By Fern Gillespie

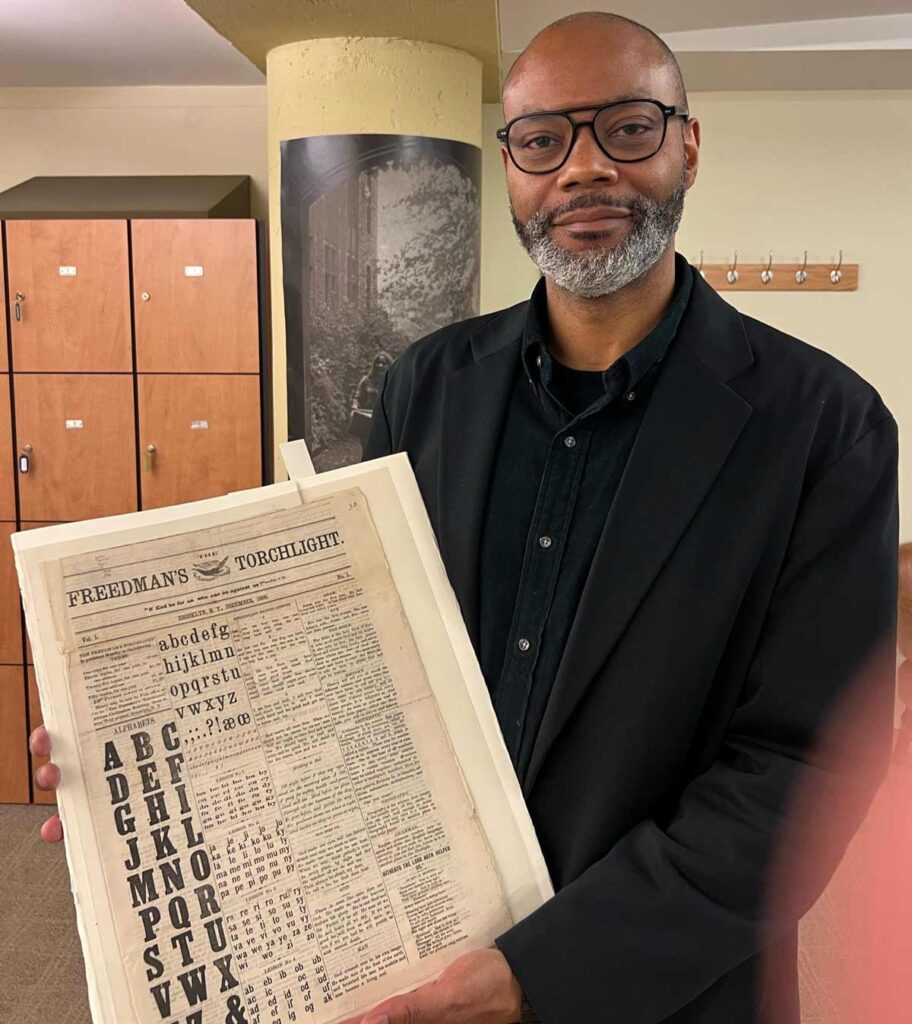

When Dr. Raymond Codrington, President and CEO of Weeksville Heritage Center, was invited by Trinity College to view a rare 1866 first edition of Weeksville’s Freedman’s Torchlight newspaper, he was thrilled.

“It gave me goosebumps to see the original because when you go to Weeksville, we have we have these big banners that are six and seven foot high that have excerpts from the newspaper,” said Dr. Codrington, who holds a doctorate in cultural anthropology from CUNY. “Freedman’s Torchlight is a large 1866 broadsheet. So, when you look at it and hold it, I can imagine the effort it took to get this printed. The thought that it took to come up with the content. When I stood there and held the document, it gave me the chills.”

Published in Brooklyn’s Weeksville community at the African Civilization Building, the Freedman’s Torchlight was not a traditional newspaper. It was published after the Civil War when emancipated Black Americans, who had been banned from reading, were moving into Weeksville, which was established in 1838 by freemen. ln addition to news, it was a teaching tool. The front page of the Freedman’s Torchlight has oversized fonts of the alphabet, numbers and information on vocabulary, grammar, geography, religion and arithmetic.

“Some people consider it a newspaper. Some people considered it a textbook. It goes between giving information and giving the alphabet. It encouraged people to read,” said Dr. Codrington. “There is a respectability politics of how to comport yourself as a man of respectability in public. It served several different purposes. Most importantly, it’s an artifact and a document of the time period.”

The Freedman’s Torchlight, the first Black newspaper in New York City, was donated to Trinity College by a collector. “Trinity College is doing a fine job of being stewards of this document,” he said. “It’s an incredible piece of history.”

“I always think of Weeksville as a teaching place, a learning place, an intellectual place for free Black people to come and really learn more about themselves and other Black folks. To become politicized on slavery and abolition,” he said. “Documents like Freedman’s Torchlight are just incredible parts of Weeksville history.

It’s the story of resistance to what could be done under the harshest circumstances. All this was done 11 years after the abolition of slavery in New York State.”

Located in Crown Heights, Weeksville retains historic houses from the 1860s, 1900, and 1930s to the contemporary education center built in 2014. “The designers brought the contemporary and historical together,” he said. “To be centrally located in the neighborhood is really unique.”

Weeksville has a popular interactive dialogue tour for school children. They learn that the historic Black community had schools, churches, stores, a newspaper, and even a sports team. “We are competing with the Xbox, virtual reality, and all that, but when you come to Weeksville, it’s a different kind of experience,” said Dr. Codrington.

“Black children get it. They ask questions about what it was like to live as a child back in historic Weeksville. They understand how difficult it would’ve been as a child and as an adult to live in that time in post-slavery, in the late 19th century and the early 20th century.”

This year, the New York public schools will be incorporating Black History in the curriculum. “It’s especially timely, given the fact that other parts of the country are taking the reverse course and not teaching Black History or teaching it in a very revisionist way,” said Dr. Codrington. “So, I think the opportunity to teach Black History in an authentic way to our young people is incredible.”

An important part of the history of Weeksville is Joan Maynard, who established it as a historical institution in the 1960s. “Joan Maynard was incredible. Without her and a number of dedicated individuals from young people to adults, Weeksville would not be here,” he said. “Joan Maynard had the vision around historical and cultural preservation about saving his houses and telling the story of Weeksville.”

Dr. Codrington’s interest in cultural anthropology stems from his experience growing up in the African diaspora. His parents immigrated from Jamaica to England, where he was born. As a child, his mother moved the family to Texas. “I think my skills are well-suited. In terms of seeing things moralistically and making connections between social, economic and political forces,” he said. “Also, understanding and acknowledging the significance of culture and how people adapt to hard circumstances and build their own institutions.”

Upcoming events include yoga, Weeksville Green Farmers Market, a major art exhibition, Forward Ever—Celebrating Where We At Black Women Artists (1971-Now), and In Pursuit of Freedom, a multimedia theatre experience.

“My interest in museums, collections, history, and public engagement all came together in Weeksville,” said Dr. Codrington. “It has the spirit of all the people that had lived in Weeksville. There’s the energy and history of the elders who built and lived in Weeksville. Going into the houses, you can feel it.”