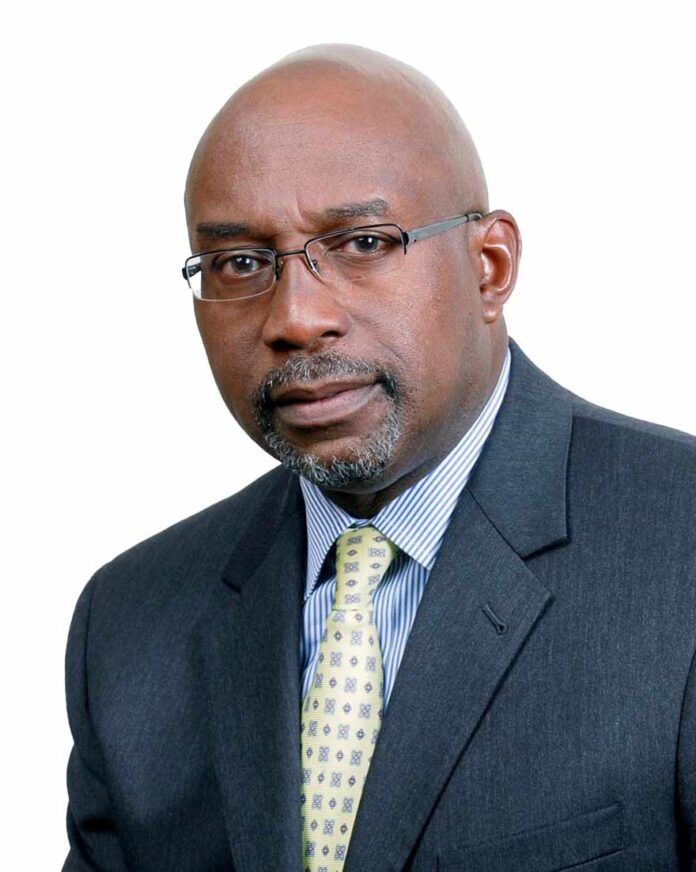

Reflections from a Brooklyn Changemaker

Fern Gillespie

For over 30 years, Colvin W. Grannum has been an influential and instrumental changemaker in Brooklyn’s nonprofits. Currently, the President of Flagstaff Clapham Group, his impact as the founder and CEO of Bridge Street Development Corp and former President and CEO of Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation continues to be felt in the borough’s economic development. Born and raised in Bedford Stuyvesant, Grannum graduated from Erasmus Hall High School. He earned an undergraduate degree from the University of Pennsylvania and a law degree from Georgetown University.

Prior to community service, he was an attorney with the United States Department of Justice, the New York State Attorney General and other institutions. He is on the board of Carver Savings Bank and has served on advisory boards at JP Morgan Chase, Fannie Mae, HSBC Bank, Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Our Time Press recently spoke with him about his continued work impacting community economic development in Brooklyn.

OTP: You are currently the Chair Bed Stuy Early Development Center. What are the organization’s outreach projects?

CG: We have a big campaign to support Black home ownership and we have a big campaign to protect homeowners against deed theft. We help homeowners and home buyers. If you’re a home buyer, we have programs and work in partnership with other organizations, including Bridge Street to help people qualify for mortgages to get the necessary financial education so that they can acquire homes. We also work with existing homeowners who are having difficulty maintaining homeownership.

They could be in foreclosure. They could have confronted some catastrophic event which damaged their home like a flood, or some other natural events. We could help them get more low financing or restructure their mortgages so that they can continue to live there. We have a big campaign in helping people avoid the tax lien sale. Where the city sells tax liens to investors, and investors can use those tax liens to collect all the taxes or to foreclose on a person’s property.

OTP: You are a lifelong Brooklyn resident and community leader. What do you think about the impact of gentrification in some Brooklyn neighborhoods?

CG: I like racial and income diversity in neighborhoods. I think those things are healthy. Growing up on Cambridge Place, we had people with range of different incomes. Not everyone was a professional. We had people with a range of different skills and educational levels. Everybody was Black. I like neighborhoods that have amenities and that are safe. Where I grew up in Clinton Hill is now over 70 percent white.

I wish it was more racially diverse. I don’t think the evolution of the neighborhoods is the problem. I think inequity in income and wealth was the problem. If more Black people could own their own homes and could compete to acquire these homes, I think maybe we would feel differently. Because there wouldn’t be this tsunami of people who are not from our community and some who don’t seem to value our community or its history.

OTP: You headed the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation as Chief Executive Officer from 2001 to 2022. What do you think your impact has been on the legacy of the organization?

CG: I think a lot of people don’t realize there’s a lot of pressure on Black organizations that were founded by Black people. There’s a difference between an organization that was founded by white people and then hires a Black leader and an organization that was founded in a large part by Black folk and consistently led by Black folk. Restoration is one of those places. Bridge Street Development Corporation is another. Just so the pressure on those organizations, in my opinion, is very high.

During the 20 years that I was at Restoration, I saw a lot of organizations just fail. And I don’t think they failed because of poor leadership necessarily. I just think that the pressures on those organizations is extremely high. I think their raising money, getting contracts and getting loans is more difficult. When I got to Restoration, there were some people who wanted it to go into bankruptcy. That was in 2001. We were able to reverse that and keep it going for another 22 to 23 years.

Turning it around and keeping it growing, we simultaneously restored the brand. There was a time when Restoration’s brand was very strong in the in the late 1960s and the 70s while Franklin Thomas was president and in part because it was the largest community development corporation in Brooklyn and owned the most land and had the most talented people and got the most funding.

When I was there, we restored the brand by getting involved with a lot of things like policy. Not so much politics. During my tenure, Restoration became a leading borough-wide provider of financial coaching and counseling. And in connection with Restoration’s 50th anniversary in 2017, we staked out a position as a city-wide leader on closing the racial wealth gap. This was pre-George Floyd.

We invested a significant amount of resources on educating key stakeholders on the racial wealth gap and helping Brooklyn residents begin the process of building savings and wealth. Our team was committed to moving our programs and services beyond the walls of Restoration Plaza.

We sent staff out into the community. We also demolished a major wall–the West Plaza Wall– at the Plaza to make the Plaza more welcoming and interactive with the foot traffic along the Plaza. This was a great success as many more people and organizations set up program, events, and other activities in the West Plaza. We also created a 5000 square state of dance studio that was open to community dance companies and other organizations across the City. I think we made it a business friendly environment. We partnered with local residents.

I think Restoration Rocks and Bed Stuy Alive are an example. We renovated the Billie Holiday Theatre when I was there and had municipal affordable housing. We were committed to partnering with the local merchants and local property owners. The City of New York became a partner in that initiative. We formed that Business Improvement District which is performing today.

OTP: In 1995, you left a successful 17-year career as a corporate and government attorney to be the founding director and CEO of Bridge Street Development Corporation, a faith-based nonprofit. What was your philosophy when you established the organization?

CG: One of the things that I feel good about is when I see Bridge Street’s motto, which is “Building on Community Strength” is that I wrote that back in 1996. That was the philosophy. In Bed Stuy and Central Brooklyn there is strength there. I did not like that when people talked about those communities, many people talked about the weaknesses.

They didn’t emphasize the strength. I’ve always thought that you build on strength. You don’t build on a weakness. So our job as community developers is to identify the strengths of the community and build projects and initiatives and those strengths.