Arts-Theater

Emily Liebowitz Speaks: On Girl Groups, Amiri Baraka, Brooklyn and More

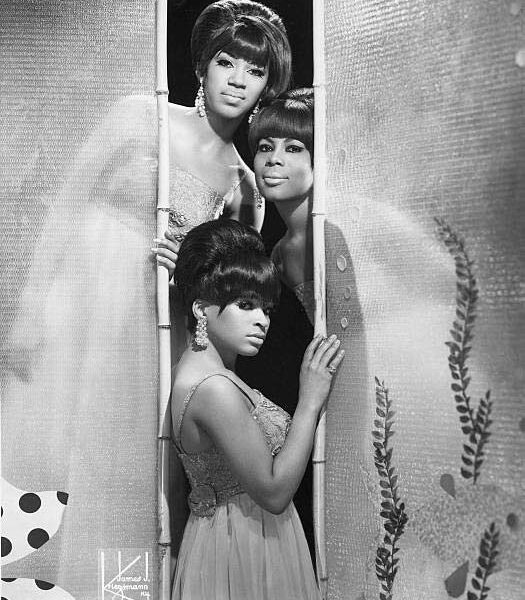

Brooklyn authors Emily Sieu Liebowitz and Laura Flam’s “But Will You Love Me Tomorrow?” released Tuesday has upped the volume on the importance of the dynamic “Girl Groups” of the 1950s-1970s in a music industry shaped, during those times, as “a man’s world.”

The authors talked to 300 participants and observers of one of the most powerful eras in music history where the perspectives of and stories about most powerful artists, including The Shirelles, The Chantels, The Blossoms, The Crystals, The Bobettes, The Ronettes, The Vandellas, The Marvelettes and so many others, have gone unheard.

Recent attention paid to these pioneering African American women artists from books like Will You Love Me Tomorrow? assure that the performers’ legacies as pacesetters, creatives and women of courage will not be erased from American music history. The Girl Groups’ contributions (mostly uncompensated) to the music industry and to the introduction of Black music to a national audience plus what they endured to bring joy and magic with their vocal harmonies to the world — will be remembered beyond tomorrow.

The following Our Time Press’ Q&A with Ms. Liebowitz is the first in a series of interviews on the subject. For more information, on the book, visit: www.hachettebookgroup.com

Bernice Elizabeth Green, OTP:What touches you about the lives of these women from your perspective as an award-winning poet?

Emily Liebowitz, co-author, But Will You Love Me Tomorrow: That’s a good question. Thank you. I loved these songs growing up so much. One thing that’s beautiful about this music is that most of it was written by, and for, older teenagers. I think it was very clear from watching the women perform that this (moment in time) was so significant and watching them perform, you know, they respected their fans. They also respected that time in their lives, but it was clear through the interviews, they lived other lives. Now, they are older. They still perform. There’s a gravitas. It is just as powerful to see these songs sung by women who had lived full lives and are emanating from that place as it probably was watching them on stage during their teenage years. I’m in my late 30s. That’s really powerful example for me that women need not displace their own lives by putting emphasis on one thing — even as big as (that experience) was to each of them. So I think that drew me to them even more.

The book is titled after the song, “But Will You Love Me Tomorrow?” Why?

EL: We named the book after the song because it is probably the biggest hit of the Girl-Group era. It shifted the place of the girl groups and pop culture. The lyrics themselves were actually written by Jerry Goffin, which many would be surprised to know because the music is infused with a kind of life fantasy of what it’s like to be a woman. There’s that kind of projection of a projection, centered around self-fulfillment. But Will You Love Me Tomorrow? is a song about the present that is so palpable and, yet, thinks about the future in the same way as the music keeps us so present there’s this kind of excitement about what the future holds. At the time, it was probably somewhat fearful to have young women speak in that way. As we grow, we know how vulnerable we were when we were young in a way that we can’t see when we’re young. I speak from being that kid and experiencing those complicated emotions that we all feel to a certain extent: fear and surrender. There’s something very special about it. The lyrics of the girl group songs are taken very seriously, you know. The young take their emotions very seriously, and those emotions can be very extreme. But to them, it’s “how do I say it in words?”

