has been a growing concern as whites head towards minority status in the United States and worries arise over who will be the coming generations’ advocates for national parks. In Gloryland, Shelton Johnson confronts America’s ugly history with racism head-on in a novel he hopes will encourage blacks to find a connection with the country’s wilderness landscapes. It’s a story, however, that can without too much difficulty be applied to other races, and even to different classes in society.

When I saw that photograph in our research library of the five guys that were on horseback who were part of the 24th infantry — they were mounted but they were part of the infantry — I realized that this was the story. This was the story that I could use as a tool to create a doorway through which African-Americans could pass into the whole idea of national parks, because I realized early on that it had now become an issue of relevance.”

But while he had his story line — “Buffalo Soldiers … is the only history of stewardship of wilderness by African-Americans in the history of the National Park Service,” he points out – Ranger Johnson had another dilemma to overcome. Most members of his audiences — he interprets the Buffalo Soldiers through a monologue presented in Yosemite — were whites. But as he conducted research to strengthen his program, he also was building the resource materials that helped him craft Gloryland, a story that can be read anywhere in the world, not only in a national park.

“Telling the history of one of these soldiers whose parents were probably enslaved, and who basically was functioning as a cavalryman in the Jim Crow South, the same time period as Jim Crow, race became part of the subject because you can’t talk about that time period in America without talking about race because an African-American was being lynched on a daily basis,” Ranger Johnson explains.

All this plays out in Gloryland as Elijah Yancy travels from his boyhood home in Spartanburg — the same town where Ranger Johnson’s father grew up — to Nebraska where he joins the cavalry, and eventually to Yosemite. Along the way the character’s first-person narrative takes the reader to Florida and then to the Philippines so the author can portray the cultural challenges blacks encountered and endured a century ago.

The book’s connection with the spiritualism that can be found in land is not new — indeed, Ranger Johnson makes that point in one of his segments in The National Parks: America’s Best Idea — but in fact is well-seated in history, he notes.

“Where did Moses go for enlightenment? He went up to the mountain top. What was Martin Luther King Jr. talking about, saying he had ‘come down from the mountain.’ This is part of African-American cultural tradition. It’s from the Bible. It’s part of who we are,” explains Ranger Johnson. “And it’s also part of many other traditions as well. Native traditions where people go out to the desert or go out to the mountains to have their fasting, and when they’re out fasting, these visions come to them. So this whole idea of a vision quest, the whole idea of a walkabout among aborigines, these are traditions that go across culture, go across time, and go across continents. And so for me I just made it literal.

“Elijah did go to the mountain top. It’s just that it’s the Sierra Nevada. And so for me, when he was stationed in Yosemite, it was not just a physical posting, it was also a spiritual posting, that being in the presence of mountains can transfigure oneself, can change the way that one looks at the world and how one looks at oneself in the world,” he goes on. “These are these environments that speak to that primary experience of being human on this world, on this planet. Because the thing is that we tend to forget — we’ve spent far more time as indigenous people than as civilized people, and we’ve forgotten that.”

The novel’s thread also, to some extent, mirrors Shelton Johnson’s travel from being raised in inner-city Detroit to a job in Yellowstone and then on to Yosemite.

“I think for every author to some degree there’s a lot of biography that filters into (the story). In literary criticism it’s called biographical fallacy, where you don’t want to assume that what you’re reading pertains specifically to the author,” he says. “But at the same time, your experiences do effect who you’ve become and how you look at the world, and so I took my own journey to Yellowstone, and was transfigured by the experience. Basically, I felt that how could one of these soldiers have an experience of the range of light, the Sierra Nevada, and see Half Dome and see Yosemite Falls and not be transfigured as well, because it’s not a cultural thing in terms of being Euro-American or being Hispanic or being African-American. It’s a human thing to respond to beauty. And so I felt that if it happened to me, it might have happened to one of these soldiers. And that was the jumping off point.”

To be continued