You go with your feelings so much more when you’re a teenager and, given the weight today’s technological world can bring. can be very extreme. For a teenager it is “How do I say what I mean?” You’re going with your feelings so much more when you’re a teenager. I think it’s very special when one can use emotions as a kind of thought. Even if that thought is like a little bit of fear. “But Will You Love Me Tomorrow?” places you at the precipitous of something bigger than yourself.

On the other hand, there is the Marvelettes singing Please, Mr. Postman, an ode to not an icon or idol but a local guy.

I have a great affection lyrically for Mr. Postman, and I’ve loved the song fiercely my whole life. The lyrics are the epigraph, in fact, to my first poetry book. I love that it places us all in the time when we were communicating with each other, and not through technology. So even if you are not from that time of dependence on the Postal Service, you hear these songs and you are immediately shifted to that time of dependence on the postal service to deliver the messages. But you also know it implies a sense of community. As a kid, you knew the postman. You talked to the postman.

Before the Girl Groups came along with their songs — written for them or by them — on the national front, the idols were not the messengers, not the postmen.

E.L. Young women were idolizing, what idols were thrown at us like, say, Frank Sinatra. Then you have this song that comes out and that’s real-world about having a crush and waiting on the postman and it’s like, “Yeahhh!” I love Georgia Dobbins. She wrote the lyrics to that song. She was one of the original Marvelettes but only for like a day and a half because her dad didn’t understand Motown.

I think we do look to these songs that carry a certain kind of nostalgia.

There’s another Marvellettes song that does that brings on that feeling, that sense of transmuting to a time past: Beechwood 4- 5789. In the title alone you know you have to figure out what a party line is like, and the idea that you could listen in on other people’s calls way back then. There are all these things built into that song that’s really interesting you know but when we think about the old groups, it’s about a time of change and of a major shift. Not only can the music bring you back there but I think it helps us as adults honor that part of our lives.

These songs can do a lot that poetry can’t and you know that’s hard for me to say because I love poetry very much but I think that it’s complicated. We divide a creative act into parts to be commodified like a song that’s successful. Unfortunately, the women of those groups were locked out of that success.

The lyrics themselves were about a time of change and of a major shift. Not only can the music bring you back there, but I think it helps us as adults honor that part of our lives.

Why can the Girls Group songs be redefined as poetry?

E.L.: As far as poetic achievement, at its core of course I would argue that the Girl Groups music is absolutely poetry.

What was the first thing in your plan for this book?

E.L.:Research.

I had to figure out how the girl groups were talked about, how this music is talked about, and what people actually meant when they’re using the words they’re using.

A book that really helped me with this project was written by one of my favorite poets. It was Amiri Baraka’s Blues People. Having a poet’s view of talking about how this music developed and a Black person’s view also of how this music got corrupted or mixed with or created, continues. Essentially music today came from what was right, but it was really helpful to see someone talking about that from these really entrenched difficult social situations that weren’t clear cut. One thing Amiri Baraka said that really struck me right away was he felt that Black women always worked so his words changed what I understood of the history of labor in this country and how so many young girls were putting so much into it after the Civil War. The work that was available to young girls was domestic work and I hadn’t thought about that. Now I see the devaluing of their work and their lives.

Learning about those connections really helped me understand what we’re talking about when we’re talking about these kinds of surface things. I had to get the lay of the land, so I read a lot about early rock and roll music and how it was being recorded, how it got to where it did, and who was involved and who was not involved in what was happening.

As I said, I learned a lot from Amiri Baraka. He was one of my biggest poets and inspirations when I was in college.

Is there anything you would like to say to the women of those Girls Groups?

E.L. I am grateful for their music and their courage to use their voices at such a young age to perform and to live publicly, however that played out, was very brave.

I’m so grateful for the time they took to teach us about their lives and souls. Just sharing their gifts changed my emotional capacity and my ability to talk about it and share my own inner reality.

I hope they’re able to take in how much they’ve given. That I get to talk about the music and what they did is a true honor. I know Laura feels the same way — so lucky to have been in the right place at the right time to work on this book and hopefully there will be more.

Emily Sieu Liebowitz is the author of National Park (2018) and the recipient of fellowships from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Vermont Studio Center, and Wendy’s Subway. Her writing can be found in The Brooklyn Rail, Poets & Writers, Poetry Magazine, and other publications. Liebowitz splits her time between Brooklyn, NY, and her hometown of Hayward, CA